-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

How long can Liz Truss hold on?

How much trouble is Liz Truss in? Just six weeks into her premiership, the Prime Minister’s economic plans are in tatters after she axed her chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng, reversed on her campaign pledge to scrap the scheduled corporation tax hike and brought in Jeremy Hunt as his successor. Now Hunt is calling the shots on the economy and he plans to reverse much of what the Truss government have announced so far, with tax rises and public spending cuts to come. Truss’s own supporters are privately asking what the point of her government is now.

Unsurprisingly, this has all led to talk among Tory MPs that the end is nigh. One Tory MP, Crispin Blunt, has come out publicly to call for Truss to go. The mood in the party soured last week after Truss’s difficult 1922 committee appearance and her painful press conference on Friday where she refused to offer an apology or engage with questions on why Kwarteng had been sacked. The papers are filled with apocalyptic source quotes predicting Truss’s imminent demise, while various potential successors are being talked up: from Ben Wallace as a great unifier to Rishi Sunak as the best placed candidate to calm the markets.

In the case of both Theresa May and Boris Johnson, MPs took their time

So, how realistic is the idea that Truss could be forced out within days or weeks? ‘It seems over,’ says a former minister. ‘Nothing can be worse than this.’ Other MPs say they believe a lot of letters of no confidence have already gone in and think there could be an attempt to oust her within a fortnight. Technically Truss is safe for a year – but a high number of letters could lead the 1922 committee to consider changing the rules.

What helps Truss is that there is no common consensus on who would be best placed to take over. In the past, MPs have held off on regicide by fearing the successor. ‘Changing leader is unrealistic,’ says a minister. It’s also the case that Downing Street plan to dig in. Jeremy Hunt’s appointment as Chancellor is intended to ease the concerns of MPs on the left of the party, thereby shoring up Truss’s position.

There are also plenty of Tory MPs who are very unhappy with the leadership and believe it could be terminal who still say it’s too early to move. Instead, they argue Truss is in last chance saloon. Rob Halfon has said Truss still has an opportunity to change tack and survive if she moves fast. Matt Hancock has suggested the answer is a reshuffle bringing in all the talent (no word on whether that includes the former health secretary). Meanwhile, on the right of the party, Christopher Chope has expressed his dissatisfaction that Truss U-turned on tax cuts – but said he still backs her: ‘I’m more confident that if we gave the Prime Minister our support, then she’d be back on track’.

In the case of both Theresa May and Boris Johnson, MPs took their time between the leader’s loss of authority and pushing them out. The danger for Truss is that a combination of bad polling, economic uncertainty and a lack of parliamentary support means that MPs conclude the situation is unsustainable and act now, worrying about what comes next after.

Jeremy Hunt is the ‘unity’ leader the Tories need

Liz Truss is now prime minister in name only: Jeremy Hunt, her chancellor of the exchequer, now holds power. He has repudiated her tax-cutting mini-Budget in a round of media appearances – his performances being far more convincing than Truss’s graceless eight-minute press conference on Friday. His admission that spending cuts will be needed and that ‘some taxes are going to go up’ to balance the books has injected a much-needed dose of realism.

The question on everyone’s lips is: what will Hunt do now? Is he a stalking horse for a new PM (Rishi Sunak being the obvious candidate) or is the former head boy at Charterhouse himself a prime minister-in-waiting?

Let’s look at the options. Even a deeply divided Tory party should be able to see that the Truss project – whether you liked or hated it – is now dead in the water. But they need to pull together around something. Can Tory MPs bury their differences and rally around a unity candidate? The job would be to see the country through the market squalls into a general election, possibly as early as next year.

Hunt is an obvious choice, given that he has already started the repair work. He is now working on a medium-term financial strategy at the Treasury and operating in tandem with Andrew Bailey, Governor of the Bank of England, to make the numbers add up to the satisfaction of a newly-empowered Office of Budget Responsibility.

Hunt is a man who cares about the national interest, but he is not lacking in ambition

Each of these institutions – the Bank, the Treasury and the OBR – were treated with disdain by Truss and Kwarteng. Indeed, the disagreement between Bailey and Kwarteng over who was responsible for ructions in the bond market and the knock-on impact on pension funds may well have settled the latter’s fate.

The Bank was sensitive to Tory criticism that it had been too timid in raising interest rates – it blamed the abrupt increase in gilt yields on the government’s mini-Budget. But Kwarteng and Truss (aided and abetted by Jacob Rees-Mogg) disagreed. The row did a fair bit to undermine investor confidence in the stewardship of the UK economy.

Jeremy Hunt is the proverbial safe pair of hands. He ran as the self-styled ‘sensible candidate’ in the 2019 leadership race to succeed Theresa May but his Remain credentials did for him in the end – and he lost decisively to Boris Johnson. Now he is both in office and in power. He wouldn’t ever have agreed to take on the chancellorship (the most thankless job in government) without extracting terms. He will have insisted on picking his own team, and on being given a free hand to reverse the brief, ill-fated Truss-Kwarteng trickle-down economics experiment.

The cabinet ousted Boris Johnson, but don’t expect the cabinet to depose Liz Truss, who picked her ministers based on fealty to her rather than competence. So everything comes down to the parliamentary party. Crispin Blunt has today become the first backbencher to call for her to go but there have so far been no others. The 1922 committee no longer enjoys its fearsome reputation, irrespective of what you may make of Sir Graham Brady (who is returning from holiday in Greece this weekend).

MPs will be moved by two factors: the financial markets (which are pushing up the cost of borrowing) and the polls which currently show a 27-point Labour party lead.

Sir Roger Gale, the perennial Tory party rebel in recent years, told LBC that a period of calm under Truss-Hunt leadership may save her – at least in the short term. This may well be wishful thinking.

Hunt is a man who cares about the national interest, but he is not lacking in ambition. Sunak has been proved right about ‘fairy tale economics’ but having moved against Johnson, he may worry about wielding the knife again – or standing and losing again. This offers an opening to Hunt (assuming there is no deal between the two men).

During the 2019 leadership election campaign, I had breakfast with Hunt (then foreign secretary) at the Corinthia hotel. He arrived with a Union Jack badge in his left lapel and not a hair out of place. At the time, sensing he was losing to Johnson, Hunt told me that ‘being boring and technocratic does not work’.

Well, boring does it for me. And, I suspect, for much of the rest of the country. So hold on Sir Keir Starmer: Jeremy Hunt’s time might just have come.

Watch: first Tory MP calls for Truss to go

In office, Liz Truss promised to be the ‘disruptor in chief’. Unfortunately, most of that disruption has proved to be in the markets and the polls as her short-lived revolution tanked the standing of both her currency and her party. With Labour and mortgage rates on the rise, Truss’s authority has disappeared within days. She’s been forced to ditch her ideological soulmate Kwasi Kwarteng for Jeremy Hunt, the embodiment of Tory orthodoxy, and is now very much a prisoner of her party as they try to find someone – anyone – who can dig them out of their self-inflicted mess.

Most of these discussions are happening behind closed doors as MPs weigh up their various options: a coronation or a contest? Ben or Boris? A fresh face or old? But this afternoon one Tory MP has at last opted to break cover and call for Liz Truss’s resignation: Crispin Blunt, the onetime prisons minister last seen attempting to defend disgraced jailbird Imran Ahmad Khan. Blunt by name, and by nature, the Reigate MP chose the comforts of the Andrew Neil Show to declare that ‘The game is up’ for Truss, adding that if his colleagues agree ‘that we have to have a change, then it will be effected’ though ‘exactly how it’s done and exactly under what mechanism’ is not yet clear.

How many of Blunt’s colleagues will follow suit? Mr S will be keeping track on Coffee House so watch this space…

Sunday shows round-up: Is Truss a ‘libertarian jihadist’?

