-

AAPL

213.43 (+0.29%)

-

BARC-LN

1205.7 (-1.46%)

-

NKE

94.05 (+0.39%)

-

CVX

152.67 (-1.00%)

-

CRM

230.27 (-2.34%)

-

INTC

30.5 (-0.87%)

-

DIS

100.16 (-0.67%)

-

DOW

55.79 (-0.82%)

Anti-Semitism has returned to French politics

New Caledonia is an archipelago in the South Pacific not far from Australia. James Cook discovered it in 1774, but, after concluding that too many languages were spoken there, he declined to annex it to the British Empire. France, not as cautious, made it a distant colony under Napoleon III. Today, riots are convulsing the territory. Supposedly ‘decolonial’ in aim, they are most certainly violent and fuelled by the anti-white racism that, from London to Brussels and Paris, has become the trademark of the new radical left. The strangest thing is that among the flags of the Kanak independence movement, one also sees Azeri flags. Why Azeri? Because Azerbaijan, which shares a border with Turkey and is an ally of Russia and Iran, sees an opportunity to make France pay for its support of the Armenians chased out of Nagorno-Karabakh in 2022. The dictators vs Emmanuel Macron.

As is always the case when nothing is known for sure, the air is rife with conspiracy theories concerning what happened to the helicopter carrying Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi after his visit to Azerbaijan. As when Fidel Castro denounced the ‘imperialist’ typhoons buffeting Cuba, there are those on social media who attribute the fog over the Dizmar forest, near the city of Varzaghan, to the special services of the United States, Israel, Britain and France. My Iranian friends, meanwhile, are mourning the 223 people executed by the regime since the beginning of the year. They are praying, too, for Ervin Netanel ben Tsiona, a 20-year-old Iranian Jew, who is currently sitting on death row.

I recently received a new letter of appeal from Mikheil Saakashvili, who was president of Georgia from 2004 to 2013. He’s been rotting away in a jail cell in Tbilisi as a political prisoner for the past two years. I’ve lost count of the number of letters appealing for help that he’s sent me during this time. As on each prior occasion, I recognise his feeble handwriting, increasingly shaky and nearly broken as the conditions of his detention and his state of health worsen. Solitary confinement. Hunger strikes. Successive poisonings. When Vladimir Putin invaded Georgia in 2008, Saakashvili was a sort of Volodymyr Zelensky before his time. With another invasion looming of this great but tiny nation, people are protesting at the prison gates. The number of demonstrators is twice what it was on the Maidan in Kyiv in 2014, as a proportion of the two countries’ population. I only hope Saakashvili doesn’t become the next Alexei Navalny.

I know Kharkiv very well. I filmed key scenes of three Ukrainian documentaries there. And I am spending the night on the phone with my surviving comrades who are resisting in the trenches. It’s a bitter fight, they say. The Russians are reoccupying the neighbouring villages that Zelensky’s forces had retaken in September 2022 during the Izium offensive. Kamikaze drones and Grad rockets rain down on the road leading to the Russian border and on to Belgorod. But the city is holding. The defenders’ morale is better than that of the more numerous but thoroughly unmotivated attackers. Let’s hope Ukraine’s allies keep their commitments so that this resistant, isolated nation may eventually prevail.

In France, the electoral campaign for the European parliament is entering the home straight. Compared with our neighbours, we enjoy a dubious distinction: one slate of candidates under the name of ‘Free Palestine’, whose logo features a map of the Middle East from which Israel has been erased. And another headed by neo-socialist Jean-Luc Mélenchon, that, in answer to all of the questions put to it about taxes, retirement, the cost of living, climate change, Europe’s common agricultural policy and Europe in general, has but one thing to say: ‘Israel is committing genocide in Gaza.’ That’s what the German Social Democrats of the late 19th century called socialism for imbeciles. In short, it’s anti-Semitism.

According to Time magazine, Rachel Goldberg-Polin is one of the world’s 100 most influential people. We met recently in the Jerusalem office where she battles day and night to keep the world from forgetting the hostages of 7 October, including her son, Hersh. For me, she’s first and foremost a mother, fragile and beautiful, who waits, with a heart broken but full of hope, for the return of her child. She is the best of Israel.

Letters: save our churches!

Free the C of E

Sir: Patrick Kidd’s article on the shortcomings of today’s Church of England maintains the importance of the ‘volunteers in the pews’ who bind the church together (‘Miracle workers’, 18 May). He warns that these people ‘can so easily run away’.

This is exactly what happened to the Church of Scotland in 1843 when the hierarchy got things badly wrong. The Great Disruption was caused by a disagreement over patronage: should a patron be the sole arbiter in hiring and firing ministers or did this undermine the spiritual independence of the congregation? The exit of more than 400 ministers from the Kirk’s General Assembly and the formation of the Free Church of Scotland (the Wee Frees) was the answer.

