-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

What the Bell Hotel case reveals about two-tier Labour

It’s a mark of the absurd legalism of Britain’s political system that after a month of fierce protests and years of government intransigence over asylum hotels, the future of the asylum system now rests on the whims of several judges in a dispute about planning permission. The Home Office and the owners of the Bell Hotel in Epping, Essex are appealing against the temporary injunction granted to Epping Forest district council last week, which ordered its closure as asylum accommodation after weeks of local protests.

All this really amounts to is a political excuse for the present dysfunctional asylum system

The judgement, which is due today at 2 p.m., will have ramifications for the entire asylum system: other councils, also experiencing protests like in Epping, may follow suit, potentially making it impossible for the government to continue housing asylum seekers in these venues. Currently, there are some 138 asylum seekers being housed in the Bell Hotel and 32,000 in hotels countrywide, out of a total of 111,000.

But while we await the ruling, one can already note the arguments the Home Office has had to put forward in this case, which have been deeply revealing of the government’s political priorities. Regardless of whether the Court of Appeal now rules in its favour, the legal action has occasioned a damningly explicit admission: that in the eyes of the Labour government, concern for ‘human rights’, the ECHR, and the interests of asylum seekers take precedence over the safety and security of the British people.

The fact of the appeal itself is striking given how loath this government typically is to challenge legal rulings. If there is one thing that is beyond sacred to the human rights lawyer in No. 10 and his personally appointed human rights lawyer ally Lord Hermer, it is the so-called ‘rule of law’. The new Attorney General set this out in his Bingham Lecture last year, where he named ‘judges’ and ‘lawyers’ top of the list of the ‘essence of liberal democracy’ and warned against populist talk of the ‘will of the people’.

Under the Hermer/Starmer double act, major foreign policy questions about arms licences to Israel and whether to join US strikes on Iran have been decided in terms of legalism, not the national interest. Slavish legalism also underlies the Chagos debacle. The UK handed over strategically important sovereign territory and paid Mauritius billions for the privilege because of the weight afforded to an ‘advisory’ opinion from a foreign court on which sits a former official of the Chinese Communist party. Domestically, meanwhile, cabinet ministers grumble that Hermer’s recent legal power grabs are hampering policymaking across government – one which is supposedly for ‘builders, not blockers’.

But now it seems the government is quite willing to fight a legal ruling – as long as it’s in order to prop up its reviled asylum system. Its submissions include straightforwardly political arguments about the headache it would mean for the government were the Bell Hotel to close. One Home Office official has even suggested that the dispute was a matter of ‘democracy’ – rhetoric Hermer himself would surely denounce were it to come from the right.

The government’s arguments betray an utter indifference to the safety of Epping’s residents. Edward Brown KC, speaking on behalf of Yvette Cooper, said:

The fact of criminal wrongdoing (and local concerns arising from criminal wrongdoing) is not a sufficient reason to require the immediate closure of asylum accommodation.

Indeed, though there are already allegations of serious crimes by three asylum seekers in Epping, Edwards insists that believing asylum seekers are more likely to commit crimes is ‘not a conclusion that can or should have been reached at all’ by Epping Forest district council. These are frankly disgraceful arguments when even one such avoidable crime is too many. Precisely how many sexual assaults will need to happen in Epping before there is ‘sufficient’ reason to close the hotel?

For a government eager to avoid the charge of being two-tier, another argument it makes is shocking. The Home Office concedes that Epping council has an interest in being able to determine whether or not there is an asylum hotel in its town – but insists that the ‘relevant public interests in play are not equal’ and indeed are ‘fundamentally different in nature’. The Home Secretary, for her part, ‘is taken for these purposes as representing the public interest of the entirety of the United Kingdom and discharging obligations conferred on her alone by parliament’. So the interests of the migrants, the government and its asylum system are deemed by Yvette Cooper to be in a higher tier of priorities – only of secondary importance is the right of Epping schoolgirls to feel safe as they walk around their town.

At times, the submissions drip with lawyerly condescension. ‘In the real world’, sniffs Edwards, ‘it is not realistic to think that the objective of the protests is compliance with the planning regime’. Instead, they were ‘driven by a range of grievances’, including ‘animosity towards asylum seekers’.

This line of argument only raises another double standard. The Home Office is happy to launch a legal action in service of a political end, but suggests it is somehow illegitimate for a council representing the interests of its citizens to do the same. In any case, so what if the protests are driven by ‘animosity’? One might retort that the government’s incomprehensible policy is driven by foolhardy sentimentality.

The key submission simply makes explicit a political reality which has long been clear to everyone: that Labour places the dictates of foreign courts ahead of the interests of British citizens. Unlike Epping’s interest in planning control, ‘the [Home Secretary’s] statutory duty is a manifestation of the United Kingdom’s obligations under Article 3 ECHR, which establishes non-derogable fundamental human rights’, it argues. ‘Non-derogable fundamental human rights’ – this high-sounding legalese is presumably expected to function as some sort of spell, ending the argument there by invoking the highest possible authority. All it really amounts to is a political excuse for the present dysfunctional asylum system: ‘We think the ECHR is very important and it is presently a line we don’t want to cross.’

The country knew that already, of course, but it is nevertheless quite something to hear the government say it so directly. The Home Office website proudly proclaims: ‘The first duty of the government is to keep citizens safe and the country secure.’ Yet faced with persistent local fury and concern, the Home Office is now lecturing the people of Epping that they have to accept a migrant hotel in their town because of the government’s ‘duty’ under the ECHR.

It is precisely this deranged, topsy-turvy state of affairs that the protesters are campaigning to be corrected. It’s now clear that the government actively wants it to continue.

Rayner’s stamp duty saving could cost her

Angela Rayner’s living arrangements are causing the Deputy Prime Minister a headache. The Daily Telegraph has today splashed on claims that Rayner allegedly ‘dodged’ £40,000 in stamp duty on her new £800,000 seaside flat in Hove, East Sussex, after telling tax authorities it was her main home. The paper reports that she removed her name from the deeds of her constituency house in Greater Manchester a few weeks before the purchase. By changing her primary residence, it meant she paid £30,000, instead of £70,000, in stamp duty. A spokesman for Rayner has said: ‘The Deputy Prime Minister paid the correct duty owed on the purchase, entirely properly and in line with all relevant requirements. Any suggestion otherwise is entirely without basis.’

There are two potential issues with these allegations. The first is the charge of hypocrisy. The changes are, as the Telegraph notes, ‘entirely legal’ but will, in their words, ‘raise questions over whether she has deliberately conducted her property affairs to pay less stamp duty and council tax.’ Given the way in which Labour in opposition relentlessly went after Rishi Sunak and others on tax, any suggestion of tax avoidance will inevitably be hurled back at them.

The second issue concerns electoral law. Rayner is, reportedly, registered to vote at three locations – in Manchester, Hove and London (where she has a ministerial flat in Admiralty House). The Tories have now accused her of breaking electoral law to avoid paying council tax on Admiralty House. The party is citing both election law and case law in their defence, arguing that she should be struck off the electoral roll in Greater Manchester on the basis that she does not ‘meet the legal tests for living there.’ A source close to Rayner told the Daily Telegraph: ‘Her home in Ashton-under-Lyne is her primary residence, and where she has been registered to vote for over a decade, entirely properly and within the rules.’

The Conservatives clearly hope to land a blow on Rayner, either by making her personally liable for her council tax bill on Admiralty House or by getting her struck off the electoral roll. While all this talk of homes is doubtless embarrassing for the Deputy PM, the mood in government remains broadly supportive. On today’s morning round her ministerial colleague Stephen Kinnock told LBC: ‘I do wonder sometimes about some of the newspapers that are out there that just seem to be constantly looking to dig out stories about the Deputy Prime Minister.’

That is doubtless true. But given Labour’s past grandstanding, it is hardly surprising that the Tories are now going after them using every trick in the book.

A dual crisis is looming for France

Financial crises are often linked to a political crisis. On 8 September, the French government will submit itself to a vote of confidence – which, by all accounts, it will lose. At issue is France’s parlous financial state, which a minority French government seeks to address. This week, French 30-year bond yields reached levels unseen since the Greek debt crisis in 2011, while the 10-year yield has surpassed present-day Greece’s.