Jeremy Hunt – ‘The Prime Minister is in charge’

To say things do not look rosy for Liz Truss would be quite the understatement. With the government now on its second Chancellor in as many months, and its once flagship policies being hastily swept under the carpet, the Conservative party appears to be in damage limitation mode. Laura Kuenssberg spoke to the new Chancellor this morning, in a pre-recorded interview, asking him if Truss was now such a damaged figure that he was the one really calling the shots:

‘There is a very difficult job to be done right now’

Hunt told Kuenssberg that he would be looking at all government departments’ ‘efficiencies’ and refused to rule out ditching more measures from September’s mini-Budget. He added that ‘some taxes will go up’ to help smooth over the recent economic turbulence:

Robert Halfon – The government has looked like ‘libertarian jihadists’

Sophy Ridge spoke to the chair of the Commons Education Committee, Robert Halfon. Halfon argued that the government had lost public faith because it was straying too far from compassionate conservatism:

No. 10 remarks about Javid ‘disgusting’

Ridge also bought up remarks reportedly made by the Prime Minister about the former Chancellor Sajid Javid:

Matt Hancock – Truss should reshuffle her cabinet

The former Health Secretary Matt Hancock made up one member of Laura Kuenssberg’s political panel. She asked him what he thought the Prime Minister’s next steps should be:

BioNTech team – ‘Changing cancer patients’ lives is in our grasp’

And finally, Kuenssberg spoke to Uğur Şahin and Özlem Türeci, the co-founders of BioNTech, the company made famous by the Covid vaccine which they developed alongside Pfizer. The pair spoke about a potential breakthrough in using vaccinations to fight against cancer:

Hunt on Truss: ‘She’s willing to change’

Liz Truss’s gaoler has just done another BBC interview. Jeremy Hunt continued to try and give himself maximum room for manoeuvre, saying ‘I’m not taking anything off the table’. He repeated his message:

We are going to have to take some very difficult decisions both on spending and on tax. Spending is not going to increase by as much as people hoped, and indeed we’re going to have to ask all government departments to find more efficiencies than they’d planned. And taxes are not going to go down as quickly as people thought, and some taxes are going to go up.

It will be fascinating to see if Truss is as direct on this when she is asked the question at PMQs next week.

The abacus is back

Hunt also pledged that the Halloween fiscal statement would be ‘a bit like a Budget’ and that the government would ‘properly account for every penny.’ On the OBR’s assessments, he said ‘we’ve been honest that it was a mistake not to do that in the mini-Budget before.’

The abacus is back. He set the government the test of minimising the rise in interest rates: remember the Bank of England monetary policy committee meets on 3 November to set interest rates. The market still expects big rate rises, from 2.25 per cent now to 4.25 per cent by Christmas.

On Truss, Hunt insisted ‘she’s listened, she’s changed’. He maintained that she was still in charge, but that the government’s mission had been delayed, not stopped:

She has changed the way we’re going to get there. She hasn’t changed the destination, which is to get the country growing. I think she’s right to recognise, in the international situation and the market situation, that change was necessary. But change absolutely determined to deliver that economic growth that’s going to bring more prosperity to ordinary families up and down the country.

When asked about his own prospects, Hunt said he wanted to show that he was an ‘honest Chancellor’. He also said of his own leadership ambitions:

I think having run two leadership campaigns and having, by the way, failed in both of them, the desire to be leader has been clinically excised from me.

Seal of approval: Over in Washington this weekend, Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey said of Hunt that there had been an ‘immediate meeting of minds on the importance of stability and sustainability.’ But, in what will be seen as a hint of more interest rate pain to come, Bailey suggested a ‘stronger response’ might be needed to combat inflation. Reuters has more.

Does Joe Biden know what ‘super-wealthy’ Americans pay in tax?

Joe Biden, ice cream in hand as so often, yesterday pronounced on Liz Truss’s tax reform disaster.

‘I wasn’t the only one that thought it was a mistake,’ said Joe Biden, sounding every bit the wise old man of global politics. ‘I think that the idea of cutting taxes on the super-wealthy at a time when… I disagree with the policy, but that’s up to Great Britain.’

That concession at the end is the President realising he’s just breached the normal rules of diplomacy – by giving his opinion on an ally’s domestic difficulties. But he just can’t help himself.

Biden has probably forgotten, but he has proposed increasing the top rate of marginal tax in the US

Steerpike wonders, however, if Biden – no pauper himself after cashing in on his status after the Obama years – can recall what the highest rate of income tax in the United States is.

Because Liz Truss’s proposal, if it had been allowed, would still have left Britain a considerably less accommodating fiscal destination for the super wealthy than America currently is.

Let’s explain it, nice and clear for dear old Joe. Liz Truss had proposed reducing the highest rate of income tax – on people earning £150,000 or more per year – from 45 per cent to 40 per cent. In the US, at the federal level, the highest rate of income tax comes in at 37 per cent for those earning $523,600 (about £470,000 at current exchange rates). Someone earning the equivalent £150,000 in America would only narrowly creep into the third highest federal tax bracket of 32 per cent. If they managed to shed $4k from their income liability, they would pay just 24 per cent.

Yes, Americans face more state-level and property taxes – but only three states have a personal income tax rate above 10 per cent. Most states charge far less. Someone earning $550,000 a year in Wyoming, for instance, would pay about 33 per cent in tax.

So – not only are there many more ‘super wealthy’ Americans – they pay considerably less as a percentage of their income in tax than their well-off British peers. It’s not very fashionable to say so, but Steerpike can’t help wondering if those two points are connected.

Biden has probably forgotten, but he has proposed increasing the top rate of marginal tax in the US – for those earning over $530k, remember – to 39 per cent. That would still leave the US federal rate below where Liz Truss was proposing it should be for the UK.

Perhaps he should reflect less on Britain’s fiscal rates and more on the failure of his absurdly named Inflation Reduction Act and the threat facing his party in the upcoming mid-terms – as less fortunate Americans struggle to cope with the cost of living.

Who voted for Jeremy Hunt to run Britain?

Jeremy Hunt has no mandate to lead Britain. He couldn’t muster sufficient Tory MPs behind him to properly enter the last leadership contest. He was beaten overwhelmingly in the one before that.

He was a key part of the failed Theresa May administration that lost a parliamentary majority at a general election. He played no role in the Boris Johnson administration that won it back with plenty to spare (a victory from which the Conservative mandate to govern still flows).

Yet in a round of interviews this weekend, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer simply ripped up the economic agenda of Liz Truss. He mocked and then buried the PM’s vision of dynamic unfunded tax cuts. He pulled the rug from under her Commons pledge that the Government will not cut public expenditure. And Hunt made clear that he, rather than she, will decide on such matters as whether to stick with a promised reduction in the basic rate of income tax.

He was only in post because of mistakes that had been made, he added. All he would say in defence of his nominal boss was that she had won the Tory leadership contest ‘fair and square’ and therefore could not respectably be removed from 10 Downing Street absent a general election. Yet he did not even bother to pretend that the economic strategy he intends to impose requires her consent, let alone her active support.

We have clearly entered an era of Tuscan turnover in the Palace of Westminster

Perhaps the calculation is that, given sufficient humiliation, even such an extreme case study of the Dunning-Kruger effect as Liz Truss has turned out to be, will realise that her reputation is being further depleted rather than enhanced by every extra day she chooses to cling on.

It is facile to complain that Truss is an altogether blameless victim of a shadowy financial establishment which holds illegitimate primacy over democratic outcomes. For a start, her own mandates are narrow and fragile: from her constituents in 2019 to be the MP for South West Norfolk and from 58 per cent of the Tory grassroots electorate to be their party leader. It has never been the popular will that she should be prime minister: that post depends on the consent of her parliamentary colleagues.

More pertinently still, private citizens and private concerns are not under any compulsion to lend their money to a government; and if they decide an administration is not a good bet they will naturally charge more to do so. If the administration in question cannot afford the bills then it must borrow and spend less or tax more. If it has promised not to do so then its authority will be shattered. These are basic laws of political gravity. Regimes which seek to defy them always come a cropper. No conspiracy required. So one should not weep for Truss.

But a few tears for the overall standing of British democracy would certainly be in order.

