-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Emma Raducanu’s victory is being spoiled by the usual suspects

How do you take the pleasure out of something so marvellous and joyful as Emma Raducanu’s US open victory last night? Easy — turn on Twitter, which spoils everything including sport.

Raducanu’s victory is truly a great triumph; the most breathtaking sporting feat by a female British athlete in our lifetimes. Emma is 18 and beautiful, just did her A-levels and got A* marks, had been 400/1 to win the tournament, never dropped a set — all these facts make her achievement even more delightful. I’ll stop the adulation there, because an entire industry of sports commentators already exists to make these points over and over. We don’t all need to join in. Yet for some reason it’s expected that we do.

Remember the Euros — it was only two months ago — when every Twitter blue-tick decided his or her online status demanded endless pronouncements on England and other matches? It’s the same deal. Politicians started posing online as serious tactical analysts. Lifeless corporate accounts lectured us about passion, the Three Lions and racism. People who don’t usually follow sport at all pretended to be fanatical about it.

Idiocy is memetic and social media has created that most awful of creatures: the blue-check omnipundit, who has to have their say about absolutely everything. Some sports people pronounce incessantly about politics, too, you may have noticed.

Even weirder is the habit of clueless media addicts to issue formal statesman-like congratulatory tweets to victors, or commiseration to the losers, as if they were some dignitary presiding over the closing ceremony.

The retweet-junkies of the world know that major sporting events are great opportunities to generate online engagement and improve your profile. The more vapid the better. (Confessing to being ‘too tense to watch’ while still endlessly tweeting is a good one).

The worst part is that, because even on social media everybody gets tired of making the same point, the political-cum-culture wars come crashing in.

That’s why Alastair Campbell, who should probably be having a break from the internet after his performance on Wednesday, felt compelled to tweet-lecture Priti Patel, the Home Secretary whose family come from Uganda and India, on what Emma’s story teaches us about the blessings of immigration. Other Labour figures did the same.

Idiocy is memetic, did I say that already?

There’s already been a mental health row over Emma. Piers Morgan was vilified for suggesting ‘she couldn’t handle the pressure’ after she withdrew from Wimbledon suffering from anxiety on court. Morgan is now being attacked for ‘backpedalling’ because he too has now applauded her victory.

No doubt a sexism row will now follow — about whether it’s creepy or patronising for men to thrill at female tennis stars. You can’t like Emma if you are a cis white male. Online, the fun is often all about ruining other people’s enjoyment.

On a brighter note, Jamie Carragher the retired footballer tweeted something genuinely funny about Larry David in the crowd at the Arthur Ashe stadium. And Raducanu’s own social media profile is endearingly amiable, restrained and professional. If only the political class and the rest of us could do the same.

China’s war on effeminate men

A rectification notice from China’s state censor earlier this month included a peculiar admonition to ‘resolutely oppose’ effeminate men on television. The note stood out in the otherwise dry document. Its other targets — people with ‘poor morals’ or ‘lacking solidarity with the party and nation’ — make sense within Beijing’s authoritarian logic. But it’s hard to conceive of pretty boys in eyeliner joining the party’s long lists of revolutionary enemies.

The term used for effeminate men in the notice — niangpao — is vague, but the National Radio and Television Administration is counting on its broadcast partners to know what it means. An example of the sort of effeminate men Beijing feels threatened by is hard to locate in Western pop culture. The problem for regulators is not sexuality. The Chinese state is not always friendly to its gay and transgender communities but the uneasy sexual relaxations of the last decade do not seem in any danger of being undone. The problem for censors is that, like grumpy old people shouting at their TV screens, men just don’t look like men anymore.

Figures within the Chinese leadership can see what’s on the horizon

One of the first signs of a potential assault on effeminate men came when English-language news reported on a social media post titled, ‘Do you know how hard the CIA is working to get you to love effeminate stars?’. The short essay was published by an account called Torch of Thought, which is linked to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The article introduced the figure of Johnny Kitagawa, a Japanese-American impresario who was plugged into the American occupation’s efforts to rebuild pop culture in vanquished Japan. Torch of Thought paints this now-dead talent manager as a paedophile Svengali determined to end warlike masculinity and turn Japanese men into kittens.

When Japan’s economy imploded in the 1990s, South Korea took up where they had left off. South Korea left Japan far behind in the androgyny arms race. When androgynous Korean boyband Super Junior broke into China in the early 2000s, the trend was established. The niangpao were here to stay. But now the National Radio and Television Administration wants them gone.

The decision by a Chinese censor to address the issue may seem uniquely bizarre, but it comes after both Japan and Korea went through their own debates about masculinity in crisis. In those countries, the counterweight to androgynous idols had been the strong, silent salaryman. He put on a tie every morning, as solid and reliable as the firm where he worked. Even if his daughter liked boys with floofy hair, she was going to marry a man like her daddy, get pregnant, quit her job, and pop out the demographically required number of children.

But as both countries did away with the idea of employment for life, cajoled women into the workforce and made dual incomes a necessity, the lone male breadwinner was no longer a workable notion. The result of all this has been cratering birth rates, an epidemic of men reaching middle-age without losing their virginities and a society trapped in an enervating permanent adolescence.

Figures within the Chinese leadership can see what’s on the horizon. At this point, there have been a few levers pulled beyond the liberalisation of family planning rules. It seems there is little stomach for changing the economic game which underlies the demographic crisis.

The main fix for fertility, although certainly not an easy one, would be to aggressively cool off the real estate market. Rearing a family is predicated on being able to afford one. As overseas financial markets have been restricted, the flats and duplexes of China’s booming cities have transformed into assets. Beijing recognises the problem. Shortly after taking office, Xi Jinping issued an admonition: ‘Housing is for living in and not for speculation’. Recognition is one thing, fixing the problem is quite another.

Cultural levers are easier and cheaper to pull. The one-child policy is long gone. But reforming the economic structures that have enriched party allies is far less attractive. Instead, the CCP has put out a tersely worded notice resolutely opposing effeminate men. Without concrete support to boost the fertility rate, they hope that people can be convinced to have children by promoting a more well-groomed, Norman Rockwell-esque vision of masculinity and family. Xi Jinping’s ‘China dream’ looks awfully like the American one he hopes to overthrow.

Was the US involved in neo-fascist Italian terrorism?

Last month, Italy’s Prime Minister Mario Draghi promised to declassify government documents involving two organisations: Gladio, an anti-communist paramilitary group linked to Nato and the CIA, and a masonic lodge known as P2. These two groups are believed by some to have been involved in the darkest moments of post-war Italian history.

For much of the latter half of the 20th century, Italy had the unenviable position of being the epicentre of European terrorism. The blast at the Bologna train station in 1980, which left 76 people dead and more than 200 wounded, was at the time the bloodiest terrorist attack ever suffered by a European country. The bombing was pinned on a small neo-fascist militia called Armed Revolutionary Nucleus. But many Italians remain convinced that the attack emerged from a wider far-right network. Draghi’s decision to declassify the papers came on the 41st anniversary of the Bologna killings.

Post-war Italian psychology was shaped by the overwhelming forces of the USSR stationed just a couple of hours drive from the north eastern border

Post-war fascism in Italy was predicated on a ‘strategy of tension’. The term, coined by British journalist Neal Ascherson in the Observer in 1972, describes all sorts of plots, including assassinations and false flag terrorist acts, carried out with the aim — not of destabilising the country — but of consolidating power and justifying emergency laws. When I asked Senator Felice Casson, the prosecutor who headed the investigation into Gladio, what his opinion was of Draghi’s decision, he replied ‘Fuffa!’ — ‘just crap’. Casson explained: ‘It’s just an announcement. There is not the courage nor the will to disclose the involvement of foreign powers.’ In 2001, Guido Salvini, a judge involved in the Massacres Commission, claimed: ‘The role of the Americans was ambiguous, halfway between knowing and not preventing and actually inducing people to commit atrocities.’

