-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Britain’s worst council leader given gong

For months now, Mr S has chronicled the tribulations of Susan Aitken, who is the first SNP leader of Glasgow City Council and appears determined to be the last, too. She has presided over a waste crisis in which refuse-strewn streets have become a familiar sight even in the city’s leafier suburbs and which threatened to embarrass locals on the world stage ahead of COP26.

Challenged on this, Aitken insisted Glasgow needed only ‘a spruce up’. When that didn’t work, she trained her fire on her critics, detecting in the concerns of the GMB union ‘a real echo of the language that some far-right organisations have used’ and telling Sir Keir Starmer he was ‘on pretty shaky ground as a London MP, coming up and telling Glasgow that we’re filthy’. Thereafter, she went on to blame the waste row on everyone from ‘a wee ned [non-educated delinquent] with a spray can’ to Margaret Thatcher.

As such, Mr S was tickled to see Aitken named Leader of the Year at Wednesday’s ‘Cllr Awards’, organised by the Local Government Information Unit (LGIU). Introducing the shortlist, LGIU chief executive Jonathan Carr-West said:

The leader of the council is the public face of the council. They carry a huge weight on their shoulders. This year more than any other year, perhaps, they’ve had to be prepared to answer difficult questions as we move into recovery. They’ve had to ensure that they are accountable and the shortlist for Leader of the Year is a testament to the power of effective leadership and the ability of council leaders to stand up for their communities.

Almost as glitzy as the Cllr Awards is The Spectator‘s Parliamentarian of the Year bash, which was also held yesterday. An oversight meant that one winner was not announced and Mr S would like to rectify that.

For his black humour and keen sense of the absurd, for the deft irony with which wields locutions such as ‘prepared to answer difficult questions’ and ‘the power of effective leadership’, Satirist of the Year goes to Jonathan Carr-West.

When did traditional masculinity become toxic?

It’s hard for privileged white men to stay relevant in this age of identity politics but a number of fail-safe strategies have begun to emerge. Prince Harry and, to a lesser extent his older brother, have captured the mental health market by publicly discussing their issues. William’s school pal Eddie Redmayne, and pretty much the entire cast of the Harry Potter films, have spoken out in defence of the transgender community. Benedict Cumberbatch is going down the feminist route.

Cumberbatch is calling time on ‘toxic masculinity’. Interviewed by Sky News ahead of the release of his latest film, a Netflix Western in which he plays the part of a rancher, Cumberbatch took the opportunity to chastise men. ‘We need to fix male behaviour,’ he implored viewers, and the first step is for men to ‘shut up and listen’.

From Harrow to Hollywood, his life has been one of privilege

I don’t know what budding actors are taught in drama schools today but the line between fact and fiction doesn’t appear to be high on the list. Redmayne has just this week apologised for playing a transgender woman in the 2015 film The Danish Girl. The part should have gone to a transgender actor, he has said. But isn’t the whole skill of acting to portray someone you are not?

Poor Cumberbatch seems similarly confused. To get with the Western vibe of his latest film, he apparently stayed in character as the charismatic cowboy Phil Burbank, ‘who inspires fear and awe in those around him,’ throughout his time on set. And it seems to be this experience that has given him insight into the problems with men. But it’s fiction, Benedict! Not only are there few ranchers nowadays but the whole cowboy fantasy, epitomised by John Wayne and portrayed in countless Hollywood westerns, has fallen out of fashion. Men have changed since the 19th century.

These actors may struggle to separate fact from fiction but they have their finger on the pulse of woke thinking. The assumption that there is something inherently wrong with men, expressed through the trope of ‘toxic masculinity,’ is very fashionable indeed. Cumberbatch has said it is important to ‘finally point out the inadequacies of the status quo’ but men are routinely presented as a problem to be solved. If toxicity isn’t exactly inscribed within their DNA, then it’s a product of their socialisation, we are told. Masculinity is considered a disease, its poison infecting not just individual men but the whole of society.

Knocking men, or the only slightly more sophisticated diagnosis of toxic masculinity, has long been a favourite feminist pastime. A peculiar strain of feminism has always maintained that the only way to raise up women is to do men down. Recently, new life has been breathed into this outdated argument by the assumption that male bad behaviour is on a spectrum, with wolf whistling and knee touching at one end and rape and murder at the other. The complete absence of evidence for such outlandish claims does not prevent their repetition.

But Cumberbatch taps into a deeper cultural trend too when he writes off stereotypically masculine values as toxic. Qualities such as courage, stoicism, strength, resilience, independence and assertiveness have become unfashionable with the cultural elite Cumberbatch very much represents. Far better, they tell us, to be gentle, caring, in touch with our emotions, open to displaying our vulnerabilities and sharing our struggles with mental health. Stoicism has given way to emotional incontinence.

But there’s a problem with this. Cumberbatch and his acting chums may do well out of public emoting but people who have to work in dangerous, physically demanding and poorly paid jobs, not so much. If I’m ever unfortunate enough to find myself trapped in a burning building, I want someone brave, strong and assertive to come to my rescue, not someone who is going to shed a tear over patriarchal social norms before asking me if I really want to be saved.

Cumberbatch is an aristocrat. His family tree is said to encompass connections to royalty and slave owners. From Harrow to Hollywood, his life has been one of privilege. He is in the luxurious position of now having a platform from which he can tell the rest of us how to live. Lucky him. But using this to assuage his personal sense of guilt while securing his own position in the woke world of film is just not on. Knocking masculinity is an elite preoccupation that not one everyone buys into. Film stars should stick to acting and ditch the preaching. Some of us want to be entertained, not educated.

The problem with masks in theatres

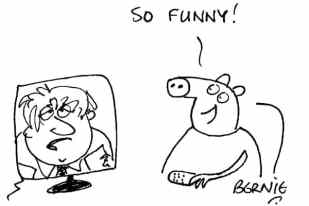

As if our beleaguered prime minister didn’t have enough to worry about, now comes another unhelpful headline. For on a mid-week trip to Islington’s most fashionable theatre, the Almeida, Boris Johnson had the misfortune to be spotted – well, snapped – by another audience member after he had temporarily removed his face-mask.

For the tutting Zero Covid fanatics of Twitter, this latest mask blunder is – of course – yet further evidence of the PM’s reckless disregard for lives and safety. For anyone who’s stepped foot in a theatre, though, Johnson’s choice will be viewed much more sympathetically. For if there’s a more irritating place on earth to wear a mask than the theatre, I’ve yet to find it.

Watching a play isn’t popping to the shops or jumping on the tube. It’s a long commitment – three hours in the case of this particular play (The Tragedy of Macbeth). That’s quite a while to tolerate something potentially obstructing your breathing. And let’s not forget that – unlike a long train journey – everyone going to the theatre does so entirely by choice. If they were that terrified of Covid, they’d have given it a miss.

And how relevant are masks to theatre performances anyway? The one thing you are forbidden from doing during a performance is talking. Assuming the audience behaves, that puts a pretty solid dent in the argument that you need masks to prevent aerosol droplets.

In the prime minister’s defence, the vast majority of theatres – the Almeida included – dropped their mask mandates months ago. Instead, they tend to make a perfectly reasonable request that audience members ‘consider’ wearing one. Just like every other establishment that doesn’t cater specifically to the medically vulnerable.

Does it work? Based on my recent visits, I’d say that around 40 per cent of audience members mask up. But a decent chunk take them off when the lights go down. Even those who prefer to play it safe seem perfectly relaxed about it. Once again, the member for Uxbridge and South Ruislip finds himself in tune with public opinion.

Perhaps that’s no surprise. For all his weird elbow-bumping piety in public, I suspect Boris soon worked out what us theatre regulars have known for a while: that having to wear a mask puts a serious dampener on a good night out. Even today, I bristle at recalling some of my visits to theatreland last autumn – back when mask rules were enforced to the point that even a momentary lapse could attract a visit from a hissing usher.

I remember one particularly ludicrous incident when, having purchased a double gin and tonic (from the theatre’s own bar), I was told that – if I wanted to drink it during the performance – I should do so ‘as quickly as possible’, so as to minimise the time spent unmasked. Even in a year of perverse health and safety rules, that was a new one: ‘You’d better down that liquor quickly. For your own good!’