France’s economy minister was quick to warn that France’s lamentable financial position could leave it facing an IMF bailout. This was intended to frighten MPs ahead of the vote rather than reflect reality. Greece was borrowing at near 30 per cent prior to its debt crisis and had a budget deficit of 15 per cent GDP, while France’s is 6 per cent. Parallels with Greece in 2011 are exaggerated. Yet debt markets can turn at the blink of a logarithm.

If François Bayrou’s government falls, an optimistic outcome is unlikely

Were that to happen, the European Commission would never allow an outside body alone to take control of a Eurozone member. As with the Eurozone crisis a decade and a half ago, a new ‘Troika’ would be appointed: IMF, European Central Bank and European Commission. Thirteen years ago I happened to be a member of that Troika called in to propose wholesale reform of the Greek public sector as the corollary for massive loans. Witnessing firsthand France’s leading role and unforgiving manner in ‘Task force for Greece’, it was clear how France’s attitude did not endear it to the Greeks. Like the French, they express their anger openly and carry historical grudges.

Demonstrations and riots were not the only signs of Greek frustration and humiliation. ‘Task force for Greece’ was nominally led by France and Germany. But the Greeks ran a very effective press campaign showing how German reparations owed to Athens from the second world war equated to Greek debt. Germany’s delegate to the task force had his German home firebombed (whenever I caught sight of him, he was always flanked by armed detectives). Germany discreetly left the ‘dirty work’ to France.

The French team was run by senior members of the French Finance Ministry. They set about the task with technocratic zeal. My brief was to lead on reforming the Greek university sector (having served a few years previously on a French prime ministerial commission for French university reform). The Troika austerity reforms were truly harsh. Fierce cuts to public sector wages and pensions, tax increases, privatisation of state-owned enterprises and labour market deregulation resulted. My bit part was cut short by Greece’s refusal to implement any reforms not proposed and directed by itself. That became the norm. Greek passive (and not so passive) resistance to the Troika austerity reforms and the consequent political turmoil led to Greece directing the reforms itself.

France’s prominent role in the Troika austerity measures should be a salutary lesson given its own financial predicament. With a 6 per cent budget deficit and national debt to GDP ratio at 113 per cent (predicted to rise to over 120 per cent), France is already operating at twice the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact requirements. In November last year, the country was placed in excessive deficit procedure (EDP). As a result, under Article 126 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, France is required to provide six-monthly plans to the EU Commission on the corrective action, policies and deadlines it will apply to return to a 3 per cent deficit by 2029, failing which astronomical fines could be imposed.

There is little chance France can comply with the plan. A political crisis is likely on 8 September. If François Bayrou’s government falls, an optimistic outcome is unlikely. Three fateful scenarios present themselves. President Macron could appoint France’s fifth prime minister in two years. But who would want the poisoned chalice of applying austerity measures with no possible majority in the present National Assembly? The President could call new elections as he did in 2024. But opinion polls suggest another minority government, albeit clearly dominated by the Rassemblement National. A third scenario would be for President Macron to resign. That would lead to a new RN French president, by no means committed to austerity measures.

Each of these options will seriously frighten financial markets, not to mention the European Union. Given the way President Macron has antagonised so many European leaders over the last ten years, not to mention its role in the Greek debt crisis, France should be fearful she is not forced into the indelicate hands of the Commission. Which country’s officials would march into Paris? Heaven forfend that I be invited to take part in a Greek-led ‘Task force for France’.

Topshop’s return doesn’t mean the high street is safe

You probably won’t see Kate Moss gossiping with a Spice Girl or two by the changing rooms, but for anyone nostalgic for the 1990s, there will be at least one treat to look forward to. Topshop is back. There is just one catch. Sure, it might be able to carve out a niche for itself. But in the face of a blizzard of tax rises, it can’t save the high street.

It is not exactly a return to the glory days, when its stores dominated every high street and suburban mall, but from this weekend you will be able to buy Topshop- and Topman-labelled clothes from a concession at the West End department store Liberty. A full-scale return to bricks-and-mortar stores is being hinted at by the chain, now owned by the online retailer Asos, and the Danish retailer Heartland. It is not completely alone. Uniqlo has opened its first store in Liverpool, and the fashion chain Mango is planning another 20 shops across the country.

A stagnant economy means that people don’t have any money to spend

It is easy to hype that up as the return of the high street after years of decline. And, in fairness, there are some signs that online shopping has stalled, and customers are returning to physical stores. The trouble is, it is not going to last.

It is only a few months since employer National Insurance contributions were increased and the threshold lowered, which left shops, which typically need a lot of modestly paid staff, facing a big rise in taxes. Business rates have been pushed up, and reliefs withdrawn, adding tens of thousands to a tax that has to be paid regardless of whether you are profitable or not. The living wage keeps being pushed up ahead of inflation, making staff more expensive to employ. And the police show no interest in clamping down on an epidemic of shoplifting that means up to five per cent of the stock has to effectively be set aside for theft every week. On top of all that, a stagnant economy means that people don’t have any money to spend.

High street retailers face a government that has no idea how business works, that despises entrepreneurs, and that is determined to wring every last penny of tax out of the economy that it can. So long as that is true, retailers face a relentless decline. A few fashionistas might be flocking to the new-look Topshop – but this doesn’t mean the high street is safe.

Four bets for the weekend

It’s always pleasing when the good guys do well in any aspect of life and in the racing world one man who is definitely falls into that category is Lambourn handler Jonny Portman. A friend of mine, who was a house guest at the trainer’s home for just one night a few years ago, observed Portman’s dedication to his horses.

At dinner, the host’s chair was vacant for much of the evening as he made a last tour of his 45-strong string, presumably doing the equivalent of tucking his horses up in bed and reading them a bedtime story. Early the next morning, Portman took my friend on to the gallops and talked through the characteristics and quirks of all of his horses as if they were his children. Just to be clear though, Portman is a devoted family man as well as a talented trainer.

Earlier this week Portman matched his best-ever seasonal total of 33 winners and that comes with an impressive strike rate of 17 per cent. He puts down his success to having healthy horses, great staff, supportive owners as well as ‘hopefully placing some of the horses in the right races and a big dollop of good luck too’.

His highest-rated horse is Rumstar who has won two Group 3 sprints this season and was a fast-finishing fifth in the Group 1 Coolmore Wootton Bassett Nunthorpe Stakes at York a week ago. Rumstar is likely to run next in a Group 3 contest at Newbury next month.

Another money-spinner for the yard for the past two seasons has been TWO TEMPTING who will tomorrow attempt to win the Virgin Bet Supports Safe Gambling Handicap (3.15 p.m.) at Chester over seven and a half furlongs.

Not only did Two Tempting win the equivalent race at the track last year off an official mark of just one point lower (95) but he is two wins from two runs over Chester’s unique twists and turns. Jockey Rob Hornby, who Portman rates highly and uses whenever possible, has been booked for the ride and he has won on six-year-old gelding twice before.

Two Tempting would prefer the ground to be on the fast side of good but he can handle good to soft ground if necessary because there may be some rain at Chester between now and the off. A draw in stall ten is not ideal but back him two points win at 7-1 with Paddy Power in the hope that Two Tempting can resume winning ways after four fairly moderate runs off higher marks.

Another trainer with his string in good form is Michael Dods. His horse GLENFINNAN is not one for the mortgage as he puts in plenty of poor runs among the good ones. Glenfinnan lines up tomorrow at Sandown for the Download The BetMGM App Handicap (1.50 p.m.) once again, like Two Tempting, having won the equivalent race on the card a year ago.

That was off an official rating of 93 yet, after a series of uninspiring runs since then, he can race of a mark of just 82 tomorrow. In short, if – admittedly a big if – Glenfinnan can recapture his best form, this five-year-old gelding is very well handicapped to win again. Back him one point each way at 11-1 with Sky Bet – that’s a point shorter than other bookies but with five places, not four.

There is plenty of other competitive racing at Sandown tomorrow where heavy rain over the past 24 hours means the ground is now riding on the soft side of good. In the Group 3 BetMGM Atalanta Stakes (2.25 p.m.) over one mile, AMERICAN GAL could outrun her odds.

Lambourn handler Ed Walker rates this three-year-old filly highly and she has won three of her six starts. Back her 1 point each way at 11-1 with Sky Bet – once again, that’s a point shorter than some other bookies but with five places, not four, in this competitive 14-runner contest.