The truth of such claims — denied by the US State Department — remain unverified. Perhaps Draghi’s new documents will point to greater American involvement. Certainly in the immediate aftermath of world war two, the US took exceptional interest in Italy’s politics. The CIA has admitted giving the equivalent of over $11 million to centrist parties at the 1948 election, while there is evidence that the Americans faked letters in order to incriminate left-wing candidates. Italy was a special case among Nato countries. For one thing, it had the largest and most powerful communists party outside the Eastern Bloc, the Partito Comunista Italiano. This was intolerable to the Americans for whom Italy was strategically too important to lose.

Italian psychology at the time was shaped by the overwhelming forces of the USSR stationed just a couple of hours drive from the north eastern border. Part of the plan for an armed resistance against a Soviet invasion was Gladio, a kind of Dad’s Army of willing anti-Soviets. These so-called ‘stay behind’ units were trained in guerilla warfare and existed throughout much of Europe. In 1991, it was revealed that Swiss Gladio members had been given combat training by the British army without the Swiss government’s knowledge or approval. Some of Gladio’s Italian members were indeed members of far-right terror groups, according to the Massacres Commission judge Guido Salvini. As in post-war Germany, where former Nazis were recruited by the Americans to fight in the Cold War, the post-war Italian government also signed up former fascists, who were the most ideologically motivated to fight communism.

This explains the role of the masonic P2 lodge, short for Propaganda 2 (Propaganda 1 was founded in 1877 and shut down by the Mussolini regime). P2 was a secret freemason organisation consisting of prominent politicians, businessmen, members of the secret service, the armed forces and influential journalists. P2’s goal was to infiltrate the state and make it impossible for the communist party to take power by democratic means. Its existence became public in 1980 and was then declared illegal shortly after in 1982. The lodge has been linked to the failed coup of the Roman prince Junio Valerio Borghese and the bombing of the Italicus train of 1974.

By the 1980s numerous corruption scandals began to surface. First came an investigation into P2 and its members, then in 1990 the existence of Gladio was formally recognised. The investigation into Gladio — first exposed at the 1984 trial of a neo-fascist terrorist — provoked outrage, but its existence proved to be of little real consequences. The Berlin Wall was crumbling and the scandal provided a useful smokescreen for the crimes perpetrated by high ranking members of the communist party. They were fearful that revelations could spill out from the disintegrating Soviet archives, revealing how the Italian communist party had been illegally sponsored by the USSR up until the late 1980s. To be subsidised by your enemy, a power hostile to the alliance to which Italy belonged, with nuclear rockets pointed at your territory, constituted a much higher treason than belonging to Nato’s secret Gladio organisation.

Evocations of the fascist peril have become an

effective tool in post-war Italian politics to silence adversaries. As much as he might want to get to the truth of Italy’s strange history of neo-fascism and international intrigue, there are domestic reasons for Mario Draghi’s initiative: an attempt to keep the Fratelli d’Italia at bay. Fratelli, according to some polls now the most popular party in Italy, is the successor of post-war Mussolinist tendencies. Now, however, Fratelli is attempting to present itself as a normal conservative party. Nailing it to its past, to its post-fascist roots, is good politics for Draghi.

Rosie Duffield’s treatment brings shame on the Labour party

News that Rosie Duffield will be missing the Labour Party conference over threats to her personal security brings to a head an appalling situation where a female Labour MP cannot stand up for the rights of women without triggering opprobrium. Keir Starmer cannot and must not sit on the fence any longer. Maybe he is trying to sit tight and hope that this goes away? This seems unlikely: Duffield’s opponents are motivated by an evangelistic zeal to silence those who dare to disagree with them.

Thankfully, Duffield isn’t taking the hint On Friday, she spoke more sense into the debate:

Duffield might be the lightning rod, but the problem is much wider

No doubt there will be yet more calls for the whip to be withdrawn from her. The bullying and harassment of Duffield has been ongoing since she expressed her view that ‘only women have a cervix’, and it has become a stain on the party. Let’s be clear, Duffield is neither homophobic nor transphobic; she just doesn’t believe that men can become women by signing a piece of paper.

As a trans person myself, I agree with her: men cannot become women under any circumstances, whatever the LGBTQIA+ lobby might have us all believe. Women are female, men are male, and sex in humans is immutable. Duffield is also correct to be concerned about the right of women to protect single-sex spaces based on biology. Make-believe is no substitute for reality.

Karl Marx knew that. He rejected the idealism of fellow German philosopher Georg Hegel; he also said, ‘social progress can be measured by the social position of the female sex.’ But shockingly, it seems that in today’s Labour party, the female sex cannot protest this new idealism.

Four thousand miles away in Kabul, women are being forced to stay home by a misogynist regime that has seized power in Afghanistan. No doubt this situation will be protested vociferously at the Labour party conference. But it will ring hollow if one of their own MPs – a woman whose harrowing account of domestic abuse shocked the House of Commons – finds herself staying home during the party conference.

Starmer has a little over two weeks to sort out this mess. The party claims that its Brighton shindig will be ‘a real opportunity to be a part of democracy in action.’ That will be open to interpretation if they cannot guarantee the safety of women accused of wrongthink by the transgender lobby.

Duffield might be the lightning rod, but the problem is much wider. The party has drifted far from the electorate they once took for granted. While self-identification of legal sex might excite young political activists within the party, the voters on the red wall have other concerns, not least jobs, health, education and public services. They also know the difference between men and women.

The people going after Duffield are certainly devoted to their own opinions, creeds and dogmas. Starmer needs to find his backbone and stand up to them before they consign the Labour party to the political wilderness for years to come.

Rosie Duffield to miss Labour conference due to security concerns

Labour conferences have been fractious affairs in recent years. Tensions between various factions have often spilled over onto the conference floor, with the Corbyn era being particularly notable for the divides between Labour’s membership and parliamentary party. A particular low point was Luciana Berger being required to have a police bodyguard at the 2018 conference after threats were made against her.

New leader Keir Starmer is keen to show such acrimony is a thing of the past. This year’s Brighton jamboree is set to begin in a fortnight’s time and is being billed as the Labour leader’s first big in-person test to an audience of the faithful. Elected in April 2020, Starmer will be hoping his initial year and a half leading his party will be enough to ensure a standing ovation.

One person who won’t be in that audience however is the MP for Canterbury Rosie Duffield. A poster girl for Labour’s surprise successes in the 2017 election, Duffield has attracted both praise and opprobrium for her views on transgender issues. Back in August last year, LGBT+ Labour demanded Starmer ‘take action’ against Duffield after she wrote on Twitter that ‘only women have a cervix.’

More rows have followed since, with a member of Duffield’s staff resigning over what they called her ‘openly transphobic’ views and LGBT+ Labour criticising her Twitter activity. For her part, Duffield has insisted that she continues to support to trans rights and believes that ‘people have the right to live with dignity and be treated with respect in an equal and inclusive society.’

But Steerpike understands that Duffield will be missing her own party’s conference over concerns about the threat to her personal security. It comes just a day after the MP complained on Twitter about the ‘mostly male aggression and verbal abuse’ which ‘has resulted in changes to my personal safety and security arrangements.’

Let’s hope Starmer is able to ensure his own MPs are safe at next year’s party conference.

You can’t keep an American exceptionalist down

Like millions of other Americans I was riveted by the images of chaos and despair at the Kabul airport as US forces finally left Afghanistan, yet another sad result of a forever foreign policy driven by ignorance, overreach and hubris. But as distressed as I was by the sight of desperate Afghans clinging to the exterior of a moving US Air Force cargo jet, what truly horrified me was the flood of belligerent anti-withdrawal nonsense uttered in print and on TV by an American political and media establishment that has apparently learned nothing since the Korean War, when General Douglas MacArthur provoked China’s invasion of North Korea by pushing too close to the Chinese border.

On and on, network news, cable talk shows and the editorial and op-ed pages of major newspapers trotted out the discredited villains and useful idiots – all of them fluent in Cold War dogma, humanitarian intervention and the ‘War on Terror’ — who in recent years have done so much harm in the world and contributed to the deaths of so many innocent people.

The good news is that Biden didn’t bend this time to America’s neo-imperialist impulse. The bad news is that he’s vastly outnumbered.