There were other silly impositions, too. Irritating one-way systems. No access to the toilets after the show. Having to show up 30 minutes early (in the case of the National) to be checked-in airline style and escorted to your seat. But it was the ubiquitous mask regime that succeeded in squeezing the joy from the whole experience.

So let’s not condemn Boris for choosing to exercise his right to go maskless at the Almeida – a choice probably echoed by half of those in the stalls. The arts are supposed to be about free expression – or, for most punters, a bit of escapism – and an antidote to puritanism. Given their propensity for staying indoors, we can probably safely assume the Zero Covid lot don’t venture to the theatre that often. But must they impose their social codes on those that do?

Let’s focus instead on those far more serious rumours – posted online by those claiming to have been there – that the prime minister committed the grievous sin of nattering throughout the performance. For, as any theatre lover will tell you, this is the far graver crime.

Boris must act to prevent a repeat of the Channel migrant tragedy

The tragic drowning of more than two dozen people in the English Channel yesterday should remind us that closing down this irregular migration route has become a multi-purpose moral duty. Not only does the British state have a responsibility to do so to preserve its social contract with its citizens and the integrity of the nation, but also to protect lives.

The large-scale loss of life that took place was the proverbial accident that had been waiting to happen. There has been a spate of smaller-scale drownings in recent weeks and it was only a matter of time before a fully laden, sizeable inflatable capsized or sank.

Boris Johnson reacted to the tragedy by finally calling a Cobra meeting to discuss immediate action to prevent a repeat. The French authorities made several arrests of suspected people traffickers. It’s amazing what can be done when inertia is no longer an option.

So where is this tragic story heading and how can Johnson get ahead of events rather than bumbling along behind them as he has done for so long?

The large-scale loss of life that took place was the proverbial accident that had been waiting to happen

As a long-time close observer of this issue, the most likely way for things to pan out given the personalities of the key players involved strikes me as short-term improvement followed by the onset of sharp further deterioration next spring.

The French authorities have clearly been chastened, especially given reports in recent days of their police standing by and watching migrants put to sea, and the fact that these drownings occurred so close to the coast of France.

Our beleaguered Home Secretary Priti Patel has meanwhile shown a repeated readiness to trust in the prospect of joint Anglo-French action making the route unviable. And Johnson himself has relied on the idea of this being a nut that can only be cracked if France does far more.

We can expect genuine close cooperation between the two countries in the immediate aftermath of this tragedy. Combined with the onset of winter weather and choppier seas, it would be surprising if this did not reduce the volume of crossings substantially.

Yet if Johnson and Patel rely on these factors carrying on indefinitely they will sleepwalk into an even worse phase of the crisis next spring. Then a series of disputes between France and the UK will feature heavily in the French presidential election, giving president Macron a strong incentive to use fair means and foul to put pressure on the Johnson regime. Better weather and the arrival of hundreds of larger inflatables believed to be under manufacture in Turkey could see the scale of crossings explode.

There is another way ahead, but it would require from Johnson the kind of resilience, focus and readiness to fly through establishment flak that he has not displayed since winning the epic battle for Brexit in late 2019. It is not Labour’s solution of creating safe passage for the young men who make their way to the coast of France. That would simply create an enormous new pull factor and ultimately prove the wisdom of Milton Friedman’s observation that a country can have a welfare state or open borders, but it cannot have both.

No, the way forward is to implement a policy that Australian prime minister Scott Morrison once described as ‘taking the sugar off the table’. In the present context this means moving to a system of standard offshore processing of asylum applicants who land illegally with a heavy presumption towards ultimately turning them down.

Doing so may require the UK withdrawing from one or more of the following: the 1951 Geneva Refugee Convention, the European Convention of Human Rights, the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights and the 2018 Global Compact for Migration. Our own Human Rights Act may also need substantial amendment. Justice Secretary Dominic Raab will be well placed to advise the PM on necessary steps.

Such action would no doubt see a wave of liberal establishment outrage unleashed, with the left and its media cheerleaders seeking to portray the UK as a pariah state and Johnson as leading a renegade regime. But if it sounds draconian or unconscionable then consider this quote:

‘On asylum, a Conservative Government will not allow outdated and inflexible rules to prevent us shaping a system which is more humane, more likely to improve community relations and better managed. So we will take back powers from Brussels to ensure national control of asylum policy, withdraw from the 1951 Geneva Convention and work for modernised international agreements. Our objective is a system where we take a fixed number of refugees from the UNHCR rather than simply accepting those who are smuggled to our shores. Asylum seekers’ applications will be processed outside Britain.’

That’s what the Conservative manifesto pledged way back in 2005, when Michael Howard QC – a serious and heavyweight lawyer – was party leader. Back then the liberal establishment retained the power to shut down an honest debate on migration and the Howard agenda did not carry the country against Tony Blair.

Since then we have had Brexit, motivated by a heightened desire to take back control of our borders. The UK is no longer restrained by free movement obligations with the EU, but the asylum system remains entangled in a thicket of outdated global agreements.

In this era of immense and growing migratory flows, motivated far more often by materialist considerations than specific acts of persecution, the present arrangements are unsustainable. If Johnson is not the man to take on the immense challenge of defeating a left establishment increasingly hostile to the idea of self-governing nation states and in thrall to the notion of ‘no borders’ he will find Nigel Farage stepping back into politics to smash the Tory poll score once again. And then whoever becomes Tory leader will have to do it anyway. In other words, this is the new Brexit.

Does social media really make us unhappy?

It’s a well-known fact that social media makes you miserable. While Facebook forever abounds with people apparently having a marvellous time, in exotic climes, never without ubiquitous smiles and exclamations of delight, Twitter seems too often awash with malicious imbeciles, who even when they are right, still get on your nerves. At their worst, Facebook makes you hate people you do know; Twitter makes you hate people you don’t.

This, at least, is a popular opinion. And the consensus that social media makes us unhappy and lonely – in that it encourages us to unfavourably and unrealistically compare our lives to those of others – has been repeated this week in a Harvard study published in the journal JAMA Network Open. It links social media use with greater symptoms of depression. For instance, in its survey of 5,000 adults, it found that users of Facebook were 42 per cent more depressed than those who weren’t.

Whether the findings represent causation or correlation is a moot point. Perhaps depressed people are more likely to seek solace in social media, especially since the beginning of last year, when many began to spend more time alone at home, or have reduced social interaction in the flesh. As Dr Rina Dutta, reader in psychology at King’s College London said in response to the study: ‘social media use could be a marker for emergence of depressive symptoms, particularly in stressful circumstances, like the pandemic.’

As Dr Dutta’s remarks hint, social media is a double-edged sword. Sure, it can induce envy, even if not based on reality. Most people aren’t having a better time of it than you: it just looks that way. But social media can be a source of cheer and great consolation for people who are literally lonely, and for folks who don’t get out that much.

Those of us who have worked from home for years, long before the pandemic, know the therapeutic value of social media. This is particularly true if you are single, live in a small town and rarely socialise.

To me, social media’s curative powers became especially evident earlier this month, during a stay in hospital for a fractured femur. Not only was I unable to work, but owing to Covid restrictions I wasn’t allowed any visitors. There was no television in my ward. Even worse, because I hadn’t brought with me any electronic gadgets, I had no contact with the outside world whatsoever. Only books preserved my sanity.

Fellow patients in beds next to me, most of whom were a couple of decades older, had been better prepared. The majority had at least some device in which to communicate with loved ones face to face or in writing. Undoubtedly, some of them were recounting their experience in hospital through social media posts. I say undoubtedly because I have seen Facebook friends do exactly this over years. Very probably, so have you.

After a couple of bed-ridden days I eventually gained access to social media through the ward’s hitherto unknown computer, and I, too, also began relating my hospital experience. The response raised the spirits. Those ostensibly superficial ‘likes’ and words of support really did cheer me up. Social media inducing depression? Quite the opposite.

Hospitalisation can be a miserable experience mentally, especially if you are left idle, and for older patients, who in mind often suffer more grievously by the experience. Kind words from real or ersatz friends can be a godsend.