The takeover of the levers of power by Hunt, who supported the defeated Rishi Sunak in the latter stages of the recent leadership race, certainly has echoes of the old Tory ‘magic circle’ method of selecting a head honcho. He may not have the air of the grouse moor about him, as was said about Alec Douglas-Home, but the patina of the standard issue Home Counties Cameronian centrist is unmistakable.

On Friday, Nigel Farage claimed to have it on good authority that Hunt was returning from a mysterious trip to Brussels when he was confirmed as the new chancellor and mischievously asked in a tweet: ‘Had he taken any instructions?’

Lately, comparisons between UK politics and its traditionally chaotic Italian counterpart have been all the rage. We have clearly entered an era of Tuscan turnover in the Palace of Westminster. Or maybe that should be Sicilian snakes and Lazio ladders.

In which case it is hard not to see Hunt as our version of the former European Central Bank boss Mario Draghi, who was called in by Italy’s president to form a technocratic government after the collapse of a previous regime.

He’s on his way out now – getting replaced by a populist right-winger after the Italian electorate were allowed a say on the future direction of their country via a general election.

It is getting harder and harder to dispute that a fresh popular mandate to determine who should govern is needed here as well, less than three years after we last went to the polls. Brenda from Bristol will not be pleased, but another early general election is starting to feel inevitable.

Ben Wallace: If defence spending pledge goes, so do I

In politics, where there’s death, there’s life. And as Liz Truss’s premiership crumbles before our eyes, all attention in SW1 is which lucky legislator gets to replace her. Second time Sunak? The people’s Penny? Back again Boris? Or perhaps the man who many wanted to run this summer but ended up dropping out: Ben Wallace, the popular Defence Secretary.

The former Scots Guards officer has been a long-standing fixture at the top of the ConservativeHome Cabinet rankings but opted to back Liz Truss in July rather than run himself. Instead, he extracted a pledge from the Trussette to raise defence spending to 3 per cent of GDP by 2030 – a pledge that appears to be in danger after Jeremy Hunt’s media round this morning.

Now, with Truss’s unhappy interregnum drawing towards its close, could the Flasheart of the Forces mount a bid himself? For the Mail on Sunday – the voice of Middle England – reports that friends of Wallace are saying he is ‘rethinking’ his objections to running for leader. One chatty chum of Wallace tells the paper:

Ben is concerned that the economic problems mean that the Prime Minister could U-turn over her pledge to increase defence spending to 3 per cent of GDP by 2030. He is very concerned that we could be on the brink of a global war, and wants to make sure that we are well-protected as a country.

The ally pitches Wallace as that rarity in British politics: a unity candidate who can bring the hopelessly divided Tories together in a way others can’t. Mr S is a fan of Wallace’s talents, but can’t help but wonder what has shifted so suddenly in his fortunes now. Is the Defence Secretary actually making a run? Or is it more about maneuvering to keep that 3 per cent commitment alive and well?

Kwarteng’s allies pin the blame on Truss

Kwasi Kwarteng’s letter to Liz Truss was outwardly loyal. But he made it quite clear he had been sacked for trying to implement her ‘vision’.

Friends of the former Chancellor are now suggesting that it was the Prime Minister who was the moving force behind the mini-Budget’s most disastrous measure: the abolition of the 45p rate. They tell the Mail on Sunday that he had proposed not including it, only for Truss to reply – ‘let’s go for it.’

One wonders how many more of these inconvenient details might leak out in the coming days. The problem for Kwarteng and Truss, though, is that they are neighbours in Greenwich as well as Downing Street. Things could be a bit chilly on the Cutty Sark if Truss ends up moving back anytime soon.

The plot to put Rishi Sunak in No. 10

When Rishi Sunak resigned over Boris Johnson’s leadership, he acknowledged that it might be the end of his political career. His dreams of leading the Tory party already seemed over, thanks to his wealthy wife’s non-dom status. In a few short weeks, the Tory party did something quite extraordinary, and forgot about all that. Setting aside what would normally have been a career ending scandal, they very nearly made him prime minister. Now his supporters are trying to engineer something even more amazing: ousting the woman who beat him in the party leadership contest, and installing their man in No. 10.

The first step of their plan involves market turmoil on Monday morning. Sunak and his supporters hope that more financial panic will be enough to force Truss to quit – whether voluntarily; or via a threatened change in the party rule book that theoretically protects her for a year; or via some other mechanism they have yet to come up with.

As she sacked her Chancellor on Friday, Truss brazenly told him that he must be sacrificed to save her skin

Step two involves the coronation of King Rishi, the argument being that he is the only figure that can at least semi unite a furious and fractured parliamentary party. Jeremy Hunt may fancy his own chances, but is unacceptable to many MPs who backed Sunak. The idea is to keep him where he is – in No. 11 – while offering the other big Tory party leadership contest loser – Penny Mordaunt – another of the great offices of state (Foreign Secretary).

Step three involves convincing a mutinous parliamentary party that this new set up is better than the alternative: Truss/Hunt attempting to play political Siamese twins, when he has just publicly junked her entire economic agenda and she is Prino: prime minister in name only. Nobody really believes this macabre charade can last long.

Step four is something all sides can agree on: resolving to do whatever it takes to avoid a general election. Sunak’s outriders – already busily working the phones – will argue that their proposed solution restores some political stability, deferring the terrible day of reckoning that looms at the polls. Two years is an eternity in politics, they argue – perhaps in the interim, something will come up?

As she sacked her Chancellor on Friday, Truss brazenly told him that he must be sacrificed to save her skin.

‘They’re coming for me,’ she said, or words to that effect.

It was a terrible miscalculation. Nobody believes her position is now anything other than more perilous. Those closest to her also admit the obvious: the small state; low tax; high growth vision that won her the party leadership – shared by so many Conservative party supporters – is now dead, perhaps for a generation.

Whether it’s Hunt or Sunak in No.10 doesn’t really matter. The high tax and spend Remain-leaning Establishment blob has won.

The misconception about Putin’s big red nuclear button

There is a common misconception that the leaders of nuclear states have a ‘red button’ that can unleash Armageddon. As Vladimir Putin continues to hint at the use of non-strategic (‘tactical’) nuclear weapons in Ukraine, there is some comfort in the knowledge that it is not so easy.

Ironically, launching the kind of strategic nuclear missiles whose use would likely spiral into global destruction is somewhat easier than deploying the smaller weapons which – however vastly unlikely – could conceivably be used in Ukraine. These lower-yield warheads would need to be reconditioned in one of the 12 ‘Object S’ arsenals across Russia holding them, and then transported to one of 34 ‘base-level storage depots’. From there they would need to be loaded onto a bomber or mated onto a suitable other delivery system.

Were Putin somehow to go full Dr Strangelove, there are many other human beings in the chain of command

Given that Russia has not even used them since 1990, no one knows for sure what state they would be in, and likely no one still in service has any practical experience. There would presumably be a group of wary engineers gingerly thumbing their way through faded instruction manuals long before Putin could even give a fire order.

If he ever did, though, the process is mercifully much more complex that simply mashing a button in a moment of pique. Like his US counterpart, Putin is accompanied everywhere by an aide carrying the ‘nuclear briefcase’. Called the Cheget, this actually contains special communications gear that is used to issue and authenticate the president’s orders relating to a nuclear launch.

The defence minister and chief of the general staff have their own Chegets, which connect to the Kazbek nuclear command and control network. Were Putin so minded, his aide would activate his Cheget, and he would issue an encrypted launch command, which would be transmitted to them. Although there are protocols to deal with the theoretical possibility that both were out of action, such as if there had already been some decapitating strike against the High Command, generally at least one of the other two would need to validate the command.

Then, the approved order goes to the General Staff, which issues authorisation codes and targeting details. This would usually happen through the Strategic Rocket Forces’ command bunker at Kuntsevo, west of Moscow, or else the backup one at Kosvirsky in the Ural Mountains.