We were, it is true, spared the bombast of former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, who mercifully passed away before the Taliban returned to power. We did, however, hear repeatedly from his doppelganger, Paul Wolfowitz, intellectual architect of the 2003 Iraq invasion, in the Wall Street Journal. Wolfowitz had wisely kept a low profile since the glorious reformation of Iraq turned sour and had left government, but you can’t keep an American exceptionalist down, especially not one as profoundly vain as the former deputy secretary of defence.

The day after suicide bombers killed 13 US soldiers and at least 170 civilians in Kabul, Wolfowitz was hard at work trying to rejuvenate the ‘Forever War’ against terrorists, who like communists, it seems, just love to congregate in America-hating countries: ‘The war with that gang and its affiliates won’t end because the U.S. has quit…It’s a shame they [ISIS-K and the Taliban] can’t both lose…but whoever wins will make Afghanistan a haven for anti-American terrorists.’ That’s why we were in Afghanistan for twenty years and spent more than two trillion dollars, ‘…to prevent a murderous gang from regaining control of Afghanistan, where they….enabled an attack that killed nearly 3,000 people on American soil.’ This from a man who encouraged the belief that the anti-Islamist Saddam Hussein was in league with the Saudi Islamist Osama bin Laden, and that Iraq possessed atomic bombs and a big arsenal of chemical weapons. Wolfowitz also appears unaware that no Afghan tutored the 9/11 hijackers in avionics, and that no member of the Taliban enrolled in the Florida flight school that taught two Arabs how to pilot the commercial jets that hit the World Trade Center.

But the neo-conservative fanatic of yesteryear was only one in a parade of critics from all across the political spectrum. On liberal National Public Radio came steady lamentations over the abandonment of Afghan women, who had been encouraged by the American occupiers to develop big ideas about their social status, and even to become jet airplane pilots. Wolfowitz expressed solidarity, employing a metaphor that might have been lifted from the movie Being There: ‘Like a gardener who pulls up weeds to allow plants to grow, keeping the Taliban off the backs of the Afghan people would have enabled them to continue some of their impressive successes, particularly in educating girls and women…’

We all agree that Afghan women should be given a fair shake. But did anyone seriously think that prolonging the US occupation would do anything other than prop up the Potemkin village known as the Afghan government and provoke more violence by the Taliban and recruitment to their cause? Yes, many serious people thought just that, like the normally thoughtful columnist Bret Stephens, who in the New York Times posited, ‘I thought we could have maintained a small and secure garrison that would have provided the Afghans with the air power, surveillance and logistics they needed to keep the Taliban from sweeping the country.’

In contrast to the Journal, the Times was more sympathetic to President Biden, though most days I couldn’t see the difference. A long op-ed by former ambassador Ryan Crocker decried the Administration’s ‘lack of strategic patience’ and claimed that withdrawal ‘has damaged our alliances, emboldened our adversaries and increased risk to our own security.’ Times columnist Maureen Dowd, a liberal, supported Biden’s decision, but not before she bemoaned our ‘catastrophic exit.’ If it was catastrophic, then why was it a good idea to leave? I suppose that as a member of the Washington consensus she was doing her best to keep in step with the former commander of allied forces in Afghanistan, David Petraeus, who in the Journal called the withdrawal ‘disastrous.’ Other media and political personalities were not to be outdone: ‘Shameful’ (The Week); ‘Imbecilic’ (Tony Blair); ‘Biden’s Teheran’ and ‘Dumkirk’ (New York Post).

I’m not arguing that all critics of the Afghanistan departure are necessarily fools. But the hysterical reaction to Biden’s common-sense decision to cut American losses demands more reflection and analysis. For me it recalled not so much the fall of Saigon in 1975, to which it is often compared, but rather the fall of Khartoum in 1883 and the death of General Charles Gordon. Substitute the Mahdi — the religiously inspired leader of the Sudanese rebellion against Egyptian and British control – for the Taliban and we have an equivalent casus belli, with Western civilisation itself besieged by the savage Islamic fundamentalism described in Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians: ‘The faithful…were to return to the ascetic simplicity of ancient times’ in which criminal conduct was punishable by ‘executions, mutilations, and floggings with a barbaric zeal. The blasphemer was to be instantly hanged, the adulterer was to be scourged with whips of rhinoceros hide, the thief was to have his right hand and left foot hacked off in the market place.’ To the rescue, amidst ‘a blaze’ of popular and press excitement in England, was sent the half-mad GeneralGordon, whose own moralistic, ascetic and religious vanity exceeded even that of General MacArthur. Gordon was a liberal reformer in some respects, but he was mainly a narrow-minded adventurer of almost insane ambition – ‘ambition, neither for wealth nor titles, but for fame and influence, for the swaying of multitudes,’ as Strachey writes. The description fits Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz and Petraeus to a T, but it also resembles the multitude of liberal interventionists who populate the US foreign affairs and media elite. Americans flatter themselves that they are not imperialists, as were so many British Victorians, and that they promote liberal values, not conquest, profit and cultural domination.

But they’re not as different from the Victorians as they believe, and their allegedly virtuous ambition remains world-straddling, in keeping with the more than 700 US military bases scattered around the globe. The good news is that Biden didn’t bend this time to America’s neo-imperialist impulse. The bad news is that he’s vastly outnumbered.

The War on Terror is a war of religion

Compare the world 20 years after the 9/11 attacks to the world two decades after Pearl Harbour. World War Two was a vivid presence in popular culture and national memory in 1961, but America in the first year of John F. Kennedy’s administration was in no sense living in the shadow of Japan’s attack. That war had ended 15 years ago; Japan was now our ally in the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

Twenty years after 9/11, the US has only just ended its war in Afghanistan, and the result of that conflict, which lasted five times longer than the one with Imperial Japan (and Hitler’s Germany), was the immediate return to power of the regime we set out to depose at the start.

After Afghanistan, the US is still fighting a War on Terror against al-Qaeda and similar groups. The foreign-policy community continues to dream of bringing regime change to the Islamic world, while weapons of mass destruction at the disposal of the ‘Axis of Evil’ remains a preoccupation of our diplomats and think-tankers, or tank-thinkers.

Like a classic war of religion, its objective is the claiming of territory for the faith and ultimately the conversion of the people who live there

This is what ‘forever war’ means. And in fact, it began at least a decade before 9/11, with the 1991 Persian Gulf War that didn’t really conclude successfully and cleanly but instead became an open-ended policing operation over the skies of Iraq and in the purported deports and workshops of Saddam Hussein’s WMDs. Congress was still fighting the Gulf War in 1998 when it passed the ‘Iraq Liberation Act’, five years before George W. Bush invaded in full force.

1998 was also the year Bill Clinton’s administration launched air strikes against al-Qaeda camps in Afghanistan (and Sudan) in retaliation for the group’s attacks on US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania earlier that year. Terrorists with al-Qaeda connections had previously bombed the World Trade Centers in 1993, and al-Qaeda would strike the USS Cole in 2000. The 9/11 attacks were not the start of something, a moment in which ‘everything changed’, but an intensification. So was the US response.

Iraq and Afghanistan were already theaters of conflict, though they would become much bloodier in the 2000s. Everything the US had done up to 9/11 — the Gulf War, the airstrikes, economic and diplomatic sanctions — failed to curtail the problem. The invasion of Afghanistan after 9/11 did seriously degrade al-Qaeda, and bin Laden himself eventually met a deservedly violent end. But surprisingly little else is resolved. Iraq is no longer much covered by the US media, yet its fate remains precarious. In 10 years’ time, Afghanistan might not be the only place where the post-American order looks appalling like what came before.

To say that the War on Terror is unwinnable because it’s a war on an abstraction is true enough. In practice, however, the War on Terror is simply a name that’s been slapped on America’s post-Cold War engagement with hotspots in the Islamic world. That isn’t a war on an abstraction, but it is a war of a curious character. It’s not like war with Japan or the Cold War with the Soviet Union. So what sort of conflict is it?