In Enlightenment Now (2018), Steven Pinker enthused of the positive possibilities of social media. Before Facebook, keeping in touch with friends or loved ones who lived elsewhere could be a chore or a bore. Social media has had the capacity to keep the erstwhile estranged connected. Pinker writes of the sad, contrasting predicament of all the lonely people in times gone by. ‘Today, after all, Eleanor Rigby and Father McKenzie could be Facebook friends’.

‘Users of social media have more close friends, express more trust in people, feel more supported,’ Pinker argues. ‘Social media users care too much, not too little, about other people, and they empathise with them over them over their troubles rather than envying them their successes.’

The popular psychologist is both right and wrong. Social media envy and FOMO are tenacious emotional beasts, especially when you’re ill or incapacitated. In my demented solitude, those smiling faces seem intent to immisserate me further. In one’s powerless predicament, every achievement by others amplifies Gore Vidal’s famous lament: ‘Every time a friend succeeds, a little something in me dies’.

All the same, social media remains a double-edged sword. It certainly shouldn’t be demonised. Virtual life is actually much the same as real life: it’s full of ups and downs, full of nice and nasty people, who bring us both unhappiness and joy.

Theresa May’s risqué joke

Boris couldn’t make it but fortunately there was one Tory premier at last night’s Spectator parliamentarian awards. Former Prime Minister Theresa May appeared to be having the time of her life at the star-studded bash, rocking a fabulous blue number and waltzing up on stage to win Backbencher of the Year to the strains of ABBA’s ‘Dancing Queen.’ Collecting the award from her former colleague Robert Buckland, May noted drily: ‘Thank you to all those of my parliamentary colleagues who ensured that I was on the backbenches – some of you are here tonight. Looking in no direction…’

But while that line prompted some laughs, it was what followed which really brought the house down. Lauding her constituency, she remarked ‘You must never forget your base’ before revealing she got so excited about the night that ‘I thought about going out to John Lewis and buying myself a new outfit – they do things other than wallpaper you know.’

She praised The Spectator ‘for keeping us on our toes and giving back the furlough money that you took during lockdown,’ spoke highly of the current Speaker Lindsay Hoyle – ‘thank you for not being John Bercow’ – before expressing her warm wishes for her parliamentary peers: ‘thank you to all those Members of Parliament who come up to me and say how much you appreciate my speeches – even if you are all Labour and Liberal Democrat.’ May concluded her well-received speech by saying:

Experience can be overrated. I’m reminded of the story of the couple who got together and they’d both had several partners and on their first night together, he was a little surprised to discover that she was still a virgin and he asked her how was this was. She said, well, she’d had a number of partners, but they had all been politicians. She said the first was a member of the Labour Party and he kept telling me “It could all be so much better!” But he didn’t have a plan of how to do it. The second was a Liberal Democrat and he could never get into the position to do it. And he said “Well, what about the last guy?” And she said, “Well he was a member of the SNP. He just sat on the end of the bed and told me to go independent.”

Strong and stable indeed.

Turkey’s president Erdogan faces his greatest crisis yet

President Erdogan’s aggressive foreign policy is what usually captures the attention of the international media, but it is at home where his biggest troubles now lie. Turkey’s currency, the lira, has tanked, hitting a record low of just over 13 lira to the dollar. Thousands of protesters will hit the streets in the coming days over the country’s turbulent economic situation. Erdogan finds himself embattled.

For now, Erdogan remains defiant. But the figures are brutal: since the beginning of the year, the Turkish lira has lost almost 40 per cent of its value. The minimum wage in Turkey, which was worth $556 (£417) at its highest, is now down to just $255 (£191).

This woeful economic situation has caused a dramatic surge in prices for many basic goods

This woeful economic situation has caused a dramatic surge in prices for many basic goods. Protests are brewing in the streets of Istanbul and Ankara. Is there a way out for Erdogan?

The lira’s dramatic decline has been blamed on the country’s central bank and its three consecutive interest rate cuts in recent months. But Erdogan’s own version of events is somewhat more colourful. Erdogan claimed in a speech this week that Turkey is fighting an ‘economic war of liberation’, that the fall in the value of the country’s currency is the result of manipulations from abroad, and that he has a plan to use the situation to the country’s advantage, making it a strong exporting economy. He has welcomed the drop in the lira’s value as a to boost exports, investments and jobs.

While it’s true that a promise by the United Arab Emirates to invest billions in Turkey halted the downfall yesterday, it seems to be little more than a drop in the ocean. The lira still remains close to a historic low. And despite Erdogan’s claims of outside intervention, the choices that have led to Turkey’s trouble should be placed directly at his party, the AKP’s, door.

Erdogan’s personal interventions in the country’s central bank policy have clearly made matters worse. Turkey’s president has consistently shown that he is ideologically opposed to higher interest rates, and has called them in the past the ‘mother and father of all evil’. His reasoning is that they stave off economic growth. ‘I reject policies that will contract our country, weaken it, condemn our people to unemployment, hunger and poverty,’ he said after a cabinet meeting recently.

The investment promised by UAE is definitely a card he can play with his party’s audience. But will that be enough to convince the country’s civilians, who find their purchasing power dramatically decreased in the space of less than a year?

For now, Erdogan will stick with his plan, perhaps waiting for a breaking point before he has to make a u-turn. Erdogan is a political survivor, an embattled strongman who has seen off coups. But Turkey’s dire economic situation could spell an end to his time in power.

Dear Mary: how can I get out of a Christmas party?

Q. I belong to a fairly intimate private club which is the one reliable oasis of calm and civility that I know of outside my own home. Now an old schoolfriend is pressuring me to propose him for membership (he needs the endorsement of a club member and I am the only one he knows). He is a dear friend who has been kind to me, and I owe him a favour, but he is also extremely jovial and loud and I know he would bring raucous groups of people like himself into the club. This would spoil the atmosphere and end up by making me unpopular with other members. How can I solve this, Mary?

— Name withheld, Edinburgh

A. Agree to write the proposal and hand it over in person to the club secretary. As you are doing this make sure they are concentrating as you muse affectionately about the number of ‘crazy, drunken’ evenings you have spent in your nominee’s company. ‘He’s such a party man!’… Always the last to leave… endless energy!’ and so on. This will warn the committee, in a way that discounts you from being disloyal, and the matter will be out of your hands.

Q. Like many people of a certain age, I am keen on a flattering light, and the fashion for brilliant LED spotlights in ceilings is at odds with this. I find myself quite miserable in the living room of a dear relation, where visitors have every imperfection cruelly highlighted, and feel 101 as a result. I know that if these lights were replaced with angled fittings directed towards the walls, and warm-toned bulbs, we would all visit her more enthusiastically. However, there seems no tactful way to suggest this.

— C.A., London N1

A. Next time, walk in with a present of a tasteful table lamp from Pooky complete with warm-toned bulb. Gush as you arrive that ‘it’s all over the internet’ that LED spotlights can make you feel low-grade anxiety and depression (true) and, since you turned off your own LED lights and bought one of these lamps, you feel much happier. ‘And also more confident because…’ [as you plug it in and switch off the searchlights] ‘…look! One looks so much better with a soft light. You look absolutely beautiful now.’

Q. My husband and I are beginning to receive Christmas party invitations. While grateful for these, we remain cautious about Covid, and don’t want to put our much-awaited family Christmas in jeopardy. Mary, how do we turn these kind invitations down without seeming like killjoys?

— M.P.-W., Chelsea

A. Reply to each one immediately on receipt saying you can’t bear it, but that is the one night you are busy that week. The would-be hosts will assume you will be busy attending another super-spreader — they need not know you will be busy wrapping presents at home.

Nicola Sturgeon’s desperate new misinformation drive

Less than a quarter of Scots believe Scotland is likely to leave the UK within the next five years, according to a new poll. The poll also shows that secession does not command majority support.

As we approach the second anniversary of the start of the pandemic, it seems getting back to normal is more important to most people than the break up of the UK. Managing to holiday abroad over the next two years is likely to be a more popular aim than another referendum.