Again, in extremis, the command staff in the bunkers could launch without the command codes, had the General Staff also been eliminated. Backup sets of launch codes are kept in each bunker, along with a special sledgehammer made precisely to be able to break into their highly-secure safes. Either way, only then would the targeting details and authorisations be transmitted by encrypted digital links to whichever unit was actually meant to launch the attack, whether the crew of a bomber, submarine or missile silo, or the gunners of a 203mm 2S3 Pion field artillery piece capable of firing a nuclear shell.

This may all sound rather cumbersome. It is, and deliberately so, both to make absolutely sure that any commands really have come from the president, and to introduce some friction and delay into the process. After all, if the political and military leadership have all been taken out, there is still something called the Perimeter system, a ‘dead hand’ backup system that allows the General Staff to launch land-based missiles directly in case of confirmed enemy attack.

What this also means is that were Putin somehow to go full Dr Strangelove, there are many other human beings in the chain of command. The defence minister and chief of the general staff could refuse to authenticate the order. However, they might authenticate it, or Putin could appeal directly to the General Staff. Nevertheless, while he may have the legal authority to launch nuclear weapons, the officers in question may cavil, delay or consider whether his decision conforms to official doctrine. This, after all, sees their use strictly reserved for cases where the Motherland is under direct, existential threat.

Of course, this could be considered mutiny, even treason, and the consequences could be serious. But so too are the likely outcomes of breaking the nuclear taboo. We do not know whether anyone would be willing to refuse such an order – but nor does Putin. One of the secrets of command is never to give an order likely to be disobeyed. For Putin, it would be the beginning of the end, and he must know it.

However brutal Putin’s regime may be, this is not Stalinism. Although the Federal Security Service’s Military Counterintelligence Directorate is more concerned with watching the generals than hunting foreign spies, there are no hard-eyed political commissars waiting to put a bullet in the back of any officer’s head who disobeys an order. And that should be a comfort in these uncomfortable times.

How far does Jeremy Hunt’s writ run?

Jeremy Hunt is a man who thinks he is in clear charge of government fiscal policy. After Liz Truss’s press conference yesterday which abandoned the corporation tax cut and opened the way to spending cuts, there were briefings to the papers that no more U-turns were coming. But on the media round on Saturday morning, Jeremy Hunt put the whole mini-Budget under review. He was clear that taxes would rise – in direct contradiction of what Truss had said on the campaign trail, spending wouldn’t go up as much as expected and that every department will have to find savings. The Sunday Times is now reporting that the cut in income tax will be delayed for a year, and return to the date that Rishi Sunak had originally proposed. We can expect Hunt to be asked about this when he appears on the BBC’s Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg. But the shift is another reminder that little remains of the mini-Budget and its growth plan.

But on the media round this morning, Jeremy Hunt put the whole mini-Budget under review

Hunt’s prescription of tax rises and spending cuts is the precise opposite of what Truss was offering during the leadership campaign. But as the government struggles to regain market credibility, this is what it is having to offer. Truss, who is now a prisoner of her Chancellor – imagine the market reaction if he quit, has to go along with it: she is in office but not in power. Even her longer-term promises, such as her pledge to get defence spending up to three percent of GDP by 2030, now appear to be in doubt.

There is an intriguing question about how much Hunt’s power as chief executive, to use his close ally Steve Brine’s phrase, extends into other areas. For example, Hunt is an advocate of interventionist public health policies, arguing they’ll reduce the medium term burden on the NHS. But Truss emphasised in her conference speech how she was junking the ban on buy one, get one free offers which would have applied to unhealthy foods and was meant to be one of the government’s anti-obesity interventions. Will Hunt push for a rethink on that?

Hunt may well buy the government some time with the markets. After Truss’s appearance yesterday, there were worries that the government didn’t yet accept the level of fiscal consolidation that was necessary. Hunt’s words today will have gone some way to dealing with that concern. But for this approach to work, all the cabinet will have to stick to the same script and the plan the government presents at the end of the month will have to be credible.

What if Jeremy Hunt’s rebooted centrism doesn’t calm the markets?

He will control spending, reverse the few remaining tax cuts that are still in the works, and bring in every kind of official body imaginable to check over all the figures. Jeremy Hunt made the best of a very difficult hand of cards in his first outing as Chancellor on Saturday morning. He was calm, rational, sensible, and conciliatory. His strategy was clear enough. To calm the markets, and buy the government some breathing space while it figures out what to do next. There is a catch, however. What if it doesn’t work?

Hunt’s real problem is that he has no plan for growth

Hunt’s plans as Chancellor are clearly very different from his short-lived predecessor. In a nutshell, it is George Osborne Mark II. There will be some hardcore austerity, with a clampdown on spending in every department, with a few tweaks for entrepreneurs and small businesses on the side, but it will be dressed up in centrist, compassionate language to make it more palatable. Funnily enough, there was no mention of his plan in the summer, when he stood for leader, of cutting corporation tax to 16 per cent. It will be sold as a ‘grown-up’ solution to the UK’s problems. The IMF may well find something nice to say about it, banks such as UBS may stop describing the government to investors as a ‘doomsday cult ‘, and, heck, who knows, maybe even the FT will find something positive in the programme. With some luck, the financial markets will move on to worrying about the sinking Japanese yen or rising Italian debt.

There is a problem however. It may not work. The markets are clearly already very worried about the UK’s debt. Even with the reversal on corporation tax and the higher rate there is still a big hole in the government’s finances. Add in the impact of those tax rises – because a recession is now inevitable – and we may be under even more pressure than we were before. And as interest rates rise, there may be more shocks ahead, similar to the losses in the pension system that emerged as gilt yields started to rise. After all, the UK has a huge financial sector and one of the most leveraged systems anywhere, plus a financial regulator that obviously doesn’t have a clue what is being traded in the City. It is hardly clear that we are in a better position now than we were forty-eight hours ago.

Hunt’s real problem is that he has no plan for growth. He doesn’t have a story to spin that while it may be radical the UK will start growing more rapidly in 2023 and 2024 as his reforms start to work. Nor does he have the ambition to take on the Bank of England or the currency traders. True, he may well get away with it. By sounding sensible, he may keep everything under control, and be able to spend a year and half controlling public spending before handing over Number 11 to Labour’s Rachel Reeves in good order. But if the attacks on sterling and the gilts market resume he will be in real trouble – and worst of all he will have nothing to come back with.

Jeremy Hunt thought he was being pranked

When Jeremy Hunt received a message early yesterday morning from a ‘Liz Truss’ wanting to talk to him, he assumed he was being pranked. He later found out it was indeed the prime minister and she wanted to make him Chancellor. He has totally reset her economic policy this morning, so maybe the prank is on her.

He has totally reset her economic policy this morning, so maybe the prank is on her

I have just interviewed him, and what he told me is that in what he now says will in effect be a ‘full budget’ on 31 October, he will announce public spending plans that are lower than those previously announced (otherwise known as spending cuts), plus tax rises and some taxes not falling as fast as hoped (that promised 1p reduction in the basic rate of tax is at risk).

There will be a panoply of painful consolidating measures to eliminate a black hole in the public finances that is probably still £40 billion even after yesterday’s u-turn decision to increase corporation tax to raise £18 billion. He says that apart from stabilising the public finances, and thereby (he hopes) reassuring investors and markets, his priority is to protect the most vulnerable and those on lowest incomes.

So he ‘hopes’ to increase universal credit and benefits by the 10 per cent rate of inflation, but can’t make that decision today. I put to him that he is the strongest chancellor in history, because Truss is so weak after the chaos of the past few weeks and the way bond prices sunk after her press conference yesterday, she hasn’t the power to countermand any measure he deems necessary. If she even thought of sacking him, she would be toast. He didn’t engage with that, insisting instead they are a team, and that it is in the national interest she survives as PM. If that is right, however, the new chancellor may be in the unusual position of being the team captain.

The Chancellor could take the tax burden even higher

This morning on the media round, Jeremy Hunt followed in the footsteps of Tory chancellors before him warning about the ‘very difficult decisions’ that lie ahead. The new chancellor’s language and tone could easily be compared to George Osborne after the financial crisis, explaining to the country why government spending needed to be curbed. Or to Rishi Sunak, towards the end of the crisis stage of the pandemic, who was constantly reminding MPs and the public about the ‘difficult times ahead’ due to the fallout from economic shutdowns and unprecedented peacetime spending.