It’s a war of religion. And like a classic war of religion, its objective is the claiming of territory for the faith and ultimately the conversion of the people who live there. This is what it means to bring liberalism and democracy to Iraq or Afghanistan, or indeed to the Islamic world as a whole. The 1991 Gulf War had more limited objectives, of course, but those objectives proved to be self-unlimiting. We rescued Kuwait — and maybe by proxy Saudi Arabia — but this left a lingering question of what to do about Iraq. The only answer, according to the secular religion of America’s leadership class, was conversion. Iraq must become liberal and democratic one way or another — by sanctions, by threats, by invasion, by occupation. This would redeem Iraq, and Iraq would redeem its neighbors, above all Iran.

The reality, of course, is that Shi’ite militias wield much of the power in democratic Iraq, and Iran exerts a considerable influence on its neighbor, not the other way around. In Afghanistan, where the American work of proselytizing was ongoing for 20 years, the old heathenism was never stamped out and speedily reasserted command once the armed missionaries left.

Groups like al-Qaeda make explicit claims to be waging religious war or jihad. Most Muslims reject them. That rejection is not, however, the same thing as embracing the secular religion we have tried to export. Yet because our goals are indeed religious, not merely pragmatic, all the military skill and financial resources we bring to bear on countries like Afghanistan and Iraq fail to achieve our ultimate aims. Overthrowing a dictator is easy — redeeming a people is not only hard, it’s unintelligible in strategic terms.

The Taliban’s success might suggest otherwise, but the Taliban’s goal is not redemption, it’s submission. And the Taliban are a native force, with roots in the land as well as in faith. The paradoxical aim of Western elites when they make plans for the Islamic world is to build not a humble, functional, imperfect earthly order, but the City of God — only without God. This is so far from being feasible that the time and resources required to achieve it cannot be anything less than infinite.

Terrorists like bin Laden have often sought to justify their crimes by claiming to act in defense of their faith. Bin Laden was even known to claim that al-Qaeda’s existence was partly inspired by the sacrilegious presence of US troops in the holy land of Arabia. The mundane truth is that bin Laden wanted power, and anti-Americanism was a path to that. A garden-variety dictator like Saddam Hussein had power in one sense, but bin Laden wanted something different and potentially greater — al-Qaeda was internationalist in orientation from the beginning. Its founder wanted to be a revolutionary. His religion was entwined with that.

Perhaps ironically, Western policymakers are the opposite: they think of themselves as revolutionaries, when they are more like theologians. They believe that their faith is the end of history itself, and if only a strange people can be introduced to it, they will invariably adopt it. How can they fail to, when its truth is so obvious? Western leaders were not always like this, but the end of the Cold War taught a new generation of leaders — baby boomers like Bill Clinton and George W. Bush — all the wrong lessons.

The wars John F. Kennedy fought, the Pacific War in which he served and the Cold War he waged as president, had attainable ends, however idealistically they might be portrayed in propaganda. The wars of the post-Cold War era have drifted toward unattainable visions, whose academic and technocratic articulation only serves to distract from their basically eschatological character. So these wars are never won — not 30 years after the Gulf War and 20 years after 9/11.

The very American heroism of Todd Beamer

Twenty years ago today, on the morning of 11 September 2001, 32-year-old Todd Beamer boarded a United Airlines flight at Newark, New Jersey, bound for a business meeting in San Francisco. He was due to fly back that night, to rejoin his pregnant wife, Lisa, and their two young sons, Drew and David. Todd worked for a computer company, selling software. His job entailed lots of travelling. This was just another working day.

Forty-six minutes after take-off, terrorists stormed the cockpit, seized the controls, and announced, ‘We have a bomb onboard.’ The plane changed course for Washington DC. Some passengers managed to make phone calls to friends and family, and news soon spread around the cabin that two planes had crashed into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York – and that a third plane had crashed into the Pentagon. It quickly became clear to Todd, and everyone else onboard, that theirs was the fourth plane.

Todd Beamer tried to make a credit card call and ended up talking to a call center supervisor for the firm who handled United Airlines’ in-flight phone service. The supervisor’s name was Lisa Jefferson (Todd was struck by the strange coincidence that she shared his wife’s name). Their 13-minute conversation is a precious record of an extraordinary act of heroism, a testament to the bravery and humanity that survived that awful day.

Even faced with almost certain death, American democracy prevailed

Todd and Lisa recited the Lord’s Prayer together. They recited Psalm 23 (‘Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil’). Other passengers joined in. Todd remained remarkably calm, though his voice rose a little when the plane went into a dive. ‘Lisa, Lisa!’ he cried out. ‘I’m still here, Todd,’ replied Lisa. ‘I’ll be here as long as you are.’

Todd and a group of fellow passengers (and several flight attendants) held a council of war, and took a vote, and resolved to storm the cockpit (even faced with almost certain death, American democracy prevailed). ‘If I don’t make it, please call my family and let them know how much I love them,’ he told Lisa. The last thing she heard him say was, ‘Are you ready? OK, let’s roll.’

Todd and his fellow passengers must have known their chances of success were miniscule, but they preferred doing something to doing nothing. They preferred to go down fighting. Thanks to them, Flight UA93 never reached Washington, and its intended target: either the White House or the US Capitol (though Vice President Dick Cheney had given orders that the plane should be shot down). It crashed in an empty field in Pennsylvania. Everyone onboard was killed. Four months later, on 9 January 2002, Todd’s widow, Lisa Brosious, gave birth to a healthy baby girl.

Todd Beamer was born in Flint, Michigan, in 1968. He had an elder sister and a younger sister. His dad was a sales rep for IBM. He was raised to respect hard work and the Bible. He attended Wheaton Academy, a Christian high school, and Wheaton College, a liberal arts college. A talented sportsman, his hopes of playing professional baseball were curtailed by a car accident. He met Lisa Brosious at Wheaton in 1991. They married in 1994. They taught Sunday School together. Todd played for his church softball team.

The day before 9/11, Todd and his wife Lisa had just returned from a trip to Italy, awarded to him by his company to reward his prowess as a salesman. Todd could have flown straight on to San Francisco, but he wanted to spend the evening with his young family. After Todd’s death his good friend Doug Macmillan gave up his job to run the Todd Beamer Foundation, which supports children whose parents perished on Flight UA93.

Why is Todd’s story so important? And why should we remember it today? Well, for the same reason we remember any heroic deed, to ensure that those who gave their lives to save others aren’t forgotten. However, in this instance, there’s more to it than that. ‘Let’s roll,’ became a clarion call, a cri de coeur, a declaration that America was undefeated, that its values endured. Good and evil are unfashionable terms in modern news reporting, but it’s hard to conceive of a darker deed than mass murder, and it’s hard to conceive of a greater deed than trying to prevent mass murder taking place.

If Todd Beamer had survived, where would he be today? Maybe he’d have a desk job by now – no more red-eye flights to San Francisco. Maybe he’d be the coach of his church softball team. Whatever he was up to, I reckon he’d still be doing the right thing. That’s the thing about heroism – it takes a lot of practice. You need to stay in shape.

If Todd hadn’t been on that flight, we probably never would have heard of him, but I bet he’d have spent the last 20 years performing countless little acts of kindness, enriching countless lives. If you’re lucky, you’ll never have to do that one big thing that everyone remembers. But you need to do the little things – it’s the little things that get you ready. Todd Beamer was unlucky, but when the big moment came, he was prepared for it. ‘Are you ready? OK, let’s roll.’

Does Nicola Sturgeon care more about oil revenue or climate change?

‘Now, as I’ve hopefully made clear throughout all of my remarks, the North Sea will continue to produce oil for decades to come. It still contains up to 20 billion barrels of recoverable reserves. Our primary aim – and I want to underline and emphasis this – our primary aim is to maximise economic recovery of those reserves.’

The words are from a speech made in June 2017, a few months after the Paris Agreement that aimed to limit climate change came into effect. A speech by a pro-oil Conservative, or perhaps the head of an industry group working on behalf of the oil sector? No. They are, in fact, the words of First Minister Nicola Sturgeon speaking at the Oil and Gas UK Conference that year.

Skip forward to a few weeks ago and we find a far less confident First Minister struggling to respond to climate activists who challenged her to ‘oppose Cambo’, a reference to the Cambo oilfield development off Shetland. A decision on whether Cambo, which was granted an exploration licence in 2001, becomes a commercial field (it is thought to contain 800 million barrels of oil) currently sits with UK regulators and is proving controversial in light of the climate challenge.