I would happily join a Free Church of England if this meant fewer bishops, more parish clergy, no Church Commissioners and all of Cranmer’s collects.

Rohaise Thomas-Everard

Dulverton, Somerset

Endangered churches

Sir: Patrick Kidd is spot on when he says that volunteers are key to the future of our churches. That’s exactly why our plan to save the country’s church buildings, Every Church Counts, makes more support for heroic volunteers a top priority.

We can’t expect the volunteers who look after these buildings day to day to be experts in historic building repairs, or in the complex task of large-scale fund raising. But we can expect dioceses and denominations to do more to support them, and to simplify the bureaucracy that makes the work harder than it should be and deters new people from getting involved.

Half the country’s most important historic buildings are churches, but many are at risk and an increasing number face closure. We need action by government, the denominations, philanthropists and local churches themselves, with local people at the heart of securing their future.

Sir Philip Rutnam

Chairman, National Churches Trust

London SW1P

Faith in politics

Sir: Douglas Murray (‘Why is it so hard to be a Christian in public life?’, 18 May) is partly right. But as a Christian, I found that neither the Conservative party, nor my constituents, made it hard. I was also encouraged to read in Katy Balls’s interview with Labour’s Shabana Mahmood (in which she stood up for Kate Forbes) that she would as a Muslim oppose loosening of the abortion law and assisted dying – views that I share, and which are almost certainly not held by the majority of her colleagues. That implies to me that the Labour party is accepting of the implications of faith in public life, as presumably it would offer the same freedom of conscience to Christians, Jews, Hindus and those of other faiths.

It seems to be mainly the Liberal Democrats and SNP who have a problem in this area, although the recent appointment of Kate Forbes as Deputy First Minister is a welcome sign of a more broad-minded approach. I pray that it lasts and that the Lib Dems follow suit. In the meantime, we can thank God that we can still worship and proclaim the Gospel freely in this country. We do not face the persecution and even murder which so many Christians and others suffer for their faith across the world and which Fiona Bruce MP speaks up against as the Prime Minister’s special envoy on religious freedom. However, there is no room for complacency. Such freedom has been hard won over the centuries in our country and is easily lost.

Jeremy Lefroy

Conservative MP for Stafford 2010-2019

Corkscrewed

Sir: Having read Sean Thomas’s article about exorbitant tipping in the USA (‘Slippery slope’, 18 May), may I suggest he does what a friend of mine does? He only tips for the food – which in fairness has to be prepared and served – but when ordering a $300 bottle of wine refuses to pay $60 for the removal of the cork. He has met some resistance but persists.

Rob Phillips

Lymington, Hants

Underground, overground

Sir: Rory Sutherland is right about how marketing transformed what we now call the London Overground (The Wiki Man, 11 May). When it was managed by British Rail, few knew of the existence of the North London line and it was actually proposed for closure in the post-Beeching era. The transfer of ownership to London Transport and its marketing as part of the Tube network transformed its profile and it is now so popular that it is sometimes difficult to get on the trains.

An interesting example of how – just as with private ownership – there can be good state organisations and bad. Also, BR was not the only one to get things wrong. The Spectator itself opposed the extension of the Jubilee line as offering poor value for money. Once again, it is so popular that it is often hard to get on the trains.

David Reed

Mirfield, West Yorkshire

Avo alternative

Sir: Mystic Martin Vander Weyer does it again, in a far-sighted reach into the future (Any other business, 18 May). I almost choked on my ‘old school’ porridge at his gag about mushy peas in the avocado analysis. Mushy peas as a super substitute? They are already here, in a nice little breakfast venue in Piccadilly, hiding in plain sight and labelled ‘No Avo on sourdough’ (naturally). The ‘No Avo’ is mashed or pressed peas with some watercress, chilled. It was pleasant enough, while others might resurrect an old City label which Martin will remember: ‘Cannot recommend a purchase.’

W. McCall

Kippen, Stirlingshire

Holy wine

Sir: Domaine de la Vieille Eglise is not, pace Jonathan Ray (Wine club, 11 May), France’s only working winery in a church. The Cellier des Dominicains inside a Dominican convent built in 1290 in Collioure, Roussillon, is a flourishing cooperative.

Christopher McKane

North London

Big island

Sir: Toby Young refers to Britain as ‘a small island in the North Sea’ (No sacred cows, 18 May). Britain is actually a large island, the ninth largest in the world, far larger than such sizeable ones as Iceland, Cuba, Sicily and Corsica. If you want a small island, think of one of the Greek Cyclades or the Inner Hebrides. Toby may well have meant ‘a small country’, but even that description probably needs qualifying.

Stephen Terry

Lustleigh, Devon

Dead cat strategy

Sir: Toby Young’s article on accidentally abducting cats reminded me of a friend whose cat died days before he was due to exchange contracts on a new house. His wife insisted he bury the cat in the ‘new’ garden which they did not yet own. So my pal crept out at 2 a.m., slipped into the garden and buried the cat. The sale fell through two days later.