Today I can’t resist backing an old favourite of mine, NORTHERN EXPRESS, in the Constant Security Services Handicap (4.08 p.m.) at Thirsk. Michael Dods’ seven-year-old gelding was fifth last time in a much hotter handicap than this, the Clipper Handicap at York, when his regular pilot was riding elsewhere that day. Paul Mulrennan is back in the saddle today and I can see Northern Express running a big race off an official mark of 98. Back him two points win at 5-1 with bet365, William Hill, Ladbrokes or Coral.

Last but not least, looking ahead to the Group 1 Betfair Sprint Cup at Haydock a week tomorrow, I am keen to back a horse at huge odds even though there will be more places available from bookies in eight days’ time.

NIGHTEYES, a four-year-old filly, is a course and distance winner who ran well when fourth in a Group 1 Queen Elizabeth II Jubilee Stakes at Royal Ascot at odds of 100-1. In a recent attheraces.com stable tour, her trainer David O’Meara revealed that the Sprint Cup is her next target ‘ideally with a bit of cut in the ground’.

With plenty of rain forecast over the next week, his wishes look likely to come true so back Nighteyes one point each way at 66-1 with William Hill, Sky Bet, Paddy Power or Betfair, all paying three places. Incidentally, this means I will be going into this race double-handed as I put up No Half Measures for this race two weeks ago.

This column’s winning run came to an abrupt halt at York last week but that was inevitable at some point. Next week I will be taking a look at the so-called ‘autumn double’: the bet365 Cambridgeshire and the Godolphin Cesarewitch, both run at Newmarket. The latter race is my favourite flat handicap of the year.

Pending:

2 points win Northern Express at 5-1 for the Constant Security Services Handicap.

1 point each way Glenfinnan at 11-1 for the Download The BetMGM App Handicap, paying 1/5th odds, 5 places.

1 point each way American Gal at 11-1 for the BetMGM Atalanta Stakes, paying 1/5th odds, 5 places.

2 points win Two Tempting at 7-1 for the Virgin Bet Supports Safe Gambling Handicap.

1 point each way No Half Measures at 12-1 for the Sprint Cup, paying 1/5th odds, 3 places.

1 point each way Nighteyes at 66-1 for the Sprint Cup, paying 1/5th odds, 3 places.

Last weekend: – 11.8 points.

1 point each way Celandine at 22-1 for the Nunthorpe, paying 1/5th odds, 5 places. Unplaced. – 2 points.

1 point each way Ya Mo Be There at 6-1 for the Ebor Handicap, paying 1/5th odds, 5 places. Unplaced. – 2 points.

1 point each way Talismans Time at 10-1 for the Melrose Handicap, paying 1/5th odds, 4 places. Unplaced – 2 points.

1 point each way Sea of Kings at 6-1 for the Melrose Handicap, paying 1/5th odds, 4 places. 4th. + 0.2 points.

1 point each way Twilight Calls at 12-1 in the Sky Bet Constantine Handicap, paying 1/5th odds, 6 places. Unplaced. – 2 points.

1 point each way Plage De Havre at 16-1 for the Ebor Handicap, paying ¼ odds, 4 places. Non Runner – 2 points.

1 point each way Majestic Warrior at 25-1 for the Ebor Handicap, paying 1/5th odds, 5 places. Unplaced. – 2 points.

2025 flat season running total: + 91.63 points.

2024-5 jump season: – 47.61 points on all tips.

2024 flat season: + 41.4 points on all tips.

2023-4 jump season: + 42.01 points on all tips.

2023 flat season: – 48.22 points on all tips.

2022-3 jump season: + 54.3 points on all tips.

Why Rachel Reeves will keep designing terrible taxes

I suspect most of us long ago gave up on expecting any humility from our politicians – indeed, the less impressive they become and the more impotent it is clear that they actually are, the more their God complexes seem to flare up. It’s almost like they think humans are characters in a simulator game – like the popular Sims franchise – who can be clicked on and commanded at will rather than rational actors with their own agency. Nowhere is this truer than in economic policy, where the fatal dominance of wonks who think too highly of theory and politicians who think too highly of themselves has resulted in almost no one thinking about how humans actually behave. This helps explain why politicians are so often terrible at designing taxes and anticipating how people may seek to avoid them.

It has been a problem in tax policy for centuries. Between 1696 and the 1850s, many thousands of homeowners decided they’d rather go without sunlight than pay the hated window tax. During the reign of Queen Anne, an attempt to target the rich by taxing luxurious patterned wallpaper similarly backfired when crafty homeowners began buying plain wallpaper and paying artisans to stencil their patterns on directly.

Much forecasting might as well be done with bird entrails for all the bearing it has on reality

No one invented more taxes than William Pitt the Younger as he attempted to fund the costly war with Napoleonic France (though I’m sure if they had enough time, Rachel and Torsten could give him a run for his money). In 1795, scrabbling around for easy revenue-raisers, Pitt began taxing the perfumed powder used to colour Georgian wigs. Rather than pay up, many more people decided they could do without their elaborate hairstyles. The policy is credited with ushering in new trends for cropped hair and hastening the end of Britain’s booming wig industry – as you can see by comparing portraits from the 1780s and the 1800s.

Still, Pitt was a brilliant man and would sometimes rethink taxes when it became clear that they were creating perverse effects. In 1784, he reduced taxation on tea from a staggering 119 per cent to 12.5 per cent and effectively destroyed its vast black market at the stroke of a quill pen, raising revenues at the same time. I’m not convinced, however, that our current government possesses the humility to admit their errors and change course.

One change currently being considered by the Treasury is an NIC increase for landlords in an attempt to boost revenue in the upcoming Budget. You detect that telltale misunderstanding of human nature and disdain for unintended consequences. Though some landlords may absorb the cost, many more would surely pass on the costs to their tenants via rent hikes or exit the sector altogether, thereby pushing up rents. Reeves and her team must know this but, boxed in by the PM’s earlier promises not to touch VAT, income tax, etc., they may be willing to overlook it, should it raise money without breaching their ‘red lines’.

Of course, there are rogue landlords, from whom tenants deserve protection. But when the bad behaviour goes the other way, the law already protects wrong-doers to a shocking extent – a fact that is, in itself, contributing to the exodus of small private landlords. A relative of mine was recently forced to instruct lawyers at great expense and apply to the High Court to evict a tenant who owes tens of thousands of pounds in unpaid rent arrears. On average, it now takes a landlord almost eight months to regain possession of their property after issuing a claim to court. The mere threat of the renters’ rights Bill coming into force has already impacted the market, with vast numbers of landlords selling up. Targeting landlords may be easy but it feels like displacement activity for the fundamental issue of supply and demand, an area where the government is notably failing, especially in the capital.

It’s almost like government officials haven’t moved on from the days of the Roman augury; much forecasting might as well be done with bird entrails for all the bearing it has on reality. The government’s initial forecast massively overestimated the sums raised by the VAT raid on independent schools, since nearly four times the number of pupils have been displaced into the state sector than anticipated. Their pledge to hire 6,500 new teachers has quietly been shelved (although Labour MPs seem remarkably unbothered by this, perhaps because the policy was always motivated more by class resentment than raising revenue). HMRC recently awarded their ‘expert of the year’ prize to the wonk who performed the costings on the family farm tax – a year before the policy actually takes effect, which prompts the question of how on earth they feel they can judge its success or failure now.

Other follies spring to mind. The high rate of income tax incentivises sole practitioners to pay themselves through dividends instead of pay packets. Excessive tobacco duty has now reached such a high rate that further increases are merely spurring black market and criminal behaviour without actually reducing smoking rates. A recent KPMG report found that one in four cigarettes consumed in the UK now comes from the illegal market, amounting to billions in lost government revenue. Despite Labour MPs’ attempts to explain why increasing employer NICs is not in fact a tax on ‘working people’ or a ‘jobs tax’, predictably, it has resulted in 157,000 fewer people on payrolls, while the OBR estimates that in the medium term, employees will bear about three-quarters of the NIC increase.

This is perhaps the worst thing about ill-designed taxes that ignore human behaviour; not only do they target the wrong people and the wrong things, they all but guarantee that the government will go back for more.