The crucial difference, however, is that this new talk of spending cuts and higher taxes is in response to a crisis of the government’s own making. Yes, rising interest rates and costs for government borrowing are going up worldwide: but Liz Truss’s mini-Budget last month put the UK in the spotlight, and the UK’s borrow-and-spend agenda (which mirrors most Western countries right now) became most heavily punished by the markets.

So the new chancellor is working hard, and quickly, to shed the UK of its outlier position; to get markets, if not back on side, at least calmer than they have been in recent weeks. His comments this morning are clearly designed to take a lesson from (very recent) history, and not spook the markets over the weekend. Hours after the mini-Budget last month, the pound started falling and gilt yields started rising – but it was former chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s comments on the Sunday about going even bigger and bolder with unfunded tax cuts that saw the pound drop to its lowest level against the dollar on record the next day, and set government borrowing costs soaring to the point when the Bank of England had to intervene.

Yesterday, after the Prime Minister’s announcements, gilt yields started rising again. Hunt will be desperate to avoid a repeat of last month’s debacle, and his language this morning represented a clear break with former defiant attitudes, insisting that what ‘the country needs now is stability.’

But this stability now comes at a very hefty price. For all the trouble Truss’s mini-Budget has caused the economy, her original fiscal plans brought the tax burden – currently at a 72-year high – back down to 2021 levels. Not an especially dramatic reduction. But based on Hunt’s comments this morning, it seems the new fiscal strategy may take the tax burden even higher, as he bluntly stated that ‘some taxes will have to go up.’

Not only is this a clear break from the Trussonomics agenda guiding the government’s fiscal decisions over the past few months – it also raises questions about what this government’s new ‘pro-growth’ strategy will be. Truss has linked economic flourishing directly to tax breaks, for individuals and companies; she reneged on the latter yesterday in her pivot on corporation tax. If the whole tax narrative goes out the window, what will she say her new plan for growth is?

It is likely to be a question that goes unanswered until after the new chancellor gets through his ‘medium-term fiscal plan’ at the end of the month. But what’s in that plan – the tax updates, the spending cuts, the ever-changing incentives for businesses to invest – will play a large part in determining what the government does next. Hunt’s media round this morning suggested these decisions are increasingly out of the prime minister’s control.

We’re in dark days for market liberalism

If there is anything that the swift overturning of Prime Minister Liz Truss’s purported free market revolution has taught us, it is the utter lack of enthusiasm for economic liberalisation à la Reagan and Thatcher across the West right now.

Yes, the lousy roll-out of the mini-budget by Truss’s now ex-Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng played a role in the prime minister’s rapid and multiple U-turns. But bad-PR is only part of the story. Many Tory MPs are plainly comfortable with the economic arrangements prevailing in Britain that successive Conservative governments have not challenged since the Tories returned to power in 2010.

For despite the mythologies about nefarious ‘neoliberals’ ruling the world, the truth is that we live in economic conditions in which cronyism, collusion, and corporatism (the three ‘Cs,’ as I call them) are increasingly the norm in Western economies.

People in Britain may say that they despise technocrats, bureaucrats, and civil servants. Yet many of the same voters oppose rolling back the welfare state or challenging the quasi-divine status accorded to Britain’s National Health Service

That’s why some of the richest counties in America are in and around Washington D.C. It’s a city whose lifeblood isn’t private enterprise but rather lobbying and influence-peddling. It’s also why we see a revolving door between government jobs, Wall Street firms, and management consultancy outfits like Goldman Sachs (a.k.a. Government Sachs). That corporatist nexus is where the big money is to be found. Why take the greater risk of being entrepreneurial in the private economy when you can be a wealthy rent-seeker?

Given such sentiments, it takes courage to challenge the cozy relationships between legislators, government officials, lobbyists, well-connected businesses, and regulators that characterises many Western economies. But another factor which is crippling market liberalism these days is the electorate’s disinterest in and even hostility to economic liberalisation agendas.

Among the Tory MPs who opposed Truss’s now-defunct agenda, many clearly lacked confidence in the electorate’s willingness to accept the necessity of market liberalising reforms. Again, this is a broad phenomenon across Western countries.

People in Britain may say that they despise technocrats, bureaucrats, and civil servants. Yet many of the same voters oppose rolling back the welfare state or challenging the quasi-divine status accorded to Britain’s National Health Service. Likewise, there is no shortage of Americans who want lower taxes. Yet plenty of those Americans—including many conservatives—will resist any substantial rollback of the entitlements that they have come to expect as the norm.

This adds up to a distinctly unhealthy set of political and economic conditions that is making the free market case incredibly difficult to sell in our time. In the late-1970s and 1980s, there were political leaders, intellectuals, and many voters fed up with the status quo of high unemployment, inflation, and low growth produced by thirty years of neo-Keynesian interventionism. They were consequently willing to support market-orientated changes. Who and where are those leaders and voters today?

My fear is that many Western economies are sliding into a situation whereby entire constituencies of people now exist who regularly support politicians who promise that, in return for their votes, these groups’ expectations (corporate welfare, bailouts for the ‘too-big-to fail,’ welfare entitlements, etc.) will be met and raised.

The problem is that this isn’t economically sustainable, as these conditions impede the dynamism, competition, and economic growth that delivers long-term prosperity.

Liz Truss recognised that growth must be today’s priority, and that economic liberalisation delivers it. That much of her own party and many right-leaning voters wouldn’t go along with the hard economic changes that so many Western economies desperately need to reignite growth does not augur well for Western nations’ economic future.

Why Liz Truss failed

The markets did not crash, so there was not a Black Friday in the way some had envisaged. But this certainly was Black Friday for the Tories, a new low in the party’s history, a debacle to rival Black Wednesday but with none of the economic dividends. A new Prime Minister sacks a Chancellor for doing exactly what she told him to, then declares she will implement every single one of the corporation tax rises that she had spent the summer promising to stop. So it now emerges that Liz Truss stood for leader on a false prospectus, promising an agenda she has quickly proved unable to deliver.

Her plan during her campaign was £30 billion of unfunded tax cuts – in a government that takes almost £1,000 billion a year in taxes, this was doable. But at a push. She’d have to prove that the £30 billion would be stimulatory and (most of all) transitionary. Like an entrepreneur asking for a massive loan, investors would need to be persuaded that it was well thought-through and would work.

She’d have had her work cut out to pull off her £30 billion package. But in her mini-budget she upped it to an undoable £110 billion – via a staggering, needlessly expensive £10bn-a-month energy bill bailout. So: a borrow-and-spend splurge, dressed up language of supply-side tax reform. She then tapped the markets for an extra £60 billion and dared them to defy her – at precisely the time when those markets had started a worldwide, long-delayed rebellion against fiscally incontinent governments. When a storm was raging through world bond markets, Truss made Britain the lightning conductor – running atop the hill and calling it bravery. She went from daring to crazy then seemed to revel in the craziness, as if the implausibility of her plan was in itself proof of her courage.

The Sunakite campaign criticism was even an £30 billion cut in National Insurance was financial suicide. This was overdone. Had she constrained herself to original plan, she might have succeeded. But her untargetted, uncapped energy bailout plan saw her reach in a panic for a ruinously expensive solution which, when added to her tax cuts, made the whole package unworkable. Not, of course, that we ever saw the whole package: the spending-restraint part of it was dangled, but never delivered. It probably never existed.

I’m no fan of Trussonomics – and think even the word gives her agenda greater coherence than it ever had. What we just saw was just bungling, of an epic and historic nature. A first-time skier went off-piste, with Bond themes in her headphones, picked up speed – then hit a tree quickly. But it’s not just her: this pile-up involves much of the Conservative party. That doesn’t mean it was futile to try to get down from the mountain of big-state conservatism: just that you need a careful plan and a good bit of skill to do so. Truss shouted out ‘who dares wins,’ disappeared over the edge and that was the end of that. Sunak’s refrain – who dares loses – was not much more inspiring.