Seemingly disconnected from that reality though are Scotland’s nationalist parties, which last week produced – in conjunction with the National newspaper and a separatist campaigning organisation called Believe in Scotland – an eight-page tabloid-style pull-out designed to make the case for secession.

Billed as being ‘delivered free to a million homes across Scotland’ before St Andrews day, the publication included articles from senior SNP figures, including Nicola Sturgeon and finance secretary Kate Forbes, and from the Scottish Green party co-head and Scottish government minister Lorna Slater.

Most of the content is low-grade, Farage-esque anti-politics politics, drumming up fears of nasty outside forces doing Scotland down. More alarmingly though, some of the content is either misleading or outright misinformation.

Take Kate Forbes’ contribution, for instance. In her column she argues Scotland is a wealthy country that ‘more than pays its way’ and ‘generates enough tax to cover all devolved spending – despite what opponents of independence would mislead you to believe’.

The first statement is clearly designed to give readers the impression Scotland is a net fiscal contributor to the UK. This is not the case. The Scottish government’s latest official statistics show Scotland’s notional deficit for 2020-21 was 22.4 per cent of Scottish GDP, or £36.3 billion. Pre-pandemic (2019-20), the deficit was 8.6 per cent of GDP, or £15 billion. Of course, at the UK level a real deficit is being financed via large-scale borrowing by the Treasury. When Scotland’s population share of that borrowing is accounted for, the numbers show Scotland benefitting from a net fiscal transfer of around £12 billion per year.

Forbes’ second statement is also misleading. By taking only a selection of state spending, and asserting that Scotland’s current tax revenues cover these areas, you can imply that this demonstrates that a newly-separated Scotland would be able to fund itself. All it really shows, however, is that Scottish taxes alone only pay for a fraction of Scotland’s spending needs.

This is not to say Scotland’s economy is weak. The Scottish economy is more than capable of generating healthy tax revenues per head. But Scotland has such a large deficit because it is a big spender of state money (government spending in or on behalf of Scotland was around 12 per cent higher than for the UK as a whole pre-pandemic).

The pull-out also repeats a falsehood deployed by Nicola Sturgeon recently at Cop26. It states: ‘Ninety-seven per cent of our electricity now comes from renewables’.

This is not true. In 2020, 56 per cent of the electricity consumed in Scotland came from renewable sources.

In a briefing to international journalists this month, Sturgeon, speaking about threats from Russia, said: ‘The problem of misinformation in our social media and therefore in our wider political debates is a very real one. I think all democratic politicians should be very vigilant about that and very willing to call that out.’

Just a few days later she was directing her activists to deliver, to a million homes across Scotland, misleading propaganda that can only fairly be described as misinformation.

If there was any possibility of another referendum happening in the next few years then this would be a real concern – real enough for any UK government to insist the current nationalist-dominated Holyrood cannot be trusted to implement a fair plebiscite. But the point of the exercise is clearly not to win over new converts in the build-up to a referendum. These days even Sturgeon must have to stifle a snigger when she talks about another referendum happening before the end of 2023.

Instead, the target audience for this propaganda are the true believers, whom the SNP now have a fairly well-established strategy of serially deluding. That is why the language used throughout is aggressive and Farage-esque, and why it came free with a copy of the nationalist fanzine newspaper the National. This is not a pamphlet designed to reach out to the persuadable – it’s a comfort blanket for the faithful.

Those of a heretical disposition in Scotland can take some solace in that. Scots might have to endure a winter of misinformation, but it signals only desperation from the SNP. The nationalists aren’t on the march. They are sitting in a bunker talking to themselves.

Peng Shuai and the return of the concubine

A high-flying Chinese businessman once told me his secret to happiness: ‘Before a man is 35, women are tools; after 35, women are toys.’ It worked for him. He married an educated woman from a good family who helped him climb the career ladder; but once established in his career, he began seeking more exciting female company.

I’ve been thinking about that man since the story of the Chinese tennis player Peng Shuai broke. Peng detailed a three-year affair she had with the retired vice premier Zhang Gaoli, 40 years her senior. During the good times, they would ‘talk for hours, play chess, play tennis no end… our personalities fitted so well’. But when he got bored, he ‘disappeared’ and ‘tossed me aside’, she wrote on Weibo.

Chinese social media was treated to an insider view of the salacious lifestyles communist officials still lead. This was no ordinary affair. Peng says it started when Zhang forced her to have sex after they played tennis — ‘that afternoon I cried and didn’t agree at first’ — but she stayed for dinner, and Zhang kept up the pressure. ‘Yes, we had sex. Emotions are complicated, hard to put into words. From that day on, I decided to open my heart [to him].’ A far cry from your average ambitious mistress, Peng seems to be someone who was abused, groomed and abandoned. She was at pains to say she didn’t take a penny from Zhang.

The #MeToo scandal hit China’s celebrity world earlier this year with the arrest of the actor Kris Wu, a Chinese R. Kelly. Beijing leapt on the bandwagon when pop stars were the ones being accused. What would the Chinese Communist party do once the scrutiny turned on one of its own?

Censor, of course. It wasn’t long before Peng’s post, account and all references to the statement were scrubbed clean from social media. For a time even the word ‘tennis’ was censored as a search term. Then came radio silence from Peng — until last week. Presumably in response to growing international pressure (the Women’s Tennis Association has threatened to cancel all China events, and tennis stars from Serena Williams to Novak Djokovic rallied around the hashtag #WhereIsPengShuai), a series of ‘proof of life’ videos, photos and emails of Peng in public have surfaced. But these have all come from state media sources, such as the Global Times, leading to questions about how scripted they are. One video even starts with a director off-screen cueing Peng’s coach to start talking. In the coming weeks, state media outlets are likely to continue disseminating these staged appearances. It allows the Chinese government to present interest in Peng’s story as ‘western media hysteria’. But while no one is quite sure where Peng is, she has revealed a rot at the highest level of the party, a dangerous thing to do in Xi’s China.

It’s a story as old as sin. In China’s imperial past, men were entitled to have a wife and as many (legally inferior) concubines as they could afford. Emperors would have hundreds, and even now a mistress is referred to as a ‘concubine’; a wife is an ‘empress’. Polygamy was officially abolished in 1949 with the communist takeover, but the mindset didn’t change much.

Peng Shuai’s story has highlighted the salacious lifestyles that communist officials still lead

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, when China started to get very rich again, it became fashionable for men of a certain stature to have a mistress. Young, pretty, often uneducated and poor girls offered intimate company, yet some men wanted more: the former head of propaganda at Chongqing, for instance, required his lovers to have a bachelor’s degree. The more generous men gave their mistresses pocket money, cars and even flats. One neighbourhood in Shenzhen was dubbed ‘concubine village’ in the 1990s, reportedly being home to 50,000 mistresses. Their lovers, mostly businessmen in Hong Kong, were a short train ride away, and much wealthier than anyone in the mainland. One Jiangsu party official had 146 mistresses, detailing them all in a sordid little notebook. The former head of the Nanjing Dairy Industry Group (also known as ‘the Milk King’) put it well when he said: ‘What official at my seniority doesn’t have a few lovers? This isn’t just a biological need, it’s more crucially a status symbol. How else will you get the respect of others?’

For a time, stories of such philandering made the news, especially when officials got done for corruption (the two tended to go hand in hand, as the mistress lifestyle can get expensive — one disgraced Shenzhen official’s harem cost him almost £3,000 a day). Then came Xi’s 2012 anti-corruption campaign: a root-and-branch operation that indicted 100,000 officials within a few years. Almost all those arrested were having some kind of extramarital affair, according to Renmin University. After the purge, there was silence on the romantic lives of high-ranking officials. Had it scared politicians into monogamy? Peng’s story suggests otherwise.

Most mistresses don’t have such harrowing stories, but what is a status symbol for the men is a mark of shame for the women involved. Nobody wants their daughter to be a mistress. It’s telling that Peng announced her affair with the words: ‘I admit I’m not a good girl.’ Grisly videos circulate online of mistresses getting their comeuppance as angry wives enlist family members to beat and publicly humiliate them.