Having recently brought two Scottish Green party ministers into her government, with the COP26 climate conference taking place in Glasgow later this year – and with yet another economic prospectus for independence said to be in the works – Sturgeon’s position on oil and gas extraction will increasingly be in the spotlight. That begs the question as to how important oil and gas is to the independence movement today: is it an asset or a liability?

If Scotland had broken away it would have been the biggest mis-selling scandal in history

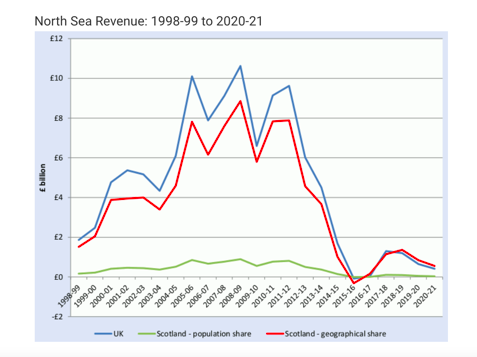

In one sense, the economic assessment has become much simpler. Oil and gas tax revenues are a fraction of what they once were. The latest official Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland (Gers) numbers, which monitor Scotland’s share of offshore revenues on both a population split and geographic split basis, shows this clearly (see graph below). The days of multi-billion-pound annual oil tax revenues pouring into government coffers are over.

The Salmond-Sturgeon 2014 independence prospectus was sold on the basis that Scotland’s structural fiscal deficit would be mitigated by ongoing multi-billion-pound annual tax receipts from the North Sea. The reality is that in 2016, the year Scotland would have seceded following a ‘Yes’ vote, Scotland’s geographical share of oil revenues went negative for the first time. If Scotland had broken away it would have been the biggest mis-selling scandal in history.

The danger of relying on North Sea revenues as a key pillar of the economic case for separation was recognised in 2018 when the SNP updated its independence pitch. The party’s Sustainable Growth Commission report recommended oil revenues be seen as a ‘windfall fiscal bonus’ and not relied upon for fiscal management.

In disregarding oil revenues, therefore, Sturgeon is on safe ground – indeed, the more interesting and contentious discussion is on how much tax relief-based costs associated with decommissioning a future independent Scotland would take on as part of the divorce settlement. That means Sturgeon’s reluctance to come out against further oil and gas extraction is likely more to do with jobs and unease at being seen as the enemy of an industry she spent years defending.

The oil and gas sector contributed £16.2 billion in gross value added to Scottish GDP in 2019 (around ten per cent of Scotland’s GDP), supporting an estimated 105,000 jobs. That’s a big chunk of economic activity and a lot of voters to potentially disgruntle.

Thatcher’s radicalism for rapidly dismantling declining industries might be shared by the Scottish Greens, but Sturgeon’s instincts are far more conservative.

After being confronted by the Cambo protestors, Sturgeon, in a feeble attempt to neutralise the fallout and re-bolster her green credentials without actually changing her position, wrote a letter to Boris Johnson. She asked for Cambo and other licences to be ‘reassessed in light of the severity of the climate emergency we now face, and against a robust Compatibility Checkpoint that is fully aligned with our climate change targets and obligations’.

Job done. Let’s get back to spuriously presenting Scotland as leading the world on climate change on the basis of emissions targets that any legislature anywhere could make and that, as with hospital waiting time targets, can easily be broken at no cost.

Sturgeon’s positioning on oil and gas extraction is to sit on fence as long as possible. Whether the climate lobby or the oil and gas lobby let her is another matter.

The rise of Taliban Twitter

The Taliban takeover of Afghanistan was swift, but this victory wasn’t won overnight. For years, the Taliban has been waging a softer fight: one on social media. Since it was removed from power, the Taliban has dedicated enormous resources to developing its presence online.

As it successfully recaptured Afghanistan, the propaganda opportunities which it put to use on Twitter as the eyes of the world watched suggested these efforts have paid off. Images and videos of Taliban forces easily gaining ground and advancing into Afghanistan’s cities – picking up military hardware left by the Americans along the way – spread like wildfire online. Islamists around the world were delighted.

In the years since it was kicked out of Afghanistan, the Taliban claims to have changed. To an extent this is true, but not in the way you might think.

When it first came to power in 1996, the Taliban banned the internet. Now, it has come to recognise its use

While the Taliban is no less bloodthirsty and ruthless in dealing with its critics and opponents, it now cares more than it did about its appearance in the Western world. When it first came to power in 1996, the Taliban banned the internet. Now it has come to recognise its use and is seeking to use social media to create a positive international image for itself.

Zabiullah Mujahid, the Taliban’s spokesperson, has nearly 400,000 Twitter followers. Suhail Shaheen, another official has almost half-a-million followers, and was this week sharing on Twitter the results of the Taliban cabinet reshuffle. Shaheen has also been eager to show that the Taliban is a serious organisation dedicated to governing Afghanistan properly: one of the first videos he posted in the wake of the American withdrawal was a video of a road being rebuilt. It was a dull clip, but the message was clear: ‘Time to roll up sleeves and build Afghanistan’, he wrote.

Through such posts, the Taliban is trying to use social media to seek legitimacy; its official messages, especially those in English, are moderate, comical even. One recent post showed Taliban fighters enjoying themselves eating ice creams in the baking Afghan heat.

Don’t be mistaken though: for the Taliban’s opponents, this is still an organisation not to be laughed at. A glimpse of this can be seen elsewhere online with images showing what happens to those who fall foul of the Taliban regime not hard to find. Away from Twitter, on encrypted platforms, more fanatical content (and disinformation) is also being shared. Using social media, the Taliban are playing an altogether more unsavoury game, as they seek to radicalise, recruit, and even inspire acts of terrorism.

So what are social media companies doing in response? Facebook has banned Taliban accounts, saying it has ‘a dedicated team of Afghanistan experts’ keeping an eye on content posted on its platform. It has also vowed to take action against Taliban members using WhatsApp (which is owned by Facebook), amid reports the messaging service is being used by the new ruling regime in Kabul.

But Twitter – which is no stranger to taking action against politicians – is adopting a softer approach. Twitter says its ‘top priority is keeping people safe, and we remain vigilant’, yet there is no blanket ban on the Taliban.

At least some Taliban accounts on Twitter are reported to have been set up last year after Sirajuddin Haqqani, the deputy leader of the Taliban, wrote an op-ed in the New York Times. It is believed the aim was for these accounts to promote his article. If so, it appears that the Taliban has learned some key lessons in doing so when it comes to using social media. #kabulregimecrimes was a trending topic on Afghani Twitter in recent weeks, as the old guard fell and the Taliban took over. The Taliban, no doubt, was delighted to see its message circulated so widely online.

So if the Taliban got one over against the United States, it appears to be doing the same to the social media giants of California, who are not doing enough to wise up to the new regime in Kabul. The rise of Taliban Twitter surely demands a rethink of how western tech giants operate. After all, the link between online and offline violence, where people who were recruited or radicalised online carry out attacks, is long established.

Whether Twitter choose to act or not, the damage appears to have been done. For now, as we approach the anniversary of 9/11, the Taliban is on top – not only in Kabul, but also when it comes to winning the fight on social media. When Twitter permanently banned Donald Trump, it said it did so ‘due to the risk of further incitement of violence’. Does that same logic apply to the Taliban?

Covid pingdemic takes its toll on Britain’s economic bounce-back

The arrival of ‘freedom day’ on 19 July enabled people to return to concerts, festivals, and ditch social distancing, but these rediscovered freedoms did not revive the economy. The ONS said this morning that growth was just 0.1 per cent in July, far lower than the consensus forecast. It was particularly disappointing given the growth seen in the locked-down months of June (one per cent) and May (0.6 per cent). The Pingdemic – and concerns about the Delta variant – cancelled out any animal spirits around reopening.

August’s GDP boost is going to need to be much stronger for the more bullish forecasts to pan out

Nightclubs reopened and the entertainment sector was up nine per cent, but the end of stamp duty hit real estate. Capital Economics attributes the stagnation to rising Covid cases and the ongoing pain caused by labour shortages (more on that here). These are factors that are not obviously set to change in the coming months.