Peter Fineman

Barrow Street, Wiltshire

The real reason Ofcom has gone after GB News

I don’t envy the people who run Ofcom. On the one hand, they’re under enormous political pressure to sanction GB News, which, in the eyes of its establishment critics, is a contaminated river of far-right propaganda that’s polluting the ‘delicate and important broadcast ecology of this country’ (Adam Boulton). But on the other, they want to preserve their status as the keepers of the ring and cannot be seen to be holding GB News to a higher standard than other broadcasters. That makes their lives complicated because, in reality, the channel’s politics are far closer to the Telegraph than they are to Fox News, and it’s no more partisan than LBC or Channel 4 News. Indeed, it may actually be less politically biased than those broadcasters, with a recent poll discovering that more GB News viewers intend to vote Labour than Conservative.

Ofcom has enormous latitude when it comes to applying these rules

Until now, Ofcom’s solution to this dilemma has been a typical English fudge in which the regulator appears to take the complaints of left-wing activists about the channel seriously, dutifully ‘investigating’ them over several months, only to conclude that it hasn’t actually breached the Broadcasting Code or – if it has – in such a minor way that it’s only deserving of a wrist-slap. But that changed this week with the announcement that Ofcom is considering whether to impose a ‘statutory sanction’ on GB News, having concluded that People’s Forum: The Prime Minister,in which Rishi Sunak was grilled by a studio audience last February, broke ‘due impartiality’ rules. If it does decide to wheel out the big guns, the channel’s punishment could be anything from a fine to the removal of its broadcast licence.

Why the harsher treatment? Ofcom says it’s because this is the third time the channel has breached ‘due impartiality’ rules, that the rules in question are important (they require broadcasters to give due weight to a wide range of significant views when it comes to matters of major political controversy) and it’s incumbent upon GB News to follow these rules at the moment because we’re in a ‘period preceding a UK general election’. But having looked in detail at the regulator’s case, it’s difficult to avoid the conclusion that the real reason it’s taken the gloves off is because it knows which way the wind is blowing.

Take the last part of Ofcom’s rationale. You could say we’re in a period preceding an election at more or less any time, given that the Fixed Term Parliament Act has been repealed and the Prime Minister can call an election whenever he wants. To argue that broadcasters should have particular regard for ‘due impartiality’ during an actual general election campaign is one thing, but Ofcom is introducing an entirely novel concept to justify its decision.

What about the charge that the programme in question failed to give due weight to a wide range of significant views? GB News had a field day on Monday, pumping out clips of the Prime Minister being hauled over the coals by a studio full of undecided voters. He was skewered on the government’s ‘chronic underfunding’ of social care; the likely failure of its Rwanda policy; the housing shortage; its lack of support for the LGBT community; and its neglect of the vaccine injured. Aha, says Ofcom. But the audience members weren’t given an opportunity to ask follow-up questions, so Sunak ‘had a mostly uncontested platform to promote the policies and performance of his government’.

Having watched the programme, I wouldn’t describe the response to the Prime Minister as ‘uncontested’. Yes, the questioners didn’t get a right of reply, but no sooner had Sunak fielded one fast bowl than another was coming straight for him. The claim that this is a third offence, with the channel having been found guilty twice before of breaching the same rules, might carry more weight if those other offences were serious. But they weren’t, which is why they attracted no penalties. It’s a bit like a magistrate saying to a defendant that because he’s been caught going 23mph in a 20mph zone twice before, he’s now considering sending him to jail for doing so a third time.

The truth is, Ofcom has enormous latitude when it comes to applying these rules, which is why it hasn’t sanctioned LBC for its almost identical Call Keir show. How its executives interpret the ‘due impartiality’ requirements is at their discretion, which means their decisions are unavoidably political. Indeed, this latest ruling is a regulatory version of lawfare – a thinly disguised political attack. Ultimately, it will do more damage to the reputation of Ofcom than GB News.

The Battle for Britain | 25 May 2024

Harris Tweed, the miracle fabric

To understand the development of technology, you may be better off studying evolutionary biology rather than, say, computer science. A grasp of evolutionary theory, with the facility for reasoning backwards which it brings, is a better model for understanding the haphazard nature of progress than any attempt to explain the world by assuming conscious and deliberate intent.

One useful concept from evolutionary thinking is the idea of the ‘adjacent possible’. As the science writer Olivia Judson explains: ‘Evolution by natural selection only works if each mutational step itself is advantageous. There’s no such thing as advantageous in a general sense. It’s advantageous in the circumstances you’re living in.’ In the field of product design, there is an analogous idea known as ‘Maya’, a phrase coined by Raymond Loewy, which stands for ‘Most advanced yet acceptable’. Any successful product should be notice-ably better than those which precede it, but not so different as to be alarming, incomprehensible or unbelievable. The plug-in hybrid electric car might be a good example of a Maya product, in that it introduces the benefits of electric propulsion without the fear fully electric vehicles often induce.