Reeves’s glum Budget briefings are hurting the economy

Rachel Reeves’s error before last autumn’s Budget might have been written off as the act of a ministerial rookie. She kept making us miserable by telling us about fiscal black holes and telling us that huge tax rises would be required to fix it – with the result that, come Budget day, the outlook for the government’s finances was worse than it should have been.

Reeves had helped to stall economic growth by damaging confidence. When you and I bleat on about how bad the economy is, nothing much happens. The same even applies to a shadow chancellor. But when you are in office, making the decisions, you have to be a lot more careful what you say. Talking down the economy can all too easily become a self-fulfilling prophecy if you start discouraging people from investing.

The economy is being damaged by the constant feed of bad news

And this year? Reeves seems to have learned nothing – she is doing exactly the same. Every day seems to bring yet another proposal to jack up an existing tax or introduce a new one. It is like being subjected to a whole decade’s worth of Today interviews with Torsten Bell, former head of the Resolution Foundation and now Reeves’s right-hand man at the Treasury – inventing new taxes has always been his speciality. And guess what? The drip, drip, drip of controlled leaks is beginning to have a serious impact on the behaviour of individuals and businesses whose help Reeves desperately needs to grow the economy.

Allan Leighton, Chairman of Asda, speaks for many when he calls on Reeves to ‘stop taxing everything in some way, shape or form’. His particular beef is with a proposal to increase business rates for large premises, such as supermarkets. As he points out, extra taxes on supermarkets will be passed on to consumers, which means more inflation, which in turn means higher debt repayments. It is the same with the numerous proposals for new or extra property taxes: they cannot help but dissuade buyers from committing to house purchases. That means less activity in the housing market, which in turn means lower receipts from stamp duty.

It used to be tradition that a Chancellor would go into ‘purdah’ in the run-up to a Budget – they wouldn’t talk about what tax rises might be in the pipeline. If they did, as Hugh Dalton found to his cost in 1947, it was a resigning matter. That tradition has gone out of the window in the past couple of decades. Instead, the practice now is to float proposed tax rises before the public through a series of anonymous briefings. Presumably the aim is to help prepare the ground so that the tax rises, when they are eventually announced, cause less of an impact. It also gives chancellors the opportunity to backtrack if a proposed tax rise goes down especially badly.

But it comes at a heavy price when, as Reeves has done this year, the tax proposals come so thick and so fast that they give the impression that absolutely everything is going to be taxed. Presumably when the day comes, the actual Budget won’t be as bad as the numerous briefings suggest it will be. Many people will feel a sense of relief when they realise they have not been hit after all. But in the meantime, the economy is being damaged by the constant feed of bad news. Who wants to do business or commit themselves to a large purchase when they are fearful of what is to come?

Purdah before the Budget wasn’t such a bad institution. Reeves should stop the briefings and realise that part of her job is to build economic confidence.

Was the Minneapolis shooting an anti-Catholic hate crime?

‘Don’t just say this is about thoughts and prayers right now,’ said Minneapolis mayor Jacob Frey, standing near the scene of yesterday’s Catholic school shooting in his city. ‘These kids were literally praying.’ I think he was trying to say, ‘This is no time for empty platitudes’ – or something similar. The words sounded horribly glib, though.

Of course, the killing of children distresses all good people, and Mayor Frey should be forgiven for an emotional outburst. There is something telling, however, about his kneejerk hostility towards the natural religious response to horror; his instinctive rage against the idea of a God who lets evil happen.

We are witnessing a concomitant outbreak of virulent anti-Catholicism in the land of the free

For a certain sort of metropolitan Democrat, Christianity is the impediment to, not the root of, justice. The secular liberal brain is trained to see Roman Catholicism, in particular, as wrong and harmful and needing to be stopped.

From what we think we know about the unhappy mind of the suspected killer, a boy called Robert Westman who wanted to be a girl called Robin Westman, it seems the same hostility – relatively harmless in a politician such as Frey – turned into something far darker. In an image widely shared on social media, we see what appears to be the machine-gun magazine clip he used to kill two children and injure 17 more. ‘Where is your God?’ is scrawled on the side. Westman, who went on to kill himself, had reportedly attended the Annunciation Catholic School – and his mother attended Mass at the affiliated Annunciation Catholic Church – that he decided to attack.

FBI Director Kash Patel has said his agency is investigating the shooting as ‘an act of domestic terrorism and hate crime targeting Catholics.’ Others argue that it is a mistake to confuse nihilism with politics or anti-religious ideology. Westman’s social media scrawlings suggest a warped, manically depressed and insanely incoherent outlook.

Yet western liberal loathing of Catholicism, which taps into a more traditional American Protestant phobia, has intensified in recent years. Today, mentally ill people often latch on to that hatred in a violent way. Since May 2020, some 400 Catholic churches have been attacked. According to the US Conference of Catholic Bishops:

Incidents include arson, statues beheaded, limbs cut, smashed, and painted, gravestones defaced with swastikas and anti-Catholic language and American flags next to them burned, and other destruction and vandalism.

In June this year, Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades, the chairman of the conference’s committee for religious liberty, wrote to Congressional leaders urging them to provide more funds for the protection of religious places of worship. Earlier this month, a vandal smashed windows and set fire to the door of the Christ the King Catholic Church in Flint, Michigan.

Catholics in America don’t expect or demand special protected-community status and no Christian wants to see sacred spaces turned into security zones. But there can be no denying that, as the latest reports suggest that American Catholicism is now entering a period of renewed growth, we are witnessing a concomitant outbreak of virulent anti-Catholicism in the land of the free. It’s an issue that the first American Pope might address in the coming days.

This article is from latest Americano newsletter. To subscribe click here.

Farage’s ECHR plans risk destroying the Union with Ireland

‘They’re tearing this country apart.’ I heard it in a pub last week. A man, with the light blue of the phone screen reflected in his face, was watching a reel. He waved the device at a nearby drinker. ‘You seen this?’ It was footage of the latest wave of small boat crossings.

A heated conversation ensued – the sort where its participants, though in agreement, rile each other up into sounding like they’re having an argument – decrying the political class. ‘They’re all the same,’ they said. ‘We need Farage to come in and sort it out.’ They agreed louder.

The small boats have become a metaphor for a broken political system

This week, Nigel Farage has finally made clear what ‘sorting it out’ would involve: withdrawing from the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and, consequently, renegotiating the Good Friday Agreement (GFA). He argues the ECHR is a barrier to effective border control. In his telling, Britain cannot get a grip on illegal immigration without breaking the legal ties that bind it to Strasbourg.

The GFA commits the UK and Irish governments to incorporating human rights protections, and the UK to incorporating the ECHR, into Northern Irish law. Leaving the Convention would mean different rights for those living in Belfast than in Dublin, breaking a fundamental principle of the Agreement. This would require renegotiation.

Understandably, Farage’s plans have attracted criticism. Hilary Benn, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, told me the GFA ‘brought to an end three decades of terrorist violence’ and warned that to talk flippantly about dismantling one of its core pillars shows Farage ‘hasn’t got the faintest idea about the consequences’.

To jeopardise the Agreement, Benn said, would not only be ‘dangerously irresponsible,’ but would disrespect ‘all those who helped to bring about the peace that the people of Northern Ireland now enjoy.’

Farage’s plans also threaten to dismantle the Union – the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. His announcement comes at a moment when the republican movement feels increasingly emboldened.

I recently spoke to a former IRA bomb maker, now a prominent Sinn Féin member, about the possibility of Northern Ireland breaking away from Great Britain. ‘We don’t need to do anything,’ he told me. ‘Westminster will do it for us.’ He was referring to what he views as the ineptitude of the British government. That quiet confidence is telling.

Once, republican hopes hinged on the assassination of politicians and the murder of civilians. Today, it is driven by the failure of the British political system to deliver for its people – not least on immigration.

Indeed, it is this frustration with the Westminster establishment that is driving many on the British mainland towards Reform. The small boats have become a metaphor for a broken political system.

Famously, David Cameron pledged to reduce net migration to the tens of thousands. That target evaporated and in 2024 a net 431,000 came to these shores. May, Johnson, Truss, Sunak and now Starmer – each has failed to get a grip. Public frustration is justified.