If anything, case numbers are likely to worsen in autumn and winter. The raft of measures Boris Johnson is reported to want at his disposal this winter to contain the virus – including a renewal of the emergency powers that would enable the government to reinstate lockdowns – won’t fill businesses with confidence. Meanwhile proposals to require vaccine passports jeopardise the return to normality for many customers and businesses. None of this bodes well for recovery.

August’s GDP boost is going to need to be much stronger for the more bullish forecasts to pan out. There’s some hope here: with the vast majority of the public no longer required to self-isolate after coming into contact with the virus, economic activity may pick up further in the coming months.

But Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s comments today, that ‘our recovery is well underway thanks to the success of the vaccination rollout and the roadmap’, don’t quite fit with the GDP update. Nor do the government’s most recent announcements about tax hikes on both employers and employees inspire much confidence that pro-growth policies around around the corner.

Do vaccines pose a risk to young boys?

Should we be vaccinating children against Covid-19? While some countries have been enthusiastically administering vaccines to under-18s — greatly contributing to their overall vaccination rate — the idea has greeted more coolly in Britain. The government and the NHS were relatively slow in making Covid vaccines available to 16 to 18-year-olds — although it was approved.

Although we are still awaiting a formal government decision on jabbing 12 to 15-year-olds, the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation has recommended that members of this age group only be offered a vaccine if they are especially vulnerable to the virus, citing the risk of myocarditis — an inflammation of the heart muscle — following receipt of the Pfizer vaccine. However, Health Secretary Sajid Javid yesterday said a decision would be coming soon on jabs for these younger teens, while ministers are said to be optimistic jabs will be approved. The AstraZeneca vaccine is already being withheld from under-40s due to the risk of potentially fatal blood clots which have already killed 72 people — and which appear to be more common in younger age groups.

Over a 120-day period, the study found that boys between 12 and 15 had a risk of cardiac issues that was four to six times as high as the risk of being hospitalised with Covid-19

One thing that may swing Javid’s decision is a new US study which attempts to quantify the risk of myocarditis after receipt of an mRNA vaccine (including Pfizer and Moderna). Led by the University of California, it analysed data from the US Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System between 1 January and 18 June this year. It found 257 ‘cardiac adverse reactions’ among double-jabbed under-18s. This risk was found to be much lower for girls than for boys, with 162 cases per million in boys aged 12 to 15 compared with 13 per million for girls of the same age. For older teens, aged 16 to 18, the risk was still high in boys — 90 cases per million — compared with just over 13 per million in girls.

Another worrying factor for scientific advisers making the decision on jabs is the comparative risk of myocarditis against the chance that these younger teens will end up in hospital with Covid. Over a 120-day period, the study found that boys between 12 and 15 had a risk of cardiac issues that was four to six times as high as the risk of being hospitalised with Covid-19. For 16 to 17-year-olds, the risk was two to almost four times as high. The study doesn’t mention any deaths from these cardiac issues and doesn’t distinguish between serious and mild cases.

However, the usual caveats apply. This is a pre-print of a paper that has yet to be peer-reviewed. And in comparing the risk of myocarditis with the risk of being hospitalised with Covid only over 120 days, it doesn’t take into account the longer-term benefits; the vaccine is expected to offer protection against the virus for much longer than this. But the study will further question the wisdom of vaccinating children when the risks of the vaccines appear to have an inverse relationship with age — while older people are far more likely to suffer serious harm from Covid-19, it is younger people who seem to suffer the brunt of the serious side effects so far identified.

Moaning luvvies have a lot to learn from Brigitte Bardot

I missed Brigitte Bardot mania; by the time she retired from film-making at the age of 40 to concentrate on animal rights activism, I was only 13. But awhile back I saw a film of BB’s – La Verite, made in 1960, a courtroom drama which was her biggest ever commercial success in France and nominated for a Best Foreign Film Oscar – and was amazed at how good she was.

I joined a few Facebook fan pages. Unsurprisingly she is stunningly beautiful in all of them. But something stands out which differentiates her greatly from the alleged film stars of today. She pouts petulantly in studio shots, as befitted her image as a malicious minx who would un-man a fellow as soon as fleece him. But paradoxically, in the vast majority of off-duty or paparazzi publicity shots she seems at least serene – at best positively gleeful.

Which brings us to Hugh Grant and the Hacked Off mob of professional moaners

There’s one photograph in particular – from 1959, credited to Keystone Pictures, in which a mob of press photographers hustle to get close to Bardot as she is pressed up against a mirror. In both her face and her looking glass image, she looks not merely comfortable with the situation – but actually full of glee; she seems to find the situation hilarious. Many other photographs show her swimming and sunbathing on packed beaches with no apparent bodyguards.

In fact, she was the exact opposite of the *stars* of today who grin like cretins for official shots yet scowl like they’ve got cystitis and have just stubbed their toe whenever a non-approved photographer pops into view hoping for a bit of pap action.

Bardot was extreme in her lack of loathing for being observed by the media, but she wasn’t the only one. No matter what misery she was going through in her private life, Marilyn Monroe always had a good relationship with the press, so much so that Arthur Miller was able to shake off Communist accusations by announcing his engagement to her. A girl from extreme poverty, she had no airs and graces; she could be found in the New York phone book under that very name, once introduced herself on the telephone to fellow Actor’s Studio colleagues as ‘Marilyn – the blond girl in the back row’ and often hung out with the Monroe Six, a group of teenage fans who waited around her apartment building.

Liz Taylor and Ava Gardner would frequently go on gossipy bar-crawls with favoured hacks. Female films stars today are nowhere near as beautiful as these legendary women. But they act as if they are literally doing the public a favour by having their photograph taken. They have compared being papped to being raped (Kristen Stewart) or ‘how, like in war, you go through this bloody, dehumanising thing’ (Gwyneth Paltrow).

Which brings us to Hugh Grant and the Hacked Off mob of professional moaners who seem to believe that the destruction of a free press is a small price to pay in order for them not to be snapped looking a bit jowly. Grant had a right hissy fit recently, tweeting:

‘I don’t want my private life stolen by your creepy cameramen. And I don’t want my wife subjected to the Pinot Grigio sodden abuse from your tragic and unhappy readers.’

It’s actually really hard to achieve fame – so much competition for cushy, cushioned showbiz jobs – that anyone who hates publicity should have a serious talk with themselves, or their shrink, if they find out they actually don’t like being looked at. If you don’t want attention, there are masses of useful jobs you could do, helping humanity instead of showing off to them. If you can’t stand the heat of the Klieg lights, get back to the soup kitchen.

The 9/11 anniversary marks a painful moment for squaddies

The sweet salvation of the summer recess over, we returned to Sandhurst for our final term of officer training. It was 11 September, 2001 – a day that started with a hike in the sunshine and which came to define my time in the British Army. The events of 9/11 would lead to my own deployment in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the loss of dear friends and comrades.

Of course, on that September morning none of us knew how events 3,000 miles away – and the political decisions taken in the aftermath of those terrible attacks – would have such a momentous impact on our lives. After the buses dropped us off, the hike started jollily. The 90 or so young men on the cusp of their twenties, at the peak of their fitness and powers, who in three months’ time would commission as officers into the British Army to lead its soldiers, were more like a gaggle of schoolboys. We just had to walk, and it wasn’t raining! We couldn’t believe our luck.

But as the day progressed, text messages on Nokia phones told of an incident in New York involving the World Trade Centre and maybe even a passenger jet. At the hike’s end, the cadets and directing staff crammed into a small pub. Watching the images on the television news, how could we realise that the scenes unfolding before us would shape and manipulate our years in the army yet to come?

Things were obviously going awry

It was some time before my own involvement in the ‘war on terror’. In the months after 9/11, I was deployed to Kosovo after all the hard and dangerous work was done and the conflict’s darkest days, when pregnant women were crucified with stomachs slit open, were long gone. The restored peace seemed to indicate military invention – the type that inspired me to sign up to the army in the first place – could work. Tony Blair certainly came to believe as much.