Any successful product should be noticeably better than what went before, but not so different as to be alarming

What is fascinating about this process is how uncertain it has become. Apple, one of the world’s wealthiest companies, has spent billions developing the Vision Pro, a clever set of goggles which has the potential to change computing, but which also has the potential to sell in tiny numbers and end up in a cupboard after a few months of novelty. No one yet knows.

Many government programmes fail because they don’t understand Maya or the adjacent possible. For instance, government grants are available for installing heat pumps, but only if you make a dramatic and expensive one-off transition: you must rip out your gas boiler, which has given you dependable service for 20 years, and trust your home heating to something entirely new. Evolution doesn’t make gambles like that – and neither do people.

There are also intertwined dependencies in evolutionary progress. One adaptation must establish itself before another can take root. Sometimes two things combine to great effect. The invention of the Penny Post in the UK was obviously dependent on the growth of the railways – but to some extent the development of the railways also required the introduction of the Penny Post. That’s because you can’t just travel across the country and turn up at someone’s door announcing you are staying for a week: you need an inexpensive form of communication to make arrangements first.

Hence some good ideas fail at the first attempt but succeed later. I always thought Google Glass was a fundamentally good idea: at the time it was advanced but not yet acceptable. Interestingly, with recent advances in artificial intelligence, Google has just announced it plans to relaunch a spectacle–style device.

But the really peculiar characteristic common to both processes is how uneven the pace of progress seems to be. Some things change repeatedly and rapidly, other things seem stuck. Email has scarcely improved in 15 years. Our practice of constructing houses would be recognisable to a Roman builder. At the same time, we are often blind to the genius of things that have been around for ages. I have a theory that if Harris Tweed had been invented by scientists in California last year we would hail it as a miracle fabric. Breathable, largely waterproof and warm, you can throw dirt at it and pack it in a suitcase for six months, and with a brush and a shake it’s ready to wear. Some things are unimprovable. Sharks have been around for longer than there have been trees. J.K. Starley developed the Rover Safety Bicycle in 1885. Every bicycle since has followed the same design.

Dear Mary: how do I stop our cousins’ dog peeing on the curtains?

Q. I have a friend whom I see quite often who keeps asking me if I will ‘get her invited’ for a weekend to the beautiful and luxurious country house of another friend. The country-house host is a long-standing friend and she barely knows the friend who wants to be invited. I wouldn’t dream of suggesting they invite her but am under constant pressure to do so. I am very fond of this first friend but am really embarrassed that she cannot see how pushy she is being and I don’t know how to get her to stop going on about this. What should I do?

– F.G., Bath

A. Next time the pushy friend chivvies you, put the ball into her own court. Say: ‘I am sure she would love to have you. You just need to gee her up a bit and let her get to know you. Why don’t you ask her to lunch or the opera or something? Then she’s sure to remember to ask you.’

Q. To be blunt, our elder daughter’s godfather is as rich as Croesus. (He and my husband were at university together.) Our friend is always coming to stay and saying: ‘Sorry I’m an absolutely hopeless godfather. I haven’t brought anything,’ and the temptation is to reply: ‘Yes you are hopeless, you have literally never given her a present.’ Mary, can you think of anything subtle that could be said or done? He is unmarried, so has no wife to nag him. By the way, we like him very much.

– Name and address withheld

A. Next time he mentions that he is a hopeless godfather, reply that your husband would be too if he had to remember Christmas and birthdays. Add: ‘Instead he has taken the practical step of instructing his lawyers to accommodate his godchildren in his will. So he never needs to worry.’ This may prompt your Croesus-rich friend to do the same.

Q. Next month some older and slightly eccentric cousins, whom we love, will be making their annual three-day trip down south to stay with us for Ascot because we live only 12 miles from the racecourse. Our problem, which we are hoping you can help us with, is that they bring their male lurcher, which without fail cocks its leg on our hall curtains every time he comes in or out of the house. For some reason they deny it point-blank.

– H.S., Maidenhead

A. Be doubly pleasant to your guests, but prepare for their visit by dropping each of the hall curtains into a black plastic refuse sack, bulldog-clipped to half way up the curtain. In this way they can still be opened and shut but are out of range of the ‘jet stream’. If the cousins query the bags’ presence, smile and change the subject.

The best bottle to come from the Gigondas

One needs wine more than ever, yet when imbibing, it can be hard to concentrate. So much is going on. We were at table and the news came through about Slovakia. Was this an obscure incident, regrettable but below the level of geopolitics? Or would it become a second Sarajevo? Fortunately, that seems unlikely. In Mitteleuropa, there are always ancestral voices prophesying war and there is usually plenty of dry timber. But it does not seem that this assassination attempt will be the spark.