All of this has led to a growing view that the self-proclaimed outsiders Reform, with their plans to leave the ECHR, are the solution. In the irony of ironies, it may be the great British patriot Nigel Farage, who once misguidedly signed off a Cameo video with ‘Up the ‘Ra’, who might oversee the end of the Union and a united Ireland.

Farage’s announcement comes at a time when Sinn Féin is already renewing calls for a referendum. The party is electorally successful on both sides of the border. Culturally, too, republicanism is on the front foot: the rap group Kneecap now makes headlines and fills venues. Irish rebel music, once the preserve of a sectarian diaspora, has entered the mainstream. Farage’s talk of renegotiating the GFA gives that movement new material.

The Agreement is far from perfect. I’ve written before about the enduring reality of Belfast’s peace walls, the literal barriers that still separate communities 27 years on. But while the Agreement may not have fully healed Northern Ireland, it has – for the most part – stopped the bleeding. It replaced armed conflict with political compromise. And it endures, not because everyone loves it, but because nobody has yet offered a better alternative.

None of this is to deny that immigration is an important issue. It is. The sheer scale of arrivals in recent years has undoubtedly placed strain on public services already stretched thin. Voters are right to demand action. But we must ask: is this challenge so existential that we are willing to risk sacrificing the Union to solve it? If the answer is yes, Nigel Farage may well be remembered as the man who tore it apart.

The folly of blaming boomers for France’s financial crisis

Ministers are packing up their offices. Emmanuel Macron’s government, desperate to shift the narrative and rally support ahead of its confidence vote on 8 September, is now blaming baby boomers for the financial crisis. Prime minister Bayrou is reframing the crisis as the result of decades of policies favouring older voters: generous pensions, protected benefits, early retirement – all funded at enormous cost to younger generations.

Bayrou is desperate to shift attention away from his government on the brink and onto a generational blame game for France’s slowing, debt-burdened economy

In an appearance on TF1’s main news bulletin on Wednesday night, Bayrou accused the post-war generation of driving the country into its debt spiral, saying that borrowing had been piled up ‘for the comfort of certain political parties and for the comfort of the boomers’, and warning that ‘the youngest French will have to pay the debt their whole lives’.

It was part fiscal morality tale, part political diversion. With the government heading towards almost certain defeat, Bayrou is desperate to shift attention away from his government on the brink and onto a generational blame game for France’s slowing, debt-burdened economy.

The crisis began on Monday, when Bayrou announced that the government would put its survival to a vote. The decision came from Macron himself. The aim was to regain control of events: the Bloquons tout general strike on 10 September threatens to paralyse the country, and the opposition was preparing a no-confidence motion to capitalise on the unrest. Macron calculated that by forcing a vote first, he could seize the initiative, daring opponents to topple the government while warning markets of the chaos that would follow.

But the execution undermined the strategy. Bayrou didn’t consult the leaders of the main parties before announcing the plan, later offering the weak explanation that ‘most were on holiday’. That made both Bayrou and Macron himself look detached from political reality. Within minutes, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally, Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s France Insoumise, and the Socialist party all announced they’d vote against the government.

What was meant to project strength has instead exposed Macron’s isolation. The Élysée had hoped to box its opponents into abstaining, fearing the political fallout from destabilising the government given the country’s economic fragility. Instead, Macron’s gamble has achieved the opposite, uniting parties that rarely agree on anything around one thing: bringing his government down.

By framing the debt crisis as generational injustice, Bayrou is trying to move the debate onto something the government can defend – structural deficits, unsustainable borrowing, and the burden on younger taxpayers. It’s a high-risk tactic. The boomers are a powerful voting bloc, courted by governments of all stripes for decades. Casting them as the villains of France’s economic malaise alienates an electorate Macron cannot afford to lose. Worse, it looks like desperation from a government losing control.

On Thursday, under pressure, Bayrou tried to walk back his comments. Speaking to journalists, he insisted he’d been misunderstood, while doubling down on the underlying message: that older generations, as ‘parents and grandparents’, bear a moral duty to help resolve the debt burden rather than leave it to the young. Perhaps realising the damage he’s done, he’s shifting his narrative from who’s to blame, to who should help. Nevertheless, clips of Bayrou have gone viral on social media, where he clearly frames the boomers’ comfort at the expense of younger generations.

The Élysée is in damage-control mode. Bayrou has said he is ‘open to all necessary negotiations’ over the budget. He’s holding talks with centrists and moderate Socialists, hoping to persuade some to abstain rather than vote against the government.

France faces a €44 billion fiscal gap, rising borrowing costs, and investor unease. Billions have been wiped off the value of French bank shares, bond yields are climbing, and markets are beginning to price in instability. The Bloquons tout strike on 10 September is going ahead regardless of whether the government falls or not, with shutdowns planned across transport, schools, and energy.

The far left is on the war path. Relishing the chaos, Jean Luc Mélenchon is pushing ahead with his motion to remove Macron. While it looks increasingly likely Macron’s government will fall, the president is for the moment expected to survive a motion to impeach him. The bar for impeachment is higher than for removing his government, requiring a complex process involving both houses of parliament. But Macron has been weakened. He is retreating into foreign policy and refocusing on the war in Ukraine. Under the French constitution even if his government falls, the president continues to manage foreign policy and the military.

Bayrou’s decision to blame baby boomers for France’s debt crisis was a calculated political move which backfired. Designed to shift attention from his government on the brink, Bayrou reframed the financial crisis as the result of decades of policies favouring older voters. The government alienated a powerful electoral bloc that Macron cannot afford to lose. It’s also invited awkward questions about why successive Macron governments have gone along with this. By blaming the boomers, Bayrou is desperately trying to hang onto office, but his strategy is at Macron’s expense.

Taylor Swift is saving America

Elon Musk and Taylor Swift fans rejoice! America’s birthrate is saved! News of the engagement between America’s reigning sweetheart, Taylor Swift, and jock, Travis Kelce, can mean only one thing: a millennial marriage boom is upon us. And with it, natalists will hope, an impending baby boom.

I’m no Swiftie. Nor am I one of those men who’s organised his entire political identity around hating the singer. Still, I can’t deny that I feel uplifted by the jubilation erupting across the US and beyond this week. Why? Because Taylor and Travis are taking a stand against pessimism. America’s permanently heartbroken oldest daughter has escaped her fate (for now). These are people taking the leap! Committing to something! How exciting is that?

Talking about the birthrate is so passé. Cringe, even. I have no desire to weigh in (and wouldn’t be, had my editor not twisted my arm into writing this piece), even as I acknowledge that it poses a serious problem for the nation’s future. So too does the hesitancy toward marriage and even dating among the young. But any millennial or Zoomer forced to brave the dating market in recent years knows the battle of the sexes has gone nuclear. An overriding pessimism about the value of relationships, with all their potential for pain and suffering, has metastasised; in heterosexual relationships, a casual two-way hatred of the other sex has also become disturbingly commonplace.

Enter Travis and Taylor. Their engagement post, which at the time of writing has racked up more than 30 million likes, is surprisingly suburban. It looks like an engagement backdrop I’ve scrolled past a thousand times. There is little extravagance in it (excluding the boulder of a diamond). But they’re making a marriage proposal – a daunting prospect – appear attainable, and more than that, mundane. There’s something lovely about that everydayness that shouldn’t be lost on the billions of people who see it.

Commentators will quickly point out that this engagement is timed eerily close to the announcement of Taylor’s new album, The Life of a Showgirl. Maybe this is all stage-managed opportunism, then. Probably. But everything our celebrity class does is stage-managed opportunism, and this example is at least subversive for how surprising and against-the-current it is. The underlying message: take a chance. Ask her out – if not on your family sports podcast, then at least at the bar. Certainly this is less damaging to the American national psyche than, say, the public dissolution of Kim Kardashian and Kanye West’s union.

Conservatives in the US will quickly claim the Tayvis union as a win for their political camp. But Taylor mastered the art of vague messaging long ago, and as is often the case, there’s something for everyone. With the announcement, Taylor seems to be telling her fans that you can have it all – the marriage and the career (not exactly a New Right talking point). Anyone with an internet connection, which is to say everyone, will recall that she was most recently in the news for the announcement of Life of a Showgirl, on the cover of which she appeared very scantily clad. Contrast this with the image of her this week in a walled-off garden wearing a modest dress. You can be a showgirl and a happy fiancée, she seems to be saying. Is this tenable? Will it end in heartbreak? Who knows. But it’s a nice thought.