More often, the wives can only turn a blind eye. My businessman friend was upfront with his wife, telling her upon proposing that she should never expect him to be faithful to her. She agreed to marry him on three conditions: that he would never bring a mistress home, that he would not have children with his lovers, and that he would not financially ruin his family. Zhang’s wife seems to have gone one step further and ‘stood guard’ while Zhang forced himself on Peng that first time. Peng compares her to ‘the empress in Zhen Huan Zhuan’ (a TV drama about the palace intrigues of a Qing dynasty harem), saying the wife shot snide comments at her when Zhang wasn’t around.

Under Xi, the CCP has made a big show of abandoning its old reputation for corruption and extravagance. But Peng Shuai’s story — and the way the party quickly closed ranks — raises the question of how much decadence still goes on beneath the surface. And outside of politics, successful men like my businessman friend continue their lifestyles as their wives ignore the goings-on. China hasn’t yet said farewell to the concubine.

Worth seeing for Lady Gaga but little else: House of Gucci reviewed

Ridley Scott’s House of Gucci has been much anticipated. The cast is stellar. It’s based on a luscious, true story (so juicy) featuring vicious family infighting and culminating in a murder. I was thinking Succession, but with luxury leather goods and the hiring of a hit man. It can’t miss, I was thinking. Except it can. Not entirely. It has its moments. But the middle act drags (it’s two hours and 40 minutes long) and also the decision to have the English-speaking cast a-speak-a in Italian accents may not have been the wisest one. There were many times I thought Gino D’Acampo was in the room-a.

This stars Lady Gaga and she really stars. Or, to put it another way, she is fascinating to watch, the best thing in this by a country mile, and manages to disappear inside her character in a way no one else in the cast does. She plays Patrizia Reggiani, the girl from the wrong side of the tracks (her father ran a trucking business) who, in 1970, meets Maurizio Gucci (Adam Driver), heir to the Italian fashion empire, at a party and is determined to have him. But also they do fall in love. Maurizio’s father (Jeremy Irons, who shouldn’t be made-a to speak in an Italian accent but is, and does so when he remembers) is dead set against their marriage and breaks off all contact. But Uncle Aldo (Al Pacino, totally chewing the scenery) is more friendly and wants Maurizio to become more involved in the business given that his own son Paolo (Jared Leto) is a useless oaf. Paulo is written as a comic character, and Leto plays it for comedy, which made these scenes not only feel as if they were from a different film entirely but also tone deaf somehow. (I later looked up Paolo and my God, what a tragedy. Laughing at him seemed off and it is.)

Patrizia is certainly more ambitious for Maurizio than Maurizio is for himself and soon he’s embroiled in the family business which, at this point, makes its own knock-offs. (I found such details interesting, particularly as there is very little insight into what they are selling otherwise.) But the central driving force of the film is the marriage, and when the narrative sticks to that, this does command your full attention.

However, midway through Patrizia and Maurizio are forced to take a back seat while the film focuses on matters of tax evasion and all kinds of boardroom shenanigans, and loses any pace. This is when I found myself longing for Ryan Murphy (creator of American Crime Story and that series about Versace), who, unlike Scott, knows how to keep kitsch-camp energy running at a high and how to avoid falling into plodding biopic territory. (And-then-this-happened, and-then-this-happened…) By the time we return to Patrizia the marriage has gone sour, and Maurizio wants out, but you don’t really see the process of the souring or the build-up of the jealousy, bitterness and resentment that would lead her to hire a hitman. (That’s not a spoiler, right? You know she’s the ‘Black Widow’, right?)

There are a few scenes that are absolute stand-outs. There is one in a chalet in St Moritz and also there’s Patrizia’s last-ditch attempt to win her husband back with a photo album. That’s the only time I ever felt anything. Otherwise, the film does not ask you to care about anyone and there is scant character development. Driver, as Maurizio, seems largely absent but maybe that is intentional. Meanwhile, the Gucci residences are spectacular, as are the clothes, which somehow look both cheap and expensive. Is that Gucci? I don’t know. I am solely House of Uniqlo. In short, this isn’t a bad film, and it’s probably worth seeing for Lady Gaga alone, but also it’s not a great one. Or ‘great-a-one-a’, I should say.

Lockdown creations: the best of the year’s cookery books reviewed

‘I may, one day, stop making notes and writing down recipes,’ Nigel Slater says in A Cook’s Book (Fourth Estate, £30). Please don’t. This is his 16th book and his writing feels as fresh as it ever did. I remember cutting out his recipes from Elle Magazine three decades ago, and I do not believe he has ever put pen to paper without wanting his ideas to work for others. Mountains of good food must have been set on tables and shared by people as a result, because Slater is a master of his trade. ‘A recipe must work. Otherwise, what’s the point?’ he says.

Quite; though a cynic would add that the genre is full of recipes that either don’t work or never quite resemble the glories of a book’s images. A Cook’s Book is a gift to a novice, as well as a reminder to a seasoned, even tired, cook of what it is all about. The practice of cookery is like that of any pursuit: the more you do it, the better you will become, and the more able to adapt and problem-solve — as long as you do not give up.

Yet every enthusiastic, dedicated home cook reaches a point when they feel it would be so nice to hang up the apron. You have cooked for fussy partners, picky children, the person who rings up mid-afternoon on the day of the dinner to tell you they’re vegan-ish… You have had enough. What you need is a booster jab of inspiration: a reminder of why you love cooking. This is where Slater comes in, with green Thai bubble-and- squeak fritters; griddled asparagus with buttery lemon mash — a brilliant dish in which the potato reflects the flavour of the asparagus like a disco ball; or a plum and blackcurrant ‘free-form’ pie — an amoeba-cum-tart that an amateur cannot fail at.

Even the most dedicated home cooks can tire, and need to be reminded of why they love cooking

It is impossible not to read this season’s books without a sense of how they were created in a pandemic. Slater, in his basement kitchen, missing not a single detail of his surroundings, tools and craft — like a lifer in his cell. Then, there is the actor Stanley Tucci, normally an in-demand travelling player for whom an enforced period at home with his wife and family must have been the greatest of extravagances. He celebrates by writing a memoir, Taste: My Life Through Food (Fig Tree, £20). I read it through the night. Food memoirs are tough to pull off, but Tucci’s has the essentials: honesty, humour, humility and real acquired knowledge.

He admits to an all-American beginning of peanut butter-and-jelly sandwiches, but also his busy parents’ relaxed Friday night meatball feasts. Food met his work when he directed and starred in the film Big Night, a drama about two Italian chef-patrons. Later, he played the part of the (literally) towering American food writer Julia Child’s shorter husband Paul in Nora Ephron’s Julie & Julia. Meryl Streep played Julia, and I will leave for you his gruellingly funny story of the two of them not enjoying France’s smelliest sausage, andouillette, on the ensuing press tour.

Gripping, however, is the section on how grim location catering can be. Fuel for actors apparently tends to be just that: sausage sandwiches about sums it up. For all Tucci’s success, he has endured a great deal: bereavement and a dangerous, cruel cancer — of the tongue; but then joy with his second wife, Felicity. He’s only 60, for heaven’s sake. I want the sequel.

The catering and restaurant business suffered greatly in the pandemic, and perhaps have not been lauded enough for all they did while their customers were locked out. The industry supplied hundreds of thousands of meals to NHS staff, but for many it was a case of sitting tight, hoping their businesses would survive. Shona Pollock, famous for catering weddings, took the time to publish a delightful collection of recipes, Muddy Spuds: Rustic Recipes From My Kitchen (shonapollock.co.uk, £25). A long way from the canapés she would normally offer brides and grooms, this is the kind of home cooking most of us need. Recipes range from retro favourites such as a workable beef stroganoff and a chocolate roulade to pretty, global salads, tarts, curries and roasts.

Yotam Ottolenghi became an often-heard spokesman for beleaguered restaurateurs during lockdown while developing a series of notebooks in his workshop under a railway arch in north London. The first of the ‘Test Kitchen’ series, Shelf Love (Ebury Press, £25), has a bright, cleanable soft cover and comes filled with some of the most appetising dishes ever put together using a base of larder foods. I’ll definitely make his (and his fellow writer Noor Marad’s) greens and chermoula potato pie and the zatar parathas, greatly helped by step-by-step photography — something I wish more cookbooks would feature. While good food writing speaks volumes, novice cooks desperately need useful images. I look forward to the next book in the series.