The Barruols have a reputation for delightful eccentricity but they are committed to their bottles

When we had come to that conclusion, there was an obvious next step. Gavrilo Princip nearly missed his chance to murder the Archduke. If he had failed to do so, would there still have been a war? We decided that the answer was yes. The central powers were squaring up and the public mood resembled that of a war horse pawing the ground and waiting for the sound of trumpets. Winston Churchill did warn that the wars of peoples would be more terrible than the wars of kings but even he did not realise what everyone was letting themselves in for. The bands struck up, the flags flew, the joyous troops set off – to chew barbed wire in Flanders, during the second fall of man.

One hundred and ten years later, the damnosa hereditas of 1914 is still with us. The fall of empires always leads to carnage. In 1914, the precarious state of Europe led to war and chaos. The precariousness persists and shows no sign of being resolved.

So pass the wine. We were drinking various bottles of Gigondas from the house of Barruol. Louis is the current maître but the family have been there for 500 years. They call their wines Saint Cosme, as in Cosmas and Damian. The Barruols have a reputation for delightful eccentricity yet they are committed to their bottles. Their range stretches from Côte du Rhone upwards to Château Saint Cosme and Côte Rôtie. They are all good value and I do not believe that a better wine comes out of Gigondas. Berry Bros are their agents in London, which is not surprising. They have been in the business for almost as long as Saint Cosme and they know excellence when they taste it.

Apropos excellence, sadness does not only arise from politics and statecraft. Admittedly, Tony O’Reilly, who has just died, had not been well – and he was 88. But he was a broth of a boy and earned a magnificent send-off, as befits one of the most remarkable men to emerge from modern Ireland. He burst into fame as a rugger player for both Ireland and the British Lions. Still in his teens as an international, he was a Prince Rupert of a winger who could bring crowds roaring to their feet. Whenever he had the ball, there was the possibility of a try.

He then became an equally dashing businessman which led him to philanthropy and the ownership of newspapers. Above all, he played a crucial role in modernising Ireland. In the decades after the travails and bloodshed before Eire broke away, Éamon de Valera led the infant nation into a sterile and backward theocracy. Matters would have been very different if Michael Collins had not been assassinated; the wrong fellow was shot.

From the 1950s, everything started to change and Tony was part of that process. A proud Irishman, he was equally at ease in London and New York. By 1960, it appeared as if a new Ireland was coming into being, with him as one of its leaders and as befits a member of an Irish side which included Prods and Papists, Tony did not have a sectarian atom in his anatomy.

I saw a bit of him when he owned the Independent. I do not remember what we drank, but no one went thirsty. He loved talking politics, culture, rugby and the human condition. Larger than life, he was a life–enhancer. We will cherish his memory.

The myth of the global majority

‘You make the cotton easy to pick, Mame,’ sang my husband with execrable delivery. ‘No,’ I said, ‘You can’t sing things like that now. In any case, I was talking of Bame, not Mame.’

The hit musical from 1966, starring Angela Lansbury, has only the most tangential relevance to the latest lurch in approved terminology for what we were encouraged to call Black and Minority Ethnic people until that term was expelled from polite conversation. Now the trendy label is global majority. ‘The term Global Majority was coined as a result of my work in London on leadership preparation within the school sector between 2003 and 2011,’ says someone called Rosemary Campbell-Stephens. In a biographical note in her paper ‘Global Majority; Decolonising the Language and Reframing the Conversation about Race’, she says ‘her great love is speaking, whether as a keynote, in podcasts or dialogue about equity or decolonisation’.

The Oxford English Dictionary, however, cites examples of global majority from 1971 onwards, though it notes that in early use it was not a ‘fixed collocation’.

I find the concept of a majority undefined by any common feature rather hard to grapple with. If you started with the Ainu, an ethnic group indigenous to Japan, then everyone else is the global majority, including poor white folk. Quite a lot of people are Africans, but the global majority aren’t. The same goes for people of Chinese heritage.

There used to be a way of referring to the dead as the majority. ‘This Mirabeau’s work then is done,’ wrote Thomas Carlyle. ‘He has gone over to the majority.’ Sometimes they were called the silent majority, a phrase more often used of those who, unlike the vocal minority, find their great love in something other than speaking. I remember being told that more people are alive today than had ever lived before, but that is not true. If there are eight billion or so people alive today, more than 12 times as many have died.