Perhaps there are valuable lessons here for both sides in the battle of the sexes. Women: take a chance on the idiots. Men: don’t be so afraid of a go-getting woman

Kelce, whom I suspect can’t read, is certainly marrying up. He’s no slouch, of course. NFL-loving men across America have had their hearts repeatedly broken by him and the Kansas City Chiefs on too many Sundays in recent years. But his fiancée is the biggest star in the world. Perhaps there are valuable lessons here for both sides in the battle of the sexes. Women: take a chance on the idiots. Men: don’t be so afraid of a go-getting woman.

In addition to celebrating the couple’s big win, we can quietly celebrate the knock-on wins coming our way. Travis, we can only hope, will be thoroughly distracted by the wedding planning. This should hinder his on-field performance, and America therefore may soon be released from the tyranny of the dominant, evil Kansas City Chiefs. Also, America, allergic to monarchy, doesn’t have royals. So this union will be the closest thing to a royal wedding we have over here, and everyone loves a good wedding party.

Maybe I’ll feel more pessimistic about all this later. It seems likely I will. But who wants to pooh-pooh a couple who’ve just got engaged? Even the Gossiper in Chief has caught the cheeriness bug: ‘I wish them a lot of luck,’ Donald Trump said during a cabinet meeting. ‘I think he’s a great player. He’s a great guy. And I think she’s a terrific person.’

For now, we owe Taylor and Travis. Optimism is back – at least for this week.

A version of this article first appeared in The Spectator World.

My gastronomic tour de France

On holiday in the Dordogne, I face an annual dilemma. My weekly Any Other Business column ruminates on the financial world with occasional restaurant tips to lighten the tone – and many readers tell me they frankly prefer the menus du jour to the boardroom dramas. My difficulty is that in a single page of The Spectator there’s never space to do justice to both. Last week, I ended up cramming seven restaurants into one short paragraph, a paltry snack where I’d like to have offered a banquet. So here’s my 2025 tour de France, as I called it, at somewhat fuller length, perhaps one of these days to be super-sized into an entire guidebook.

This set of recommendations, I should explain, come mostly from British readers and friends in other parts of France. We’ll get to my own selections towards the end but let’s begin with lovely Catriona Olding, widow of Low Life’s Jeremy Clarke, who tells me the vitello tonnato is excellent at Le Bistrot de Lou Calen in her Provencal village of Cotignac – and she and her daughter ‘ended up in La Tuf bar next door until 1a.m.’.

While we’re in the Provence region, an artist and winemaker friend says La Bartavelle (named after a local partridge) at Goult in Vaucluse is a hidden gem offering rabbit, pigeon and ‘even pike’ washed down with rosé such as La Couloubre from nearby slopes. Or go upmarket to La Bergerie de Capelongue at Bonnieux in Luberon, where the de facto dress code is soirée blanche (all white, men as well as women), the cocktail du jour is a boulevardier and the truffle pizza is ‘uniquely delicious’.

Not all of southern France is so lucky, mind you. A London legal eagle with a hideaway in the mountainous Cevennes emails: ‘This has become a bit of a gastronomic desert’, but the best place within 100 kilometres ‘was and probably still is La Mirande in Avignon, behind the Palais des Papes’ – a grand old place indeed, where I see you can order an eight-course tasting experience for everyone at your table at €195 per head, or go €39 for a simpler menu de la semaine.

We’re bypassing Paris on this tour (though I’ll throw in a quick mention of Le Trumilou, a cheap and cheerful people-watching spot on the Quai de l’Hôtel de Ville) and heading straight to Normandy, where a bon vivant chum tells me Le Drakkar in Deauville is a must for the horseracing crowd who descend for the August bloodstock sales as well as for international jet-setteurs generally. ‘And the black cod is magnifique.’

His other favourite this season is at Veules-les-Roses, a picturesque seaside village discovered in the 1840s by the notorious actress Mademoiselle Anaïs of La Comédie-Française: ‘La Source is a charming new restaurant with the most delicious oysters in Normandy, patronised by chic Parisiens who’ve had the good sense to avoid St Tropez.’

‘Patronised by chic Parisiens who’ve had the good sense to avoid St Tropez’

South-westwards again, to my cousin who’s a Good Life-style smallholder in Charente. Her pick is L’Estaminet du Chateau at Rochechouart, where the more challenging menu choices include carpaccio of pig’s trotter and chorizo in chimichurri sauce. And at last back to the Dordogne, where there’s such a buzz in the best places this summer that’s it’s often hard to book tables — even though my pessimistic French neighbour says ‘La France est ruinée’. But hell, if the going’s a bit tough in the wider economy, what better than a substantial lunch at L’Auberge de la Nauze at Sagelat, one of those places where the giveaway is the line-up of white vans in the car park at midday, indicating that local tradesmen consider it value-for-money good eating. If you like it and you’re brave, the whole place, like many businesses round here, is up for sale.

Finally, further south over the hills in the Lot valley, my housemates adore La Récréation, set in an old schoolyard in the village of Les Arques, where every meal begins with a sharp little bowl of gazpacho. And a last one from me, newly discovered, Le Vinois at Caillac, an oasis of calm among the vineyards of Cahors.

Here lunch was just €19 for fish and a fine apple tart. But the sting was in the credit card terminal, which asked me whether I’d like to add a tip of 10, 15 or 20 per cent, or nothing. In France, service is a matter of pride and tipping isn’t part of the culture, though satisfied diners sometimes slip a small note under the coffee cup. The machine’s question would surely offend traditional French customers, so I’m wondering whether it was programmed only to ask foreign cardholders. Politely I tapped ‘10’, but I hope this is not the start of a trend: if so, I’ll certainly be fuming about it in Any Other Business.

The unstoppable rise of Send

As students go back to school this September, headteachers across the country are being forced to confront a system in crisis. While children reconnect with their friends and swap stories of the summer holidays, an ever-increasing number will have a little ‘S’ next to their name on the register – for Send, or Special Educational Needs and Disabilities.

Startlingly, one in five students in England are now recorded as having Send. Policy Exchange’s new report, Out of Control, finds that the number of children given Education, Health and Care Plans (EHCPs) – designed to support those with the most severe needs that schools cannot normally provide for – has increased by 83 per cent since 2015. As a former teacher, I saw this spiralling crisis first hand.

This has come at a tremendous cost. Half of all extra schools spending in the last decade has gone on Send. £11 billion will be spent this year – with taxis for children with Send set to cost more than £1 billion alone by the end of the decade. The system is at breaking point, with three-quarters of England’s councils facing bankruptcy over Send costs.

£11 billion will be spent on Send this year – with taxis for children with Send set to cost more than £1 billion alone by the end of the decade.

The popular consensus that the unstoppable rise of Send among our children is the product of better awareness and diagnosis has blinded policy-making for too long. In reality, while mental health and neurodivergence remain fundamental challenges for many young people, the system increasingly draws in many who do not need a label and do not benefit from having one – at terrible human and economic cost.

Child development is messy. Yet the desire of parents and teachers to ensure young people are happy and healthy has too often spiralled into an urge to problematise that runs counter to children’s interests. We used to be comfortable accepting that sometimes children might feel down or upset, or struggle to keep up with their peers in class for a period. Now widespread concern about mental health means that if you feel anxious, you must have anxiety. If you get restless in lessons, you must be struggling with ADHD. Yet a 2018 study at Cambridge University found that 25 per cent of children diagnosed with Send were in fact age-typical.

Worse still is an incentive structure that encourages families to seek out labels for their children in return for a host of benefits. Middle-class dinner party conversations now turn on what diagnoses will unlock extra time in exams. Send-based exam adjustments are twice as common in the independent sector as in state schools. The unlimited funds that can be unlocked by EHCPs have started an arms race of parents wanting to access more support for their children – crowding out those with genuine needs.

This diagnosis-seeking behaviour clashes with a Send system dominated by limited knowledge, poor evidence and woeful outcomes. Thousands of schools are offering forms of Send support without any evidence base in their favour. One girl I taught would insist she could not read without the aid of a transparent yellow slip – a ‘coloured overlay’, a dyslexia intervention which, I would subsequently discover, had been debunked in the 1980s. Yet Policy Exchange found these are still used in nearly a third of sample schools.