Mandy Yin abandoned a career in the law to open Sambal Shiok in the Holloway Road, devoted to her roots in Malaysia and its hotchpotch of cooking styles. The restaurant is famous for its true versions of laksa. There is the type many of us know, with curry-scented coconut milk poured over noodles, tofu buns and crunchy vegetables; but I’d buy her Sambal Shiok (Quadrille, £25) alone for the Penang Assam Laksa, a fruity, sour soup perfumed with lemon grass, tamarind, galangal and fresh mackerel. The broth is ladled over rice noodles, fresh cucumber and pineapple. Prepare to line up an alarming number of ingredients for this one, but it will make your senses sparkle. Other recipes include curries, stir-fries and street food snacks. But the book is also a good read: Yin’s personal, lawyer-to-laksa story is intriguing.

The progress of the Michelin-starred chef Ollie Dabbous could not be more different. He trained in some of the world’s best restaurants and now heads his own kitchen at the acclaimed Hide in Mayfair. Normally I greet such a chef’s book on home cooking with a sceptical sniff. But Essential (Bloomsbury, £30) is another lockdown creation and, becalmed at home, Dabbous has put himself in our shoes. He offers pretty versions of simple dishes. For an easy supper there’s a gram flour pancake with garlic shrimps, fennel and parsley; the filling for his own version of sausage rolls has the brilliant addition of Worcester sauce, apple and mustard, and he does a wonderfully light version of treacle tart using white miso paste. It’s the good ideas that count: the decoration is, as this thoughtful chef suggests, optional.

Finally, seeing that Christmas is unlikely to be cancelled this year, there is At Christmas We Feast: Festive Food Through the Ages by Annie Gray (Profile Books, £12.99). Recounting the origins of pigs in blankets (American) beats fighting with members of the family. Christmas unlocked? I can’t wait.

Guilt-free hilarity: Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike at Charing Cross Theatre reviewed

World-class sex bomb Janie Dee stars in a fabulously silly revival of the American comedy Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike. She plays a movie diva, Masha, who loves to flaunt her wealth in front of her mousy sister and bookish brother. Striding into the family home with her long hair flying and her scarlet lips curling, she narrows her eyes and flings shafts of desire in all directions. Then she arches her neck and tosses back her head to give her bust an extra half-inch of uplift. A stunning display.

The show is about three middle-aged siblings whose over-intellectual parents named them after characters in Chekhov plays. Vanya is a hopeless dreamer. Sonia pines for sexual attention but can’t compete with Masha whose dazzling looks are fading and whose young boyfriend, Spike, has a wandering eye. The characters are invited to a fancy-dress party and bossy Masha decides to go as Snow White. Her siblings, she insists, must dress as dwarfs. She drags along an ambitious young thesp, Nina, who dotes on Masha and covets her fame and success.

There’s a full set of victims and survivors but they want us to feel good about life

It sounds a little contrived but the ramshackle structure is cleverly handled by the writer, Christopher Durang, who knows how to use sex to keep a story moving. And he maintains a good strike rate of gags. In places it’s as corny as hell and the Chekhov references are laid on with a trowel but the spirit is capricious and fun-loving, never earnest. Director Walter Bobbie knows exactly what he wants from this caper — to take the audience on a wild two-hour ride.

The six characters also embody many of the hot-button issues favoured by progressive theatres: Vanya is gay, Sonia is adopted, Spike is bi-curious, Masha is a sex addict, Nina is mixed-race and the maid, Cassandra, is mentally unstable. That’s a full set of victims and survivors. But these misfits don’t thrust their pain down the viewer’s throat or beg for people to ‘reach out’ to them. They want us to feel good about life. The result is a night of guilt-free hilarity.

The Royal Court is also examining issues that trouble the liberal mindset. Its latest drama, Rare Earth Mettle, looks at the exploitation of the world’s poor by evil capitalists. This vapid, sprawling yarn could do with a dose of sex as well. No character has any romantic yearnings at all, and the story feels as insipid as soggy tobacco.

The script opens with America’s stupidest billionaire, Henry Finn, discovering a dried-up lake in Bolivia where 70 per cent of the world’s lithium supplies lie buried. He tries to buy the lot for $10,000 from a surly peasant who hates Americans. Meanwhile in London another wicked schemer, Dr Anna, wants to grab the seam of lithium to solve the world’s mental-health crisis. She’s discovered a miracle cure that she plans to test by dumping lithium into the water supply of Stockport which — she quips — has more mental-health problems than anywhere else in Britain. (Obviously the ‘half-witted northerner’ joke is a favourite at the Court.)

Dr Anna is played as a heartless Home Counties hag by Genevieve O’Reilly who gives her a pre-war Celia Johnson accent. The word ‘probity’ gets five syllables —‘praya-buh-tier’. She sounds posher than the Queen. The storyline rattles through a predictable list of crimes as Dr Anna and Henry Finn travel the world oppressing the weak, grabbing their assets and silencing dissenters with huge bribes. But something unexpected emerges. The dominant characters have all the wealth and authority because the script appears to regard them as naturally gifted. The reason they have the expertise to build battery-powered cars and find cures for ghastly diseases is that they’re smarter than their rivals.

The Bolivians try to pull a fast one by inventing a fictional new tribe but they ask a white ethnographer to validate their claim. What a bizarre idea. Do Anglo-Saxons know more about Bolivia than Bolivians? The play also assumes that no one in South America speaks a word of English unless they’ve graduated from a western university. The whole drama is stuck in the 19th century. Even a sick Bolivian teenager tells Dr Anna about the inevitable triumph of the West. ‘I don’t think you’ll ever run out of ideas,’ she lisps, ‘especially where you’re from.’

To be fair, this three-hour play feels as indigestible as the policy lecture it aspires to be. The Court long ago gave up operating as a theatre and decided to become a think tank. Perhaps this latest flop will convince the entire panel of directors to resign — apart from the publicists who are great fun and who bake lovely handmade sausage rolls for the critics on press night. Their toasty bite-sized treats are the only competent service this embarrassing dump provides. Could it reopen as a patisserie?

His final paintings are like Jackson Pollocks: RA’s Late Constable reviewed

On 13 July 1815, John Constable wrote to his fiancée, Maria Bicknell, about this and that. Interspersed with a discussion of the fine weather and the lack of village gossip, he added a disclaimer on the subject posterity would most like to hear about: his art. ‘You know that I do not like to talk of what I am about in painting (I am such a conjuror).’

Perhaps by that he meant he did not like to give away how he did his tricks. As Late Constable, the magnificent exhibition currently at the Royal Academy, makes clear, he was a true magician with paintbrush and palette. Before your eye he performs astonishing transformations. Take, for example, the little oil sketch ‘Rainstorm over the Sea’, c.1824–8.

It’s a picture of a sudden squall. A dark, mulberry-coloured cloud has appeared above the waves off Brighton beach (which are themselves a steely blue). Out to sea, the deluge is already falling in great slooshing curtains. Even the passage of the drops, cascading through the air, seems to be visible.

This show makes clear that Constable was a true magician with paintbrush and palette

Constable has conveyed all this with half a dozen broad, brusque brush strokes, scything down his little picture. They remain obviously the marks of a wide brush loaded with thin pigment, the grooves left by the bristles undisguised. The absolutely remarkable thing is that Constable manages to make you see both at the same time: smears of paint which are, simultaneously, exactly like a downpour seen from a distance.

He performed that kind of miracle on a regular basis, as Late Constable makes clear. Even those who think they know his work intimately are likely to find it full of surprises. The fact is, we don’t know the art of this apparently familiar master all that well after all. The curator, Anne Lyles, makes the case that in the last 12 years of his life Constable (1776–1837) entered an extraordinary final phase as an artist, a period of unprecedented freedom, mastery and (often) looseness of touch.