In 2004, I was sent to Al Amarah in south-eastern Iraq. It was the tour of 1st Battalion the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment, made famous (and infamous) by the Battle of Danny Boy, resulting in the Al-Sweady Inquiry; the siege of CIMIC House, and a Victoria Cross for Johnson Beharry.

I absolutely loved it there and suspect I wasn’t alone. We all tasted ‘the kingliness of Friendship’ that C.S. Lewis described reflecting on his military service. ‘We meet like sovereign princes of independent states, abroad, on neutral ground, freed from our contexts.’ We felt invincible: we had the services of Basher-75, the American C-130 gunship raining down fire from the night sky. It’s nice to feel you have Zeus on your side. That feeling wasn’t to last: two years after my first deployment, I was sent back to Iraq, this time to Basra, to deal with improvised explosive devices coming from Iran. My previous enthusiasm was fading; the security situation was deteriorating dramatically and the British military weren’t helping; some of my best army friends had called it and left; things were obviously going awry.

Finally, in 2009 Afghanistan called, and I deployed with the Welsh Guards Battle Group to Helmand. Our commanding officer, Rupert Thorneloe, was a lovely man, but he would not return home: he was sliced in two by an IED. That tour broke me – and I was ensconced at headquarters. Even from that relative safety, it was clear we were in a dire situation. The talk of loyalty, integrity, discipline and courage drilled into us at Sandhurst felt like a distant memory.

‘Hell is total separation from God, and the devil is the will to that separation,’ Aldous Huxley wrote. In Afghanistan we tasted that separation.

Twenty years since that hike, now there are the mounting suicides among veterans, the suffocating rage, guilt and shame; words and events that still catch in the throat; therapy sessions for PTSD and moral injuries; ruined relationships and fractured families, life chances forever lost in the fallout of 9/11 and the path to Afghanistan.

Mercifully, many soldiers have found that these painful scars can be healed with love and support; there is hope. Of course, a sense of humour helps too. So on the 20th anniversary of 9/11, I’ll flick a middle finger and a smile to our generals and politicians; with the other hand, I’ll offer Raymond Chandler’s gunman’s salute of outstretched thumb and forefinger accompanied by a respectful nod to Terry Taliban. You licked us, but no hard feelings.

New poll puts Labour in front following Boris’s tax gamble

Boris Johnson’s health and social care levy may have won the support of his MPs but that doesn’t mean it’s a hit with the public. Overnight a new YouGov poll for the Times has been released which suggests that Tory support has fallen to its lowest level since the election. The poll puts Labour ahead of the Tories at 35 per cent, with the Conservatives on 33 per cent.

Six in ten voters said they do not think Johnson cares about keeping taxes low

As for Johnson’s plan to make the Conservatives the party of the NHS, there is some work to do before this becomes a reality. According to the poll, less than a third of voters said the Tories care about improving the NHS. Meanwhile there are signs that the decision to raise taxes is hurting the party’s reputation for keeping taxes low. Six in ten voters said they do not think Johnson cares about keeping taxes low.

Of course it’s just one poll so it’s hard to read too much from its findings. However, what it does do is point to the political risk for Johnson of his decision to raise taxes to fund the NHS. The risk is that he fails to get much credit for funding the NHS while losing support over the dent to the Conservatives’ reputation as the party of low tax.

It’s a particular problem for Johnson as there are plenty of Tory MPs who are nervous over the policy. With another vote due next week on the plans, those MPs who voted against or abstained will be further emboldened. Johnson’s relationship with his party is ultimately a transactional one — MPs are willing to back him and his agenda because they believe he is a vote winner. Anything that suggests otherwise leaves him vulnerable to future rebellions.

The snobbery of Roy ‘Chubby’ Brown’s critics

In a few hours’ time, comedy fans in Sheffield will take to the streets in protest. Their cause? Not Brexit, or climate change, but the decision to ban Roy ‘Chubby’ Brown from performing a gig in the city.

Chubby, who is not to everyone’s taste, is best described as the North’s answer to Bernard Manning or Jim Davidson. An earthy stand-up comic from Middlesbrough, he is perfectly prepared to talk, joke and trade raillery about race, religion and sexuality in a way few other performers are. This week, after 30 years of performing in Sheffield, he was told he is no longer welcome.

Sheffield City Trust, which runs various leisure sites on the local council’s behalf, summarily cancelled a planned performance by him in the city’s Oval Hall next year. The reason? The trust’s chief executive, Andrew Snelling, said:

‘We don’t believe this show reflects Sheffield City Trust values.’

Whatever the cause of the argument against Chubby Brown, he isn’t going away

For local Labour MP Gill Furniss this was welcome news. ‘This is the right thing to do. There is no place for any hate filled performance in our diverse and welcoming city,’ she said.

But to the council’s dismay, few others agreed – not least many local residents in Sheffield who rather like Chubby. The cancellation spawned a furious popular reaction; 35,000 people have now signed a petition demanding Chubby be allowed on stage.

This isn’t the first time that Chubby has had shows cancelled: performances in Ashfield, in Nottinghamshire, back in 2016, and Swansea a couple of years ago, were also called off. Does he deserve this treatment?

Chubby’s patter is referred to by his detractors as racist, homophobic and misogynist. But it’s worth spending a few minutes on YouTube to see what he actually says. There is certainly a never-ending flow of insults, ridicule and profanity; and religion, race and sexuality undoubtedly get their share and more.

But you will hear little, if any, malice, nor are there calls to hate, attack or ostracise anyone. More than anything, Chubby is a highly successful performer because he has a disconcerting ability to see things through his audiences’ eyes. For working-class audiences familiar with thinking, talking and joking about race, sex, sexuality and religion in an entirely unsentimental way with little respect for political correctness, his popularity is hardly a surprise.

True, none of this cuts much ice with progressive intellectuals. But leave such people – who are unlikely to be seen dead at a ‘Chubby’ show anyway – to one side. For any ordinary observer, ‘Chubby’ is just a low – if popular – comedian, most of whose bons mots you wouldn’t be very surprised to hear at the end of a long evening in a lively pub in a down-at-heel area.

Despite the City Trust’s expressed high-minded desire to uphold the values of the city of Sheffield, few if any see this comedian as a hate-monger of any kind. And that may well be the real problem. There is a strong suspicion that what drives people to distance themselves from him may be something rather different: namely, good old-fashioned snobbery.

Is the same kind of condescension with which Emily Thornberry viewed ‘White Van Man’ at work here? In the decision to cancel this show, there certainly seems to be a suggestion that protecting people from entertainers who pander to their low tastes is an obvious priority.

Whatever the cause of the argument against Chubby Brown, he isn’t going away. This morning a group of supporters who object to the efforts of the City Trust and local politicians to prevent his appearance will gather outside Sheffield City Hall.

Even if Chubby Brown’s brand of humour isn’t your cup of tea, you may well think Sheffield’s approach to it even less so. If you do, and you want to strike a blow against petty municipal one-upmanship, then you should back the protest.

The rise of British gin

Any avid gin drinker will know that botanicals are all the rage at the moment. From juniper to orange peel to lavender, the ingredients list on the backs of bottles are getting more elaborate by the day, and seemingly more exotic. But what may come as a surprise is the growing number of distillers who are sourcing all of their ingredients in Britain.

Tom Warner was one of the first distillers to incorporate homegrown botanicals into gin – a craze that has now taken off across the market.

As green-fingered geniuses unveil their glorious gardens at this year’s Chelsea Flower Show, the farmer and distiller will pour them a quintessential G & T, and he’ll be using his very own Warner’s Gin, while also distilling live, making his celebrated London Dry in the Jardin Blanc.

Warner has a strong association with the show, having presented a silver gilt medal-winning garden designed by Helen Elks-Smith in 2019, but this year the spirit takes centre stage.

As the gin category continues its resurgent march back into the home bar, simply adding a list of wacky ingredients to a label won’t cut the mustard with drinkers

As the gin category continues its resurgent march back into the home bar, simply adding a list of wacky ingredients to a label won’t cut the mustard with drinkers – particularly if you add mustard. Consumers now expect producers to tick sustainable boxes and provide explicable context for the cultivation and inclusion of their botanical choices.