Portrait of the Week: Infected blood apologies, falling inflation and XL bully attacks

Home

Rishi Sunak, the Prime Minister, said: ‘I want to make a wholehearted and unequivocal apology’ for a ‘decades-long moral failure at the heart of our national life’, as described in the report by Sir Brian Langstaff from the Infected Blood Inquiry, which found that successive governments and the NHS had let patients catch HIV and hepatitis. Sir Keir Starmer, the Labour leader, apologised too. So far more than 3,000 have died, of the 30,000 infected with HIV or hepatitis C from blood products or transfusions between 1970 and the early 1990s. Interim compensation of £210,000 will be paid to some within 90 days. BT postponed until January 2027 a deadline for forcing customers to switch from copper-based landlines to internet-based services.

Wylfa on Anglesey was earmarked for a new nuclear power station. The High Court ruled as unlawful legislation amended by statutory instrument that had attempted to increase police powers against demonstrators by lowering the threshold for what counted as ‘serious disruption’. After people fell ill with diarrhoea caused by Cryptosporidium parasites, 16,000 households in Brixham, Devon, were told by South West Water to boil drinking water. Water companies in England and Wales want bills to increase by between 24 per cent and 91 per cent in the next five years, according to the Consumer Council for Water. Manchester City became the Premier League champions for the fourth time running, pipping Arsenal to the title. A woman in Hornchurch, Essex, died after being attacked by her two registered XL bully dogs.

Annual inflation fell to 2.3 per cent in April from 3.2 per cent in March. Labour issued a card with six pledges: economic stability, the establishment of Great British Energy, a publicly owned clean energy company, cutting NHS waiting lists, stopping the gangs arranging small boat crossings, providing more neighbourhood police officers and recruiting 6,500 teachers. In the week ending 20 May, 324 migrants arrived in England in small boats. The online used-car site Cazoo went into administration. Sir Anthony O’Reilly, the rugby international, creator of Kerrygold butter, newspaper owner and bankrupt, died aged 88. Frank Ifield, who topped the charts in 1962 with ‘I Remember You’, died aged 86.

Abroad

Karim Khan, the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, sought arrest warrants for Benjamin Netanyahu, the Prime Minister of Israel, Yoav Gallant, the Israeli defence minister, Ismail Haniyeh,the political leader of Hamas, Mohammed Deif, the group’s military chief, and the leader of Hamas in Gaza, Yahya Sinwar, over alleged war crimes in the Gaza conflict. President Joe Biden of the United States said: ‘The ICC prosecutor’s application for arrest warrants against Israeli leaders is outrageous.’ He said there was ‘no equivalence – none – between Israel and Hamas’. Ireland, Norway and Spain said they would recognise a Palestinian state from May. Ebrahim Raisi, the President of Iran, died in a helicopter crash, along with Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, the Foreign Minister, in a mountainous region near the border of Azerbaijan, where they had been meeting President Ilham Aliyev.

Russia used hundreds of glide bombs against Ukrainian settlements. Thousands were displaced by a Russian advance near Kharkiv. Ukraine said that a missile attack had destroyed a Russian minesweeper, the Kovrovets, in occupied Crimea. President Vladimir Putin of Russia visited Beijing for talks with Xi Jinping, the ruler of China. Robert Fico, the Slovak Prime Minister elected last year after opposing military support for Ukraine, was reported to be no longer in danger of losing his life four days after being shot four times by a man who was arrested.

Australia and New Zealand sent planes to New Caledonia to evacuate citizens caught by unrest over elections; President Emmanuel Macron of France flew in to sort things out. A court in Greece abandoned the trial of nine Egyptian men accused of causing a migrant shipwreck in the Mediterranean in which 600 were feared drowned, because the judges ruled they did not have jurisdiction, since the vessel sank in international waters. The ship that smashed into a bridge in Baltimore on 26 March was towed to a marine terminal; the crew of 21 remained aboard. Spain withdrew its ambassador to Buenos Aires after President Javier Milei of Argentina visited Madrid and said of the Spanish Prime Minister: ‘When you have a corrupt wife, let’s say, it gets dirty.’ Naples was hit by 160 earthquakes in one night. A British man aged 73 died on a Singapore Airlines flight from London, diverted to Bangkok, which was hit by turbulence. CSH

A summer election is suicide for the Tories

As soon as Rishi Sunak told the House of Commons that ‘there is going to be a general election in the second half of this year’, nervous Tory MPs spotted a problem: that could mean 4 July, which the Prime Minister has now announced will be the election date.

Calling an early election is an admission of defeat – and that, on everything from public finances to public services, the worst is yet to come

With every opinion poll pointing to a Labour landslide, it’s unclear what Sunak is trying to gain – unless he has given up hope of victory altogether. Calling an early election is an admission of defeat and signals that, on everything from public finances to public services, the worst is yet to come.

Of course, holding the line until November would have been tricky. The Tory party is in demonstrable disarray. Every week there have been rumours either of a new defection to Labour or a freshly brewed scandal. Some Tory MPs can’t even wait a few months for this political torture to end, and are already taking new jobs. Displays of sleaze and selfishness serve to throw more mud on the Conservatives’ reputation. Sunak’s approval rating, meanwhile, is lower than that of almost any prime minister since records began.