Naturally, he was not thanked for it by most of the London critics and public. They admired smoothness and blandness in surface — what was known as ‘finish’. ‘My execution annoys most of them,’ the artist wrote to his friend Archdeacon Fisher. The white highlights he used to represent sparkling sunlight came in for particular denigration, being lampooned as ‘spotting’, ‘snow’ or ‘whitewash falling from a ceiling’.

In his later years, Turner often came in for equally rough treatment for his ‘extravagances’. The fate of the critics concerned, such as Constable’s tormentor Edward Dubois whose eyes ‘sparkled with wit and malice’, was to be remembered solely as the fool who insulted a great artist. But at the time such attitudes had an effect. Constable confessed to Fisher that he had applied an unusual quantity of ‘eye-salve’ to ‘The Cornfield’ (1826) out of a desire to sell it.

This raises the question of what he really wanted to do when he didn’t have to soothe the eyes the Regency art world. Are the wildest pictures the ones he liked the best (rather than the generally tamer ones he actually exhibited)? I certainly love them.

‘A Farmhouse near the Water’s Edge (“On the Stour”)’ (c.1834–6), for example, brings much later painters to mind: Leon Kossoff, Frank Auerbach, even Jackson Pollock. The subject is extremely ordinary: a tree on a short stretch of riverbank, with a humble house behind. But it becomes the centre of a swirling, flickering vortex in which leaves, clouds, water and light all play a part.

Just as amazing, to my mind, are many of Constable’s late works on paper. ‘View on the Stour: Dedham Church in the distance’, c.1836, does everything that the oils do with just a few puddles, sweeps and blots of brownish-black ink. It’s close to abstract but again everything’s there: church tower, burgeoning vegetation, majestic cloudscape (Constable famously said that the sky was ‘the chief organ of sentiment’ in a picture, but with him it is specifically the rolling, swirling clouds).

To later artists, how Constable painted — that ‘conjuring’ with a brush — was quite as important as what he depicted. This daring virtuosity was a large part of what other painters such as Delacroix, Géricault and Lucian Freud admired. The last of those once described ‘The Leaping Horse’ of 1825 (three sketches of which plus the final version are on show at the RA), as ‘the greatest painting in the world’.

Constable’s concentration on the every-day was influential too. Auerbach once extolled the audacity of his humble subject-matter. It was, he argued, ‘at least as shocking as Gilbert & George’s is: barges, rotting stumps. This was a person blatantly shoving rubbish into our faces and making grand, Michelangelo-esque compositions of it’ — which is not the standard take on ‘The Hay Wain’.

Right from the start the British have got Constable wrong. They’ve admired him as an exponent of English cosiness and failed to appreciate his painterly brilliance. This marvellous exhibition should open many eyes.

‘Immigration is war’: an interview with Éric Zemmour

Éric Zemmour looks down at a copy of The Spectator and cocks his eyebrows at the unflattering cartoon of him on the cover. He decides he doesn’t care. ‘It takes a lot to offend me, you know,’ he says. He then leafs through the magazine making polite and appreciative noises. ‘Ah, Doooglas Murray!’ he exclaims. ‘I like Doooglas Murray very much. We’ve exchanged ideas.’

Zemmour is in London as part of his still undeclared campaign to be the next president of France — to curry favour with and raise money from the many French voters who live in the capital. But the British Establishment has given him a cold reception. Mayor Sadiq Khan said he wasn’t welcome. The Royal Institution cancelled his event. The government ordered Conservatives to call off meetings with him. That could be because Boris Johnson hopes to repair badly damaged relations with Emmanuel Macron, the man Zemmour wants to eject from the Élysée Palace. Or it could just be that Mr Z is considered so right wing as to be toxic.

Team Zemmour argue that the Tories have missed a trick. A President Zemmour would be far less antagonistic to Brexit Britain than President Macron. Zemmour is officially against ‘Frexit’, yet he is complimentary, even a touch romantic about Britain’s decision to leave the European Union. ‘The conservative elites, at least some of them, are proud to have respected the choice of the British people, unlike the French political elites,’ he says, speaking in French because his English is limited. He compares Brexit with France’s referendum in 2005, when the French said ‘non’ to the European Constitution, only to be ignored. ‘That was disgraceful. I find the behaviour of the British elites much more noble.’

He argues that Emmanuel Macron and the ‘Brussels technocracy’ have made a ‘fundamental mistake’ in their eagerness to make Britain pay for betraying Europe. ‘They want to persuade, I don’t know, Hungary, other countries, or even France, who might be tempted to leave the European Union and break up their ideal. I think this ideological and moralistic approach — “It’s not right! We’re going to punish you like a child!” — is not appropriate. First of all because it is counterproductive. It creates ill will, as we see with the fishing story. Furthermore, the choice of the British must be respected. It’s democratic.’

He’s quick to add that he finds it ‘cruel’ of Britain to have withheld licences from French fisherman over waters they’ve trawled for centuries. ‘I don’t think this “fair”, as you like to say in England,’ he says, amusing himself with the quaint Anglo–Saxonness of the notion. ‘I find it “unfair”.’ He also blames Macron for ‘negotiating very badly’ and throws in a swipe at Michel Barnier, the chief Brexit negotiator and another candidate in the 2022 French presidential election: ‘He showed his limitations there. It’s incredible that he left the issue hanging in the air and did not deal with it.’

Fishing is one problem; cross-Channel illegal immigration quite another. What would President Zemmour do to stop the growing number of migrant boats from France arriving on Britain’s shores? ‘I’ll tell you what: if I were president, they would not arrive in Calais.’ He says the Le Touquet agreement, through which Britain pays to support French border checkpoints, is ‘disrespectful’ to France. ‘We’re not a third-world country. I don’t understand why French governments accepted this. On the other hand, these people… should not enter France. We should do every-thing possible to dissuade them. I would expel these people and I would suppress all social aid so that they would not be tempted to come any more… I saw your Home Secretary say — and she is absolutely right — that France should better control its border.’

He’s officially against ‘Frexit’, yet he is a touch romantic about Britain’s decision to leave the European Union

Frontex, the EU’s border agency, is ‘in reality useless,’ he says. ‘A few hundred agents who cannot control anything and when the poor fellows want to do their job and turn the migrants back, the European parliament and the Commission in Brussels accuse them of brutality.’ He applauds Poland’s attempt to build a wall on the Belarusian border. ‘They should be helped. Contrary to the Commission in Brussels, I think that walls should be built wherever possible.’

We’re now on to the issue that drives Zemmour’s political mission and fuels his incendiary campaign. ‘Immigration is war,’ he says, hitting his rhetorical stride. ‘They want to invade our European countries. That’s all. It’s nothing else. It’s war.’

‘Do you think Macron is deploying migrants as a weapon of war?’ I ask, fishing without a licence for a newsline.

‘I don’t think he has such malicious intent,’ he replies. ‘He’s not Erdogan. No, you mustn’t exaggerate. I just think that he is, how can I put, ideologically in favour of immigration.’

Zemmour has for some years been a leading public intellectual in France, a popular historian as well as a television provocateur and one of the country’s most famous journalists. He litters his speech with great quotes: ‘As Victor Hugo said… As Voltaire said… As Chateaubriand said…’ He speaks in newspaper columns: press his opinion button and he’s off. His eloquence is almost hypnotic.

Macron, he goes on, is gripped by ‘an individualistic ideology. He thinks every individual is basically the same and can live everywhere. Of course, he will enforce rules here and there, but fundamentally…the existence of peoples to him seems outdated.’

Does he blame the economic liberalism of Thatcher and Reagan for the excessive individualism to which Macron subscribes? ‘I wouldn’t say that,’ he replies. ‘It’s more a deviation from Christian humanism. As Chesterton said: “It’s Christian virtues gone mad.”’

Western societies, Zemmour suggests, have ‘simply forgotten that in Christian humanism there is indeed the respect for the individual but that is rooted in a culture, a religion, a people, a land… [today] we have the individual who is sacred, very well, but who is completely isolated from his people, his historical context, his customs. You see it is believed that individuals are interchangeable, that they are only consumers. It’s an economistic view that I don’t share. I think that people are first of all a product of their culture, their people, their customs.’