My own thoughts now haven’t moved on much from The Spectator’s verdict of Truss during the leadership campaign:-

‘The debacle [over her regional pay u-turn] underlines the main criticism of Truss’s campaign: that it all unravels fairly quickly once you begin to ask hard questions. This is why many low-tax Tories worry: if she fails, it risks making a mockery of the idea that there is an alternative to big-state conservatism. [She offers] more triple-lock pension spending, more economic distortion. And more cakeism: promises of tax cuts, without any serious discussion about the painful choices ahead if Britain is to make government more affordable. To attempt reform without a proper plan is to guarantee failure.’

The failure happened in weeks, rather than months or years. She won’t last very long in office now: she’s a busted flush, a simulacrum. The Tories will now try to work out what happens next: a unity candidate, or civil war? We’ll see. But don’t think things can’t get worse. Adam Smith once observed that there is a lot of ruin left in a nation and I suspect the same is true for the Tories. Lucky old Starmer.

Jeremy Hunt: there are ‘very difficult decisions’ ahead

Liz Truss made two big moves on Friday in a bid to calm the markets and save her premiership. The first was to announce that she was ditching plans to cancel the scheduled corporation tax rise. The second was that she had sacked her chancellor and long standing ally Kwasi Kwarteng – bringing Jeremy Hunt in as his successor. There have been lots of problems when it comes to the fallout from the not-so-mini Budget but the thing that really focussed minds in No. 10 was a preview of the OBR forecast last Friday which pointed to a financial blackhole as a result of unfunded tax cuts and the energy package. It was viewed as so bad that something needed to change when it came to the government’s plans.

That change appears to now mean an entirely new economic outlook. Hunt embarked on a media round this morning setting out his plan for the British economy now he is in No. 11. When Kwarteng gave an interview the Sunday after his fiscal event, he suggested more tax cuts would be coming. It spooked the markets further. Hunt’s message couldn’t be further from that. In an extraordinary turnaround for the Truss government, Hunt told Sky News there are ‘very difficult decisions ahead on spending and tax’:

‘The thing that people want, the markets want, the country needs now is stability. No Chancellor can control the markets but what I can do is show that we can pay for our tax and spending plans. That is going to mean some very difficult decisions on both spending and tax. But that is what I must do now so people who are worried about their mortgage costs going up, people who are worried about how they’re going to get through winter with the cost of living crisis, people in the NHS who are worried about the pressures their facing can be reassured that the the fundamental stability they need and expect from the government is there.’

On taxes, Hunt told the BBC:

‘Taxes are not going to come down by as much as people hoped, and some taxes will have to go up.’

He also said economic growth remained the end goal:

‘If we’re going to fund the NHS and our public services and keep taxes down we have to solve the growth paradox.’

Now the suggestion from Hunt that some taxes will go up and there could be spending cuts in order to balance the books isn’t exactly revolutionary. Economists, politicians and journalists have been pointing to the fact that Truss would need to find some way to fill the financial blackhole. Yet the Prime Minister has been incredibly reluctant to entertain the idea. Even at Prime Minister’s Questions this week, she promised no spending cuts. It follows that Hunt’s interview is a stark reminder of how much has changed in the past 24 hours – and how Truss’s initial political project of Trussonomics and radicalism is no more. Hunt suggested he would be taking his own approach regarding the coming fiscal event – meaning some taxes will not be cut as quickly as they want. That group presumably includes Truss. He suggested that overall public spending will continue to rise (pointing to the cost of the energy price guarantee) but departmental cuts would be coming. Hunt distanced himself from Kwarteng and Truss’s original fiscal event suggesting parts of it were misguided as it was ‘a mistake to fly blind’: ‘The way we went about it clearly wasn’t right and that’s why I’m sitting here now.’

The new chancellor is ultimately unsackable at least in the medium term given his appointment is meant to prop Truss up. His friend Steve Brine told Radio 4 on Friday that people should ‘see Liz Truss as chairman and Jeremy as chief executive’. It suggests Truss has very little say now on the economy. Yet Hunt’s comments today will undoubtedly rile many of Truss’s MP backers who picked her over Sunak in large because of her central promise of a low tax economy. Others will take issue with his criticism of Kwarteng. Hunt’s main audience today, however, was not MPs. Instead, it’s the markets. After Truss’s painful press conference on Friday, the markets remained jittery. There was a big sell-off in the gilt market, suggesting the reversing of the £18bn tax cut was not enough to convince investors the UK was on a sustainable fiscal path. These interviews by Hunt are meant to signal just that.

Why boys fall behind

What do you know about Finland? That it is the happiest nation on earth? Correct. That the school system is superb? Well, half right. Finland does indeed always rank at or near the top of the international league table for educational outcomes – but that’s because of the girls. Every three years, the OECD conducts a survey of reading, mathematics, and science skills among 15-year-olds. It is called the Pisa (Programme for International Student Assessment) test, and it gets a lot of attention from policy makers.

Finland is a good place to look at gender gaps in education because it is such a high-performing nation (indeed, one could say that other countries suffer from a bout of Finn envy every time the Pisa results are published). But although Finnish students rank very high for overall performance on Pisa, there is a massive gender gap: 20 per cent of Finnish girls score at the highest reading levels in the test, compared to just 9 per cent of boys. Among those with the lowest reading scores, the gender gap is reversed: 20 per cent of boys versus 7 per cent of girls. On most measures, Finnish girls also outperform the boys in science and in mathematics.

The bottom line is that Finland’s internationally acclaimed educational performance is entirely explained by the stunning performance of Finnish girls. (In fact, American boys do just as well as Finnish boys do on the Pisa reading test.)

This may have some implications for the education reformers who flock to Finland to find ways to bottle the nation’s success, but it is just an especially vivid example of an international trend. In elementary and secondary schools across the world, girls are leaving boys behind. Girls are about a year ahead of boys in terms of reading ability in OECD nations, in contrast to a wafer-thin and shrinking advantage for boys in maths. Boys are 50 per cent more likely than girls to fail at all three key school subjects: maths, reading, and science. Sweden is starting to wrestle with what has been dubbed a pojkkrisen (boy crisis) in its schools. Australia has devised a reading program called Boys, Blokes, Books and Bytes.

In the US, girls have been the stronger sex in school for decades. But they are now pulling even further ahead, especially in terms of literacy and verbal skills. The differences open up early. Girls are 14 percentage points more likely than boys to be ‘school ready’ at age five, for example, controlling for parental characteristics. This is a much bigger gap than the one between rich and poor children, or black and white children, or between those who attend pre-school and those who do not.

A six-percentage-point gender gap in reading proficiency in fourth grade widens to an 11-percentage-point gap by the end of eighth grade. In maths, a six-point gap favouring boys in fourth grade has shrunk to a one-point gap by eighth grade. In a study drawing on scores from the whole country, Stanford scholar Sean Reardon finds no overall gap in maths from grades three through eight, but a big one in English. ‘In virtually every school district in the United States, female students out-performed male students on ELA [English Language Arts] tests,’ he writes. ‘In the average district, the gap is… roughly two-thirds of a grade level and is larger than the effects of most large-scale educational interventions.’

By high school, the female lead has solidified. Girls have always had an edge over boys in terms of high school grade point average (GPA), even half a century ago, when they surely had less incentive than boys given the differences in rates of college attendance and career expectations. But the gap has widened in recent decades. The most common high school grade for girls is now an A; for boys, it is a B. As figure 1.1 shows, girls now account for two-thirds of high schoolers in the top ten per cent, ranked by GPA, while the proportions are reversed on the bottom rung.

Girls are also much more likely to be taking Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate classes. Of course, national trends disguise huge variations by geography, so it is useful to zoom in and look at specific places. Take Chicago, where students from the most affluent neighbourhoods are much more likely to have an A or B average in ninth grade (47 per cent), compared to those from the poorest (32 per cent). That is a big class gap, which, given that Chicago is the most segregated big city in the country, means a big race gap too. But strikingly, the difference in the proportion of girls versus boys getting high grades is the same: 47 per cent to 32 per cent. If you’re wondering whether grades in the first year of high school matter much, they do, strongly predicting later educational outcomes. As the Chicago researchers who analysed these data insist, ‘Grades reflect multiple factors valued by teachers, and it is this multidimensional quality that makes grades good predictors of important outcomes.’