Many Conservative MPs think that the choice of the next election is between a defeat that is survivable (that is to say, the party keeps about 200 MPs out of the current 344) and one that could be an extinction-level event (keeping just close to 50 MPs). Gallows humour is the main force sustaining the Tory tea rooms, with more seasoned campaigners quoting Tennyson (‘Into the valley of death rode the six hundred’) and would-be Tory opposition leaders openly canvassing support.

When Sunak became Prime Minister, he had hoped that the Tories would, by now, have narrowed the opinion poll gap to about ten percentage points – at which stage the race would be (as he put it) ‘contestable’. He had hoped that his presence in No. 10 would lower UK borrowing costs: this was not to be. He had hoped NHS waiting lists would be falling quickly by now: this has not happened either. He had hoped Labour would self-immolate, but Keir Starmer has proved to be resilient.

So why, then, should he have waited for a November election? Because there are, even now, credible grounds for believing that things will seem better by then. Net migration is due to start falling quickly when the tighter visa regime kicks in – with the number of visas for study and skills down 25 per cent year-on-year. But this will only become clear when the figures are collated in the autumn. The obvious story at the moment is of a party that ‘took back control’ of the borders via Brexit – only to promptly lose control of them again.

The NHS waiting list – 7.5 million at the last count – is expected to fall below six million by the end of this year and to a ten-year low by the end of next year. But again, this success – the result of extra NHS capacity – will only be apparent in the autumn as the effect of the junior doctors’ strikes will take time to unwind. A summer election means that the official line on the NHS appears to be one of unmitigated failure.

Then we have the cost of living. With inflation fast heading back to the 2 per cent target, the average salary is rising more quickly than the CPI index. This means that the long contraction in living standards is finally over – and the prediction is that they will steadily rise over the next four years at least. But none of this is, to put it mildly, evident at present. It wouldn’t have been much more so in a November general election, but at least there would have been some positive data to point towards.

How much do people trust the Conservative party now, after the mayhem of the last few years and with the largest tax burden in living memory?

The Prime Minister may yet succeed in deporting failed asylum seekers to Rwanda – stranger things have happened – but that won’t come to fruition for several weeks. To call an election now means Sunak looks like he’s failed to deliver on his promise to ‘stop the boats’: there have been more arrivals so far this year than in any other. Even if he does manage to outwit the campaigners and send a flight to Rwanda, any effect on refugee numbers will take months to be noticeable. The Labour party will have no shortage of sticks with which to beat him.

There could be a deeper problem for Sunak: the country has stopped listening to the Tories. This happened to John Major, who engineered a strong and long-lasting economic revival, only to find that it was, as he put it, a ‘voteless recovery’. Perhaps the biggest question when the general election comes will be: how much do people trust the Conservatives after the mayhem of the last few years – and with the largest tax burden in living memory?

Sunak has positioned himself as a results-based Prime Minister: more perspiration than inspiration, perhaps, but someone who can nonetheless be relied on to get things done. As he put it when he released his five pledges: ‘We’re either delivering for you or we’re not.’ To call a summer election before he has anything to substantiate any claim of having ‘delivered’ on his promises is an admission of defeat.

Inside Labour’s fight with the unions

By the end of the year, Britain may be one of the few countries in the democratic world where the right is losing. In America, Donald Trump is the favourite to win. Ahead of next month’s European Parliament elections, momentum is with Germany’s AfD, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally and Austria’s Freedom party. Migration is the most pertinent issue pushing Europe rightwards, but many voters are also turning to insurgent right-wing parties as a rebellion against the cost of net-zero policies.

Labour sees an electoral benefit in sticking to its green energy plans to stop voters defecting to the Greens

In the UK, the future of green scepticism looks somewhat different. Should Starmer win a majority, the fiercest critics of his green ambitions won’t come from the opposition, but from his own side: the unions.

Unite, the trade union that gives more money to Labour than anyone or anything else, launched a campaign this week complete with banners, billboards and newspaper wraparounds. Its goal isn’t to preserve a Labour pledge, but to get one to be scrapped: Ed Miliband’s plan to block new oil and gas licences in the North Sea.

Gary Smith, the head of the GMB trade union, has ridiculed the shadow energy secretary’s agenda, saying that the only ‘green jobs’ for British workers involve either lobbying in London or counting the dead birds under wind turbines. Now Unite has a similar message. The campaign slogan is ‘No ban without a plan’. Any restriction on oil and gas exploration would badly affect industrial jobs – disproportionately in the north-east. In what way is Labour’s plan anything other than a green version of the Thatcher-era closure of the coal mines and steelworks? It’s a question the party has to answer.