Zemmour prefers the English word ‘globalisation’ to the French ‘mondialisation’ to describe this process. ‘It’s an alliance of left and right,’ he says. ‘Above all it is cowardice.’ By that he means that European leaders have been weak in refusing to tackle the social and political ills concomitant with globalisation. ‘For 40 years they’ve been afraid to confront the politically correct, afraid of riots in suburbs, afraid of being seen in a bad light by the media, afraid of not obeying the judges.’

For Zemmour, the most craven expression of this hyper-individualism is militant political correctness — ‘le wokeisme’. He calls it ‘hypersensitivity to the rights of the individual, a generalised offensive against French and western culture, against the white heterosexual man. These people want above all to make the French and all westerners feel guilty, ashamed of their history, so that they amputate themselves, destroy themselves, abandon their culture, their civilisation, simply so that they no longer feel guilty.’

This wokeness, he argues, is a kind of Trojan horse for the Islamification of formerly Christian nations. ‘It is by destroying our cultures, our history, that they make a clean sweep of all that and allow a foreign culture, history and civilisation to come and replace it.’

Such talk — echoing as it does ‘the great replacement theory’ of Renaud Camus — causes consternation in progressive circles. Somebody, probably David Aaronovitch, will no doubt accuse The Spectator of giving a platform to nativism or white supremacism merely by speaking to him. Yet Zemmour is utterly unabashed about his views and he’s currently second or third in the presidential election polls.

Might his preoccupations with national characteristics, the greatness of French literature and the collapse of western civilisation have something to do with the fact that he is himself an immigrant child? His parents were Berber Jews from Algeria. His grandfather spoke better Arabic than French. His father drove an ambulance.

‘What my family has done in terms of assimilating French culture should be an example,’ he says, proudly. ‘I am a product of French colonialisation. I am not one of these people who condemn the French coloniser. I say thank you.

‘I think that nations are the pinnacle of civilisation. I like the differences of nations. I like the fact that the English are very different from the French, just as they are very different from the Germans. The great tragedy of globalisation is that previously there were nations that were different to each other and within each nation there was a great cultural coherence.’

His press officer has been frantically gesturing for us to wrap up, so we do. Zemmour has a Eurostar to catch. He’s spent two days in London and his team seem stressed and exhausted. They just want to get back to la belle France.

Cheap schlock has now become expensive schlock: Adele’s 30 reviewed

Grade: C

The problem I have is that I thought she was pretty awful before — when she was just fat and from Tottenham. Now that she has been marinated in SoCal for six years, she seems to have become even worse: a kind of Meghan Markle with a larynx. It was cheap schlock all the way back then; it’s expensive schlock now — that’s the only difference.

This is her divorce album, her ‘Hollywood’ album, her mature album, her BRAVE album according to her adoring… critics is obviously the wrong word. OK, it starts off with words — ‘I’ll be taking flowers to the cemetery of my heart’ — on the song ‘Strangers By Nature’. If that doesn’t make you blush embarrassedly for her, then what will?

That song, much as one or two others, is Adele pretending she is Nat King Cole and consequently we are intermittently euthanised by cocktail piano and eminently predictable faux-jazz chord changes.

Elsewhere, when she wants to get modern, she puts that accent on common to all English female singers now strutting their stuff, which is really a bad attempt at being black.

There is, here and there, ungainly autotuning — which I hadn’t expected — and the unconvincing aping of Amy Winehouse (on the half-decent ‘Cry Your Heart Out’, which, frankly, I had). ‘Oh My God’ is as awful as the title suggests, but there is a certain lilt to the 1950s pastiche of ‘Night Parking’.

We have always had landfill MOR dominating the pop charts. The difference is we never before afforded it importance or moment. Why, then, do we now? Why the fuss?

When did Christmas adverts become so unbearable?

When I was young, I dated a man who wasn’t in advertising, but had lots of friends who were. Because I am witty, at some point during dinner — usually when dessert was being laid out with a platinum credit card — one of them would say: ‘Have you ever thought of working in advertising?’ I remember feeling real indignation, like someone had spat in my spritzer. I don’t care that Salman ‘Naughty, but nice’ Rushdie and Fay ‘Go to work on an egg’ Weldon started out that way; I had no intention of ending up in such a venal profession. So intense were my feelings that when, as a Bright Young Thing in the 1980s, I was asked to be one of the fresh faces which re-launched Croft Original in the style mags, I wrote a really rude letter back. I could kick myself now. Imagine all that free sherry.

I don’t believe that advertising is evil. It helps keep a free press going, including this magazine. I don’t subscribe to the late, great Bill Hicks routine: ‘By the way, if anyone here is in advertising or marketing: kill yourself. Seriously though, if you are, do. There’s no rationalisation for what you do and you are Satan’s little helpers. You are the ruiner of all things good. You are Satan’s spawn filling the world with bile and garbage.’

They lure people in to spend money they haven’t got on pointless stuff for people they don’t like

I do believe, however, that the advertising industry needs to stop kidding itself that it is in any way helping civilisation. We’re now so concerned with fake news and social media conspiracies that the industry has been let off the hook in recent years. Make no mistake, though. These agencies wouldn’t know a principle if it stuck itself right up their noses.

As we approach Christmas, the syrupy cynicism becomes especially irritating. John Lewis (and adam&eveDDB, which makes its adverts) are the worst offenders. Their first stab at a full-blown narrative Advent advert in 2011 (fidgeting child counts down the days while a Smiths song is defiled in the background) was hugely successful, although it didn’t actually appear to be advertising anything at all. The only goal was ‘branding’. It was designed to make us associate John Lewis itself with the sort of warm, fuzzy, nostalgic feelings that we’d normally only associate with Christmas. This year’s John Lewis advert — which features a young black boy introducing an alien white woman to her first Christmas — seems to suggest that the only good white person is one from another planet.

And why do John Lewis adverts always have such miserable music? I was taken aback when ‘edgy’ Lily Allen droned that soppy Keane song for the Lewis lucre in 2013. At least she had some shame. Five years later, she claimed her record label had ‘bullied’ and ‘betrayed’ her into doing the ad.

Before long, every big company was tugging at our heartstrings. I recall with especial distaste the year that Sainsbury’s attempted to co-opt not only our Christmases but our armed forces. The clip in which a returning soldier surprises his family while they’re in the middle of recording him a Christmas video message was genuinely moving, but that only made the fact that it was being used to flog cocktail sausages all the more offensive. And what about those army families whose loved ones wouldn’t be coming home that Christmas — or any other? Was any thought given to how something like this might make them feel? Of course not. There was money to be made from brave men making the world safe for soft-handed and overpaid brand managers.

Another advertising trick is to present a vision of national unity. Marks & Spencer is guilty of this. Despite its massive losses over the past few years, it appears to think it is bringing the country together with its over-priced Yuletide tat. This is not just cynical Christmas grifting gimmickry — this is M&S cynical Christmas grifting gimmickry.

But all Christmas adverts are the same to some degree. They knowingly lure a lot of people in to spend money they haven’t got on pointless stuff for people they don’t like, thereby establishing that credit-card companies and divorce lawyers will be among the few people waking up perky on 1 January.

We are herded into the commercial Christmas corral like gormless reindeer. As a Christian myself, albeit a bad one, I really do feel that one of my special times of the year has been totally culturally appropriated by greedy non-believers. Let Christmas be Christmas. Now that’s an advertising slogan.

Why the next election will be harder for the Tories

Ever since Boris Johnson’s disastrous decision to try to stay the standards committee’s guilty verdict against Owen Paterson, things have started going wrong for Downing Street. The roots of the government’s problem can be traced back to a speech, though. Not Johnson’s rambling address to the CBI earlier this week, but his speech at Tory party conference last month.

Johnson wrote much of the speech on various plane flights. David Cameron’s conference speeches, in contrast, were normally the result of long, painful writing sessions for him and his aides. Yet one advantage of writing the Prime Minister’s speeches by committee was that it forced everyone involved to think through what the government’s priorities were, what it was actually trying to achieve.

Johnson’s conference speech was the ultimate Boris Johnson address: good jokes, but not much policy. It went down a storm in the hall and few politicians could have pulled it off. But it didn’t actually clarify the government’s priorities.