Many children in the Send system face very real difficulties with learning. Yet more and more young people are being unnecessarily labelled and then taking those labels to heart. I vividly recall one boy who, despite being very bright, had been laden down with supportive technology at the insistence of his overbearing mother. Once, when asked to complete a simple numbering task, he insisted he could not hold a pen and – despite being able to write very well, as I later found out – insisted on drawing the whole worksheet out on his tablet, rather than doing the task in front of him.

When a child is told they cannot do something by adults they trust, they tend to believe them. Instead, as Bridget Phillipson and Wes Streeting have both argued, these children require ‘much-needed grit’. The system needs to focus on what children can do, rather than damning children with Send through the poverty of low expectations.

Tinkering around the edges will not deliver the change we need. We cannot afford to throw more money into the pit, supporting a system saturated with demand which means help often does not reach those who need it most. Instead, we must scrap the perverse incentives, insist on good evidence and address over-medicalisation.

EHCPs should no longer come with the tantalising promise of unlimited funding. Schools should be required to commission only Send interventions that are cost-effective and backed by strong evidence – in the way that hospitals do for medical treatments. Resources need to be made available to help children earlier, breaking the link between diagnosis and support.

These proposals are radical but necessary. We cannot afford to remain locked on a path that is unsustainable and unaffordable – and which betrays the very children the system claims to help.

Why has Putin gone after the British Council in Kyiv?

Is Moscow targeting European institutions in Kyiv in the hope of ‘sabotaging peace’ as Keir Starmer has claimed? Putin probably thinks he’s actually doing the opposite.

Last night saw another massive attack on Ukraine: 31 missiles and 629 drones, of which five and 66 got through the country’s air defences, respectively. Many hit Kyiv, where 15 civilians were reportedly killed, including four children. However, particular diplomatic furore has been generated by the two missiles which, at 5:40 a.m., hit a block on Zhylyanska Street, south-west of the centre. This block, stretching across the adjacent Korolenkivska Street, houses both the British Council offices and also the European Union delegation offices. Both were damaged, although fortunately without fatalities, although a night security guard at the British Council was hurt.

Putin appears genuinely to believe the UK and Europe are not allowing Kyiv to ‘see sense’

The response has been predictable and understandable. Starmer beat his breast that ‘this bloodshed must end,’ and called these ‘senseless Russian strikes.’ The EU’s foreign policy chief, the fiercely anti-Moscow Kaja Kallas, trumpeted that ‘while the world seeks a path to peace, Russia responds with missiles,’ with a ‘deliberate choice to escalate and mock the peace efforts.’

The strikes on civilian targets are clearly indefensible, although some were likely not deliberate, but the result of missiles and drones being hit by air-defence fire (they or their debris has to come down somewhere), being poorly targeted or sent off course by jamming. None of this in any way excuses Moscow for its willingness to send ordnance into towns and cities, but it does mean that it can sometimes be difficult to be certain what was a specifically targeted strike intended to send a message and what was incidental catastrophe.

There can be little such ambiguity here. The block was hit by two missiles, whether Iskander ballistic missiles or Kh-101 cruise missiles. These are accurate weapons, and the fact that two hit in quick succession makes it extraordinarily unlikely that this was just bad luck.

However, the talk of Putin launching such attacks to sabotage or even mock the peace process – such as it is – is political rhetoric. If Putin doesn’t want peace, he just can keep fighting; if he wants to pretend to accept the western notion of how to make peace, he can stop the attacks and engage in a performative display of delegations, proposals and fine rhetoric. Instead, he is engaging in negotiations à la Russe. Putin’s refusal to countenance a ceasefire before any peace talks, which would give Kyiv breathing space, is because he believes in war and peace – in continuing military operations to pile on pressure, even if any meaningful negotiations take place.

Putin is under some pressure himself, especially as the Russian economy slides towards recession, but this is not enough to threaten his position or force him to end the war. Yet it is enough that he appears at least willing to see if a deal which suits him – by allowing him to trumpet his success in defying Nato and ‘saving’ eastern Ukraine – is on the table. But he is waiting for the other side to make a move and signal a willingness to accept his terms, and perfectly willing to walk away if this doesn’t happen.

In this context, whom does he see as the main obstacles to a deal? Europe and the UK. Given Putin’s continuing refusal to see the Ukrainians as having genuine agency, he appears genuinely to believe the UK and Europe are not allowing Kyiv to ‘see sense.’ The notion of a ‘coalition of the willing’ and talk of a western ‘peacekeeping force’ numbering tens of thousands of troops may look like a fantasy, but to the Russians it demonstrates two things: a continuing determination to see Nato troops in Ukraine, and an Anglo-European desire to derail any potential deal by making demands they know full well Putin will reject. The idea that Boris Johnson did the same in April 2022 when he visited Kyiv in the wake of talks in Istanbul is largely mythical, as Zelensky was already planning to reject their terms, but it remains powerful in Moscow.

The British Council was banned in Russia in June, accused of being a front for espionage and subversion. With its offices and the EU delegation so close together, how better symbolically to warn both London and Brussels to back off? Here’s the irony: in Putin’s ruthless bloody-handed diplomatic style, he presumably thinks that he is furthering the prospects of peace rather than sabotaging them. Just peace on his terms.

Man Utd vs Grimsby is what football should be about

Poor old Ruben Amorim. The sight of the hapless Manchester United manager cowering in the Blundell Park dugout seemingly praying that his billion-pound team could somehow scrape through on penalties against fourth-tier Grimsby in the Carabao Cup last night is now indelible. Perhaps only the tear drenched face of Rachel Reeves cowering in her own dugout in the House of Commons will compete this year for visual power. As you are probably aware, Amorim’s invocations were to no avail: after a marathon penalty shoot-out United lost. Though it wasn’t just Grimsby but football as a whole that was the winner.

Last night’s game was a glorious evocation of all that was once great and maybe still is about British cup football

For last night’s game was a glorious evocation of all that was once great and maybe still is about British cup football. We had an ancient old stadium, housing a raucous and rude home crowd, flourishing their fishy inflatables (piscine symbolism and references abounded) in a David vs Goliath encounter played at a furious intensity in magnificently unseasonal British weather. There was even a pitch invasion at the end after the slingshot/penalty shoot-out finale. If only the trespassers had been wearing parkers and flared jeans and sporting long lank unwashed hair the image of a 70s-era giant-slaying would have been complete.

OK, let’s not get carried away, it was the distinctly un-storied Carabao (I don’t know what this is and refuse to find out) Cup rather than the true jewel of English football the FA Cup at stake, and United have been a hot mess for ages, so if any team was ripe for this kind of ‘battering’ then they were. But this was no fake, the gulf, on paper, between the sides was vast. And there was no suspicion of a certain erm… lack of commitment (see Plymouth vs Liverpool last February) that sometimes characterises these upsets. Manchester United are so starved of success that they are obliged to take this lesser tournament seriously. The ‘stars’ were out and appeared at full throttle, it’s just that United at full throttle is often half cocked these days.

Apart from being cracking (free-to-air!) entertainment, last night’s game should serve as a salutary lesson. The football authorities are forever mucking about with our tournaments, cramming the calendar and trying to gouge out every last penny in a way that ultimately wounds the game. Every year formats and financials are tweaked so that it gets harder and harder for clubs from the lower ‘tiers’ to compete with the giants. The dominance of the Premier League and Champion’s League in the thinking of the big clubs has risked rendering domestic cup football an afterthought, or tiresome obligation to be treated as a chance to ‘experiment’ or only half-heartedly engage in.

Which kills the game, making it bland and predictable, and ultimately perhaps, less profitable. There is evidence that the Premier League has peaked in terms of revenue-generation and is starting to decline. There may be many reasons for this: the uniformity of playing styles, high turnover of players with not even the remotest connection to the clubs they join, the absence – to the point of it seemingly quaintly anachronistic – of such concepts as loyalty (Isak) are all relevant. But lack of jeopardy, the tiny pool of ‘winners’ is surely foremost, which has led to a situation where last night’s drama feels not just like a welcome, entirely pleasurable reminder of what we all found so thrilling about football in the first place but should serve as a wake-up call to the money men as to what makes the game profitable in the long run.