It is true that boys still perform a little better than girls do on most standardised tests. But this gap has narrowed sharply, down to a 13-point difference in the SAT, and it has disappeared for the ACT. It is also probably worth noting here that SAT and ACT scores matter a lot less in any case, as colleges move away from their use in admissions, which, whatever other merits this has, seems likely to further widen the gender gap in postsecondary education. Here is a more anecdotal example of the gender gap: every year the New York Times runs an editorial contest among middle and high school students, and it publishes the opinions of the winners. The organisers tell me that among the applicants, there is a ‘2:1, probably closer to 3:1’ ratio of girls to boys.

By now it should not be a surprise to learn that boys are less likely than girls to graduate high school. In 2018, 88 per cent of girls graduated from high school on time (i.e. four years after enrolling), compared to 82 per cent of boys. The male graduation rate is only a little higher than the 80 per cent among poor students.

One factor that gets too little attention in these debates is the developmental gap, with the male prefrontal cortex struggling to catch up with the female one well into the early twenties

You might think these were easy numbers to come by – a quick Google search away. I thought they would be when I started writing this. In fact it took a small Brookings research project to figure it out, and for reasons that are instructive. States are required by federal law to report high school graduation rates by race and ethnicity, proficiency in English, economic disadvantage, homelessness, and foster status. These kinds of data are invaluable for assessing trends for the groups at greatest risk of dropping out. But oddly, states do not have to report their results by sex. Getting the numbers cited above required scouring the data for each state.

An energetic non-profit alliance, Grad Nation, is seeking to raise the overall high school graduation rate in the US to 90 per cent (up from 85 per cent in 2017). This is a great goal. The alliance points out that this will require improvements among ‘students of colour, students with disabilities, and low-income students.’ It definitely will. But they missed a big one – boys. After all, girls are only two percentage points from the target, while boys are eight percentage points below it.

What is going on here? There are many potential explanations. Some scholars link the relative underperformance of boys in school to their lower expectations of post-secondary education, surely the very definition of a vicious circle. Others worry that the strong skew toward female teachers – three out of four and rising – could be putting boys at a disadvantage. This matters, for sure. But I think there is a bigger, simpler explanation staring us in the face. Boys’ brains develop more slowly, especially during the most critical years of secondary education. When almost one in four boys (23 per cent) is categorised as having a ‘developmental disability,’ it is fair to wonder if it is educational institutions, rather than the boys, that are not functioning properly.

In Age of Opportunity: Lessons from the New Science of Adolescence, Laurence Steinberg writes that ‘high-school aged adolescents make better decisions when they’re calm, well rested, and aware that they’ll be rewarded for making good choices.’ To which most parents, or anybody recounting their own teen years, might respond: tell me something I don’t know.

But adolescents are wired in a way that makes it hard to ‘make good choices.’ When we are young, we sneak out of bed to go to parties; when we get old, we sneak out of parties to go to bed. Steinberg shows how adolescence is essentially a battle between the sensation-seeking part of our brain (Go to the party! Forget school!) and the impulse-controlling part (I really need to study tonight).

It helps to think of these as the psychological equivalent of the accelerator and brake pedals in a car. In the teenage years, our brains go for the accelerator. We seek novel, exciting experiences. Our impulse control – the braking mechanism – develops later. As Robert Sapolsky, a Stanford biologist and neurologist, writes in his book Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, ‘The immature frontal cortex hasn’t a prayer to counteract a dopamine system like this.’ There are obvious implications here for parenting, and the importance of helping adolescents develop self-regulation strategies.

Adolescence, then, is a period when we find it harder to restrain ourselves. But the gap is much wider for boys than for girls, because they have both more acceleration and less braking power. The parts of the brain associated with impulse control, planning, future orientation, sometimes labelled the ‘CEO of the brain,’ are mostly in the prefrontal cortex, which matures about two years later in boys than in girls.

The cerebellum, for example, reaches full size at the age of 11 for girls, but not until age 15 for boys. Among other things, the cerebellum ‘has a modulating effect on emotional, cognitive, and regulatory capacities,’ according to neuroscientist Gokcen Akyurek. These findings are consistent with survey evidence on attention and self-regulation, where the biggest sex differences occur during middle adolescence, in part because of the effect of puberty on the hippocampus, a part of the brain linked to attention and social cognition. The correct answer to the question so many teenage boys hear, ‘Why can’t you be more like your sister?’ is something like, ‘Because, Mum, there are sexually dimorphic trajectories for cortical and subcortical gray matter!’

While parts of the brain need to grow, some brain fibres have to be pruned back to improve our neural functions. It is odd to think that parts of our brain need to get smaller to be more efficient, but it’s true. The brain basically tidies itself up; think of it like trimming a hedge to keep it looking good. This pruning process is especially important in adolescent development, and a study drawing on detailed brain imaging of 121 people aged between four and 40 shows that it occurs earlier in girls than in boys. The gap is largest at around the age of 16. Science journalist Krystnell Storr writes that these findings ‘add to the growing body of research that looks into gender differences when it comes to the brain… the science points to a difference in the way our brains develop. Who can argue with that?’ (It turns out, quite a few people. But I’ll get to that later.)

It is important to note, as always, that we are talking averages here. But I don’t think this evidence will shock many parents. ‘In adolescence, on average girls are more developed by about two to three years in terms of the peak of their synapses and in their connectivity processes,’ says Frances Jensen, chair of the department of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. ‘This fact is no surprise to most people if we think of 15-year-old boys and girls.’ I don’t have any daughters, but I can report that when my sons brought female friends home during the middle and high school years, the difference in maturity was often startling.

The gender gap in the development of skills and traits most important for academic success is widest at precisely the time when students need to be worrying about their GPA, getting ready for tests, and staying out of trouble. A 2019 report on the importance of the new science of adolescence from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine suggests that ‘sex differences in associations between brain development and puberty are relevant for understanding… prominent gender disparities during adolescence.’ But this emerging science on sex differences in brain development, especially during adolescence, has so far had no impact on policy. The chapter on education in the National Academies report, for example, contains no specific proposals relating to the sex differences it identified.

The debate over the importance of neurological sex differences, which can be quite fierce, is wrongly framed as far as education is concerned. There are certainly some biologically based differences in male and female psychology that last beyond adolescence. But by far the biggest difference is not in how female and male brains develop, but when. The key point is that the relationship between chronological age and developmental age is very different for girls and boys. From a neuro-scientific perspective, the education system is tilted in favour of girls. It hardly needs saying that this was not the intention. After all, it was mostly men who created the education system; there is no century-old feminist conspiracy to disadvantage the boys. The gender bias in the education system was harder to see when girls were discouraged from pursuing higher education or careers and steered toward domestic roles instead. Now that the women’s movement has opened up these opportunities to girls and women, their natural advantages have become more apparent with every passing year.

The gender gap widens further in higher education. In the US, 57 per cent of bachelor’s degrees are now awarded to women, and not just in stereotypically ‘female’ subjects: women now account for almost half (47 per cent) of undergraduate business degrees, for example, compared to fewer than one in ten in 1970. Women also receive the majority of law degrees, up from about one in twenty in 1970.

Women are earning three out of five master’s degrees and associate’s degrees, and the rise has been even more dramatic for professional degrees. The share of doctoral degrees in dentistry (DDS or DMD), medicine (MD), or law (JD or LLB) being awarded to women has jumped from 7 per cent in 1972 to 50 per cent in 2019. The dominance of women on campus shows up in nonacademic areas too. In 2020, the law review at every one of the top sixteen law schools had a woman as editor-in-chief.