Tom Warner was ahead of the curve on this and is so committed to his gin project he turned ten acres of his Northamptonshire livestock farm over to growing his own botanicals. With an initial focus on the native botanicals, the likes of Angelica root, lavender and lemon verbena have all foraged from the farm, and the wider ambition is to support the surrounding biodiversity and collect more ingredients locally, and sustainably.

‘My mum, Adèle, was an awesome gardener and cook and she grew a lot of plants for flavour in her gardens,’ says Warner. ‘In 2015, about a year after she died, I was stood in one of her gardens next to the distillery and realised we were not looking after it and it was still full of flavour. This was my field of dreams moment to build it. It was at this point I realised we needed to grow our own flavour.’

‘I believe we’ve been the blueprint for what craft gin is ever since. Right now, our horticulture for flavour requires two full time salaries, 120,000 plants, 750 trees, four years of my life, it’s taken some of my hair, made me older and now accounts for 10 acres of our farm, which will only grow over time.’

The Warner’s London Dry (£30, warnersdistillery.com) is becoming a benchmark for the style, fresh and bursting with flavour, placing juniper front and centre, it includes many botanicals foraged from the farm. As Warner points out, most gins require citrus peel, which a little trickier to cultivate in the UK, but by using discarded peels from a nearby fruit factory, the London Dry still retains sustainability credentials. The approach is working, and sales are booming for him.

So, just as is the case for those exhibiting at the Chelsea Flower Show, biodiversity and sustainability are buzz words in the wider world of gin. Juniper for example, has been historically shipped in from Europe but carbon footprint consideration has inspired new farming methods. Native juniper varieties thrive in the UK’s moorland or pine woodlands and since the botanical remains a key ingredient in gin and something that should remain ever present, it stands to reason other producers are harvesting from local sources.

Hepple Gin (£34.95 from whiskyexchange.com), produced at the Hepple Estate in Northumberland has launched a juniper propagation programme, supported by the National Park and Natural England. Every year the team plants out a few hundred seedlings that in due course will amplify the natural regeneration of juniper on the moorland.

As well as harnessing the local juniper, Hepple is made using cutting edge technological distillation techniques, with vacuum stills and carbon dioxide extraction processes delivering a juniper and citrus-forward spirit.

In the Peak District, Karl and Lindsay Bond have grasped trowels and donned knee pads to create Forest Gin (£49.50, masterofmalt.com). Gathering Peak District moss and ferns, flowers, spruce and pine from the Macclesfield Forest, they crush with pestle and mortar and add wild Bilberries, raspberries and blackberries along with organic juniper.

The worm has indeed turned in the organic soil for gin, and more is coming. Enthusiasts wait with baited breath and salivating mouths for creations from Howl & Loer distillery (https://howlandloer.com/) later this year. A combination of distiller and ecological gardener in Cornwall, the pair are also looking in their own back yard for flavours. Granted it’s a massive backyard, but the gin promises to be incredible.

So gin is coming up roses, and even with them.

Are China’s climate promises just a load of hot air?

Few cities in China represent the country’s addiction to coal more than Tianjin, where Alok Sharma travelled this week to talk about cooperation on climate issues. It sits on the coast of one of China’s most polluted regions, and its port is a key hub for trading 100 million tons a year of the stuff – that’s roughly 12 times Britain’s annual coal burn.

Chinese coal consumption is on track to increase this year by around ten per cent. To meet that demand, vast new open cast pits are being rushed into service in Inner Mongolia, China’s biggest coal production region, from where supplies are brought down the coast to Tianjin. There is a chance that Sharma might have caught a glimpse of the vast port, the piles of coal, or the traffic jam of ships waiting to dock, as he flew in. If so, it will have presented a far clearer picture of China’s commitment to a ‘sustainable future’ than the empty platitudes and vague promises of his hosts.

China has pledged that its greenhouse gas emissions will reach their highest point before 2030 and the country will reach carbon neutrality before 2060. Sharma, who will preside over the United Nations Cop26 climate summit in Glasgow in November, would like China to bring its targets forward. At the very least he was looking for more detail from special representative for climate change affairs, Xie Zhenhua, as to how China will achieve its targets. He got none – because China is taking a big leap in the opposite direction.

China certainly talks the talk on clean energy and sustainability

China is the world’s biggest polluter, responsible for 27 per cent of global emissions of greenhouse gases – and that’s about to get worse. It is opening new coal-fired power stations and increasing emissions at an annual rate that is greater than the savings of the rest of the world put together. Last year, coal plants with a combined capacity of 37.75 gigawatts were retired globally, more than half in the United States and European Union, according to an analysis by Global Energy Monitor, which analysis fossil fuel trends. During that time, China opened 38.4 gigawatts of new plants – that’s three times more new coal fired capacity than the rest of the world combined.

China has refused to budge on its target dates and refused to give detail as to how it intends to achieve them. This week, a prickly editorial in Global Times, a Communist party tabloid, said:

‘China has already announced its own climate road map and will stick to its own pace.’

Meanwhile, China is currently building new coal plants at more than 60 locations across the country, and local authorities are planning for still more. Far from providing a plan to work towards its 2030 ‘peak emissions’ date, it is as if China sees this as a finishing line in a race to build as many coal-burning plants as possible. It’s a construction frenzy that makes a mockery of the efforts of the rest of the world to reduce emissions.

The only bright spot is an apparent reduction in the number of new coal plants that China is financing in developing countries as part of its Belt and Road Initiative. This fall off appears to be more a result of the soaring price of coal and concern over debt than a change in Chinese policy, although Beijing might well present it as a concession.

China certainly talks the talk on clean energy and sustainability. It does generate more energy from solar power than any other country, and is seeking to corner the global market in many green technologies. But fossil fuels still account for 85 per cent of energy used, and coal represents 57 per cent of that.

Three days before Sharma’s visit, John Kerry, the US climate envoy, had his own meetings in China – also in Tianjin, which provided a useful insight into China’s tactics. Kerry had hoped that climate issues, of such critical importance to the whole world, could be divorced from prickly bilateral tensions. Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister told him to forget it, that climate cooperation could not be separated and that the US should ‘cease containing and suppressing China in the world.’

This suggests that China is prepared to hold its cooperation on climate issues hostage to concessions elsewhere. If that’s the case, Western negotiators should be very wary. Those who have sat opposite Chinese officials during negotiations over trade, cyber espionage and much more will be familiar with the tactics: playing the victim, veiled threats, vague promises, a lack of detail in any concessions – and ultimately ignoring any agreement reached.

Former president Barack Obama, a strong advocate of engagement with China, wrote in his memoir, A Promised Land,

that China’s economic rise has seen Beijing ‘evading, bending, or breaking just about every agreed-about rule of international commerce’. China has been a master of gaming that system to its advantage. It is naive to think that climate issues are any different.

Revenge and retribution: why we’re still watching Westerns

What is it about Westerns? They are the Chinese takeaway of film – they’re no one’s first choice, they haven’t been fashionable in living memory, and yet you never have to look too hard to find one.

One might also compare Westerns to cockroaches or sharks; pre-Jurassic survivors who have seen off much mightier beasts time and again scuttling from the dark shadows after the latest apocalypse. So here’s a prediction: Hollywood’s finest will be dusting off their chaps and six-shooters in years to come, long after the present glut of comic-book led mega franchises have hung up their CGI leotards for good.

But already a glance at the film schedules might indicate that Westerns are experiencing a bit of a bounce: Paul Greengrass’s adaption of Paulette Jiles’ novel, News of the World starring Tom Hanks was a streaming sensation of the lockdown and garnered eight Oscars and Baftas. Before that we also had John C Reilly and Joaquin Phoenix in Sisters Brothers in 2018 (adapted from Patrick deWitt’s novel) and then in 2017 Christian Bale returned to the genre for Hostiles, an uncompromising a Western as they come. This month, meanwhile, sees the release of Jane Campion’s new film, adapted from The Power of the Dog, a drama with a Western setting (1920s Montana), starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Kirsten Dunst.