The true lifeblood of the game is stories, which require teams like Grimsby to now and again beat teams like Manchester United. That is what keep fans engaged and committed, and coming back for more. It also maintains football’s wider, incidental but important, social functions as a benign arena for displays of local pride, provider of cathartic experiences and a channeler of frustrations. Where once predominantly men went to football on a Saturday partly to work off the aggression of a week spent in manual toil, now everyone goes along. But we still need the heroes, and especially the villains to serve as proxies for our broader frustrations. And Man Utd make great villains.

It also keeps our spirits up and inspires good humour, albeit of the schadenfreude variety. Manchester United fans should brace themselves. The jokes will keep coming and they will sting a bit, for a while. But it’s all part of the fun. Here’s one to finish: Manchester United fan goes into a travel agent and asks for a holiday recommendation. ‘You can’t beat Grimsby at this time of year’ comes the reply.

Rylan is a sign the immigration debate is shifting

I’ve always been quite fond of Rylan Clark. No, that isn’t quite true – when his terrifyingly toothsome grin appeared for the very first time on TV, as a contestant on The X Factor back in 2012, I did grimace at this apparently air-headed Katie Price-meets-General-Zod wannabe. As often happens with reality TV, despite what its critics say, prolonged time spent in his screen company revealed a quite different person. As he says in his own bio on X, ‘Started as a joke. Still laughing.’

This incident looks trivial. But I think it may be one of the most significant shifts in the Overton window on the illegal immigration issue

Pop music and Rylan were a match definitely not made in heaven, but television and Rylan were made for each other. He is a thoughtful, intelligent man and naturally amenable. He is both cosy and brainy, which makes him the natural heir to the Wogan crown. He is also not a mug, with Essex street smarts and a nose trained to sniff whiffs of windbaggery.

In the stultifyingly bland and conformist world of daytime television, now contaminated by the bien pensant opinions previously confined to the more elevated areas of programming, Rylan has always been a level above.

On yesterday’s edition of This Morning, co-host Rylan spoke calmly and thoughtfully about illegal immigration. This was portrayed as a ‘rant’, even by newspapers that might be inclined to agree with him, but it was not that. As anybody who watches Rylan would know, he is probably incapable of ranting. I will quote him at length to give you the correct impression.

He begins with a caveat.

‘This country is built on immigration. Legal immigration – a lot of the nurses, the doctors that saved my mum’s life, have come over here from other countries. They’re living a great life, they’re paying into the tax system, they’re helping this country thrive.’

So far, so ordinary. But then he continues:

‘I find it absolutely insane that all these people are risking their lives coming across the Channel. And when they get here, it does seem – and I think this is why a lot of Labour voters as well are saying there’s something wrong – it feels like, “Welcome, come on in … Here’s an iPad, here’s the NHS in the reception of your hotel, here’s three meals a day, here’s a games room in the hotel. Have a lovely time and welcome.”’

He went on, ‘There are people that have lived here all their lives that are struggling. They’re homeless. Let’s not even discuss our homeless. There are people living on the streets, veterans, all of this.’

He stressed he wasn’t simply ‘getting on a soapbox’, and acknowledged the high temperature of this particular hot potato. ‘Let me be honest, everyone’s going to have an opinion about this and you’re going to upset someone.’

Rylan Clark on illegal migration:

— Chris Rose (@ArchRose90) August 27, 2025

“there's something wrong here…here's the hotel, here's the phones, here's your iPad, here's three meals a day, have a lovely time.” Whilst Brits are “struggling, they're homeless.”

He’s right. If you disagree with him, you’re the extreme one. pic.twitter.com/W9spgH8ZPY

Indeed. The backlash was as severe as it was predictable, leading Rylan to issue a clarifying statement on X in the afternoon; ‘You can be pro-immigration and against illegal routes. You can support trans people and have the utmost respect for women. [I could give him a good argument back on that, but never mind.] You can be heterosexual and still support gay rights. The list continues. Stop with this “putting everyone in a box” exercise and maybe have conversations instead of shouting on Twitter.’

Scrolling down the replies, most are supportive, but there are some real humdingers from people who still think it’s 2017 and that they can cancel anybody at will. ‘That’s all fine,’ splutters my favourite, ‘but that doesn’t excuse you going off on an ignorant, nonsensical rant on daytime TV. I will no longer be listening to you on BBC Radio 2, and I’ll be messaging my thoughts to the directors. I urge others to do the same.’

This incident looks trivial. But I think it may be one of the most significant shifts in the Overton window on the illegal immigration issue, something that might even enter the history books. You can picture it turning up as a clip in documentaries about the 2020s. Rylan merely expressed a widely held, perfectly reasonable view that you’ll hear everywhere except on television – but now, maybe, you might. It’s impossible to think of this happening even just a few weeks ago, but the unsayable is now sayable.

There is something of the weather vane to Rylan, just as there was with Wogan. Peculiar as it might seem for such a strikingly unusual fellow, there is an Everyman quality to him. Starmer and co. should be worried. When you’ve lost Rylan, you’ve lost the country.

A fifth of MPs’ questions now ‘carded’

The House of Commons returns next week – and not a moment too soon for some in government. After a summer in which Nigel Farage has dominated the airwaves, Labour is keen to try and move the news agenda onto their preferred choice of subject. With rumours swirling about a reshuffle, No. 10 will be keen to try and promote some of the shiny new Starmtroopers elected last year. After 12 months of learning the ropes, many are keen to get their hands on a red box.

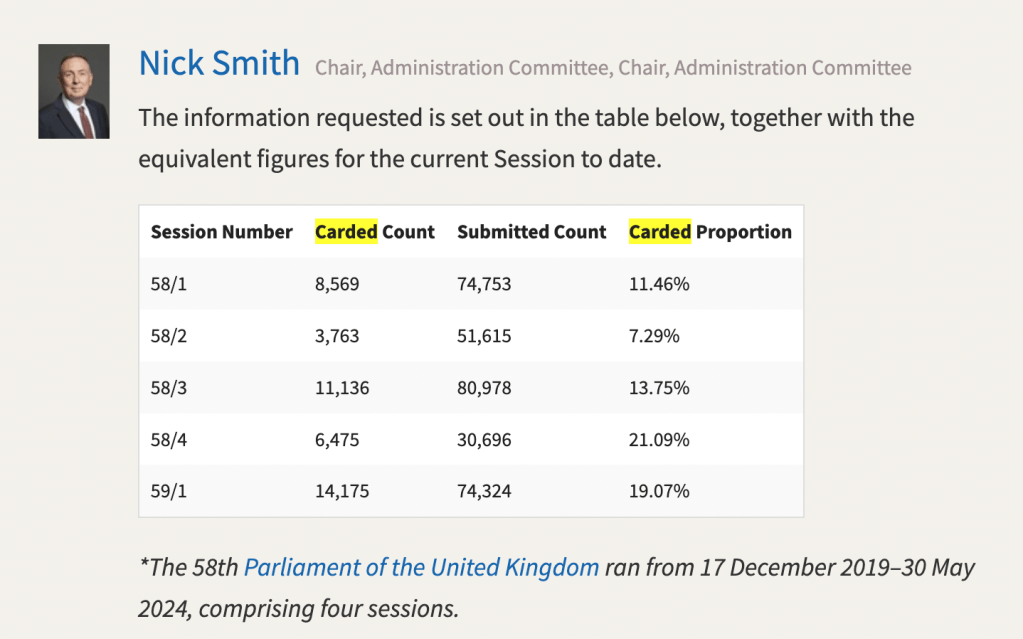

But not all in parliament are happy with how proceedings are being conducted. In recent months, Mr S has heard cross-party grumblings about the House of Commons Table Office. The men and women who work here are tasked with ensuring parliamentary questions are in shape-shape order. Yet some in the Reform and Conservative parties have questioned why so many of their submitted questions are being ‘carded’. This is the process whereby a question is returned to an MP because it is unclear or breaks procedural rules. Foul play? Or simply an excess of bad questions?

Helpfully, an answer to a parliamentary question by Kevin Hollinrake last month sheds some light on the data. One in five questions submitted thus far in this current parliament have been ‘carded’ – compared to just over in ten at the beginning of the last parliament. Perhaps poor parliamentary etiquette is to be expected when over 50 per cent of the MPs are new to the House. Hopefully, the freshers find their feet soon and the number starts to fall….

Ed Davey’s pathetic Gaza boycott