As Rosin noted, this is a global trend. In 1970, the year after I was born, just 31 per cent of undergraduate degrees went to British women. When I left college two decades later, it was 44 per cent. Now it is 58 per cent. Today, 40 per cent of young British women head off to college at the age of 18, compared to 29 says of their male peers. ‘The world is waking up to… this problem,’ says Eyjolfur Gudmundsson, rector of the University of Akureyri in Iceland, where 77 per cent of the undergraduates are women. Iceland is an interesting case study, since it is the most gender egalitarian country in the world, according to the World Economic Forum. But Icelandic universities are struggling to reverse a massive gender inequality in education. ‘It’s not being discussed in the media,’ says Steinunn Gestsdottir, vice rector at the University of Iceland. ‘But policymakers are worried about this trend.’ In Scotland, policymakers are past the worried stage and into the doing-something-about-it stage, setting a clear goal to increase male representation in all Scottish universities. Their approach is one that other countries should follow.

It is true that some subjects, such as engineering, computer sciences and maths, still skew male. Considerable efforts and investments are being made by colleges, non-profit organisations, and policymakers to close these gaps in Stem (science, technology, engineering, and math). Women now account for 36 per cent of the undergraduate degrees awarded in Stem subjects, including 41 per cent of those in the physical sciences and 42 per cent in mathematics and statistics.

But there have been no equivalent gains for men in traditionally female subjects, such as teaching or nursing, and these are occupational fields likely to see significant job growth.

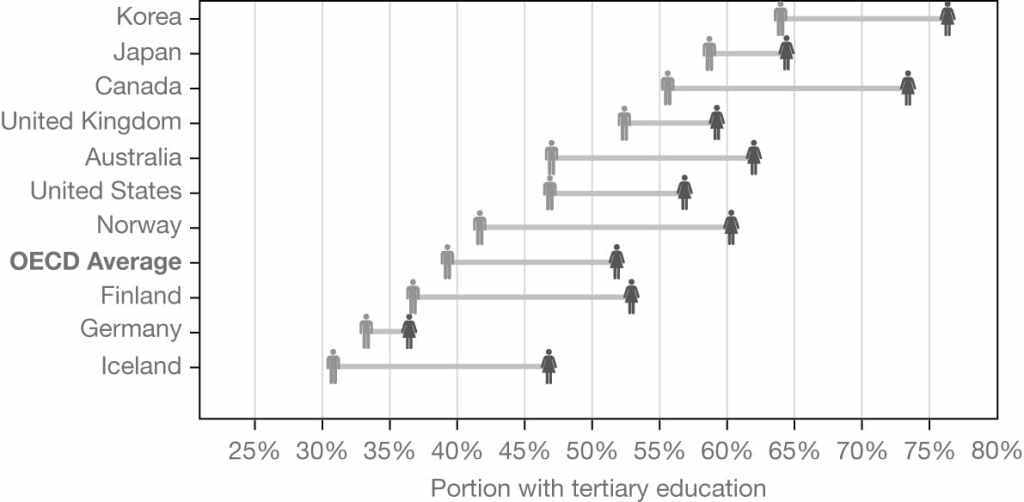

In every country in the OECD, there are now more young women than young men with a bachelor’s degree. Figure 1.3 below shows the gap in some selected nations. As far as I can tell, nobody predicted that women would overtake men so rapidly, so comprehensively, or so consistently around the world.

Almost every college in the US now has mostly female students. The last bastions of male dominance to fall were the Ivy League colleges, but every one has now swung majority female. The steady feminisation of college campuses may not trouble too many people, but there is at least one group whose members really worry about it: admissions officers. ‘Once you become decidedly female in enrolment,’ writes Jennifer Delahunty, Kenyon College’s former dean of admissions, ‘fewer males and, as it turns out, fewer females find your campus attractive.’ In a provocative New York Times opinion piece, plaintively headlined ‘To All The Girls I’ve Rejected,’ she said publicly what everyone knows privately: ‘Standards for admission to today’s most selective colleges are stiffer for women than men.’

The evidence for this stealthy affirmative action program in favour of men seems quite clear. At private colleges the acceptance rates for men are considerably higher than for women. At Vassar, for example, where 67 per cent of matriculating students are female, the acceptance rate for male applicants in fall 2020 was 28 per cent, compared to 23 per cent for women. You might be wondering if this is because Vassar was a women’s college until 1969. But Kenyon, which was all-male until the same year, has a similar challenge.

By contrast, public colleges and universities, which educate the vast majority of students, are barred from discrimination on the basis of sex. This is one reason they skew even more female than private institutions.

As Kenyon’s Delahunty put it candidly in a September 2021 interview with the Wall Street Journal, ‘Is there a thumb on the scale for boys? Absolutely. The question is, is that right or wrong?’ My answer is that it is wrong. Even though I am deeply worried about the way boys and men are falling behind in education, affirmative action cannot be the solution.

To a large extent, the gaps at the college level reflect the ones in high school. Differences in early attainment at college can be explained by differences in high school GPA, for example. Reading and verbal skills strongly predict college-going rates, and these are areas where boys lag furthest behind girls. Equalising verbal skills at age 16 would close the gender gap in college enrolment in England, according to a study by Esteban Aucejo and Jonathan James. The most urgent task, then, is to improve outcomes for boys in the K–12 school system.

Getting more men to college is just the first step. They also need help getting through college. With most students now going to some kind of college at some point, the big challenge is completion. Here, too, there is a gender gap. Male students are more likely to ‘stop out,’ that is, to take a detour away from their studies, and they are also more likely to ‘drop out’ and fail to graduate at all. The differences are not trivial: 46 per cent of female students enrolling in a public 4-year college have graduated 4 years later; for male students, the proportion is 35 per cent. (The gap shrinks somewhat for six-year graduation rates.)

In 2019, Matthew Chingos, director of the Centre on Education Data and Policy at the Urban Institute, in collaboration with the New York Times, created a league table of colleges based on their dropout rates. To judge the performance of institutions fairly, Chingos took into account the kind of students they enrolled, since ‘on average, colleges have lower graduation rates when they enrol more lower-income students, more black and Latino students, more men, more older students and more students with low SAT or ACT scores.’ In other words, colleges should not be penalised for having higher dropout rates because they enrol more disadvantaged students. When I read that article, the addition of ‘more men’ in that category jumped out. It shows that the educational underperformance of half the population is now a routine fact to social scientists, one to be added to the standard battery of statistical controls.

The numbers from Chingos suggest that all else equal, an all-female four-year school would have a graduation rate 14 percentage points higher than an all-male school. This is not a small difference. In fact, taking into account other factors, such as test scores, family income, and high school grades, male students are at a higher risk of dropping out of college than any other group, including poor students, black students, or foreign-born students.

But the underperformance of males in college is shrouded in a good deal of mystery. World-class scholars have pored over the low rates of male college enrolment and completion, piling up data and running regressions. I have read these studies and spoken to many of the scholars. The short summary of their conclusions is: ‘We don’t know.’ economic incentives do not provide an answer. The value of a college education is at least as high for men as for women. even a scholar like MIT’s David Autor, who has dug deeply into the data, ends up describing male education trends as ‘puzzling.’ Mary Curnock Cook, the former head of the UK’s university and college admissions service, says she is ’baffled.’ When I asked one of my sons for his thoughts, he looked up from his phone, shrugged, and said, ‘I dunno.’ Which may in fact have been the perfect answer.

One factor that gets too little attention in these debates is the developmental gap, with the male prefrontal cortex struggling to catch up with the female one well into the early twenties. To me, it seems clear that girls and women were always better equipped to succeed at college, just as in high school, and that this has become apparent as gendered assumptions about college education have fallen away.

I think there is an aspiration gap here too. Most young women today have it drummed into them how much education matters, and most want to be financially independent. Compared to their male classmates, they see their future in sharper focus. In 1980, male high school seniors were much more likely than their female classmates to say they expected to get a four-year degree, but within just two decades, the gap had swung the other way.

This may also be why many educational interventions, including free college, benefit women more than men; their appetite for success is just higher. Girls and women have had to fight misogyny without. Boys and men are now struggling for motivation within.