‘Labour needs to pull back from this irresponsible policy,’ says Sharon Graham, Unite’s general secretary. ‘There is clearly no viable plan for the replacement of North Sea jobs or energy security.’

A study this week from Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen gave credence to Unite’s concerns. It warned that the UK is running out of options for a ‘just transition’ for oil and gas workers to equally good jobs in renewables. ‘Bottom line: the percentage of workers who will get a decent job is less than half a per cent,’ says one trade unionist.

So the unions are fighting for their members, even if that means fighting Labour. Unite’s six-week campaign is focused on Scotland and six constituencies believed to be so closely contested that Labour’s green agenda could cost the party those seats at a general election. Scottish Labour, fearing a voter backlash, has long been uncomfortable with Miliband’s green crusade. Anas Sarwar, the party’s leader in Holyrood, has said ‘oil and gas will play a major part of the energy sector for decades to come’.

At the GMB, Smith calls Miliband’s oil policy ‘bad for investment, jobs and national security’. As one Labour union insider puts it: ‘Smith is straightforward “drill-baby-drill”. Unite’s position is there has to be net zero – but not if Scottish workers are sacrificed on the altar.’

What Smith and Graham have in common is that they are a new breed of union leader. When Len McCluskey ran Unite, he was an ideological Corbynista who wanted control over Labour’s party mechanisms – and even influence over the selection of Labour candidates. ‘Sharon is the political opposite of McCluskey,’ says a union figure. ‘She’s led a turn away from parliamentary gazing to the shop floor.’

Within the shadow cabinet, there is a confidence that Unite – which really wants investment – will come around and see that some of its demands have already been met. A Labour source emphasised that Unite isn’t really asking to change the licences policy, but for greater support: ‘It is campaigning for things we’ve agreed to.’

In the meantime, Unite has played its favourite trick of withdrawing funding: some £6 million is said to have been diverted from Starmer’s war chest. However, since Labour now takes much more from private donors, this is not quite the slam dunk that it would have been a few years ago. ‘Relations between Keir and Sharon are frosty,’ says a party figure. ‘But he also needs her less.’

The debate over oil and gas is just one of the green policy challenges that a Labour government will face in its first term. Starmer has already axed his plan to spend £28 billion a year on green investment, which had hitherto been his signature economic policy. While there was little in the way of a Labour rebellion when the U-turn was announced, some MPs wonder privately whether Miliband will be able to deliver his pledge of clean power by 2030. Even his biggest supporters won’t deny that the target is incredibly ambitious. In shadow cabinet, parallels are being drawn with the vaccine task force set up during the pandemic. It is seen as an example of what can be done when government and industry have clear priorities: they can deliver extraordinary results.

Some party figures are most concerned about the role planning reform will have to play in making the green agenda work. They worry about the community kickback to the number of pylons and amount of above-ground infrastructure that will be needed. The plan is to encourage community consent by giving households near to new infrastructure money off their energy bills.

Despite these concerns, Labour sees an electoral benefit in sticking to its green energy plans, because the policies will stop voters from defecting to the Green party. Labour strategists have long believed that sending out Miliband with his ukulele to sing about the pros of wind turbines is a good way to keep the coalition on side.

But as the financial pain caused by net zero becomes more obvious, the fight between Labour’s green idealists and the protectionist unions will only get worse. A green plan that leads to mass unemployment among industrial workers is one that the party’s oldest paymasters will not be able to get behind.

The deluge: Rishi Sunak’s election gamble

‘Only a Conservative government, led by me, will not put our hard-earned economic stability at risk,’ said Rishi Sunak as he announced a general election on the steps of Downing Street in the pouring rain. Upon these words, the Labour anthem ‘Things Can Only Get Better’ boomed out from the street. The din made the rest of his speech nearly inaudible. His suit jacket went from wet to soaking. ‘It’s bizarre,’ said one former minister. ‘How are we supposed to trust No. 10’s judgment when no one in the group even knows what an umbrella is?’

Sunak’s gamble is that while he can’t get a hearing in government, he might get one in a short election campaign

A few hours earlier, almost no one in the cabinet had any inkling that the Prime Minister was about to lead them into battle. They had dismissed the rumours of a summer election as wild speculation.

‘To go now would be a death wish,’ said one cabinet minister yesterday morning. ‘I quite like my job and don’t want to end it.’ Yes, the cabinet meeting had been moved from Tuesday to Wednesday, but Sunak had been travelling so his schedule was off kilter. The election speculation was chalked up as crossed wires. The last prime minister to spring an election on the cabinet with no prior discussion was Theresa May. That did not end well. Would Sunak really tempt fate like this?

But for weeks the Prime Minister has held the view that an election campaign should be launched as soon as enough decent economic news comes through. First, it turned out the UK economy grew faster than expected at the start of the year. Next, inflation fell. Those pieces of news were enough, he thought, to make his pitch: that he has a plan – and Labour doesn’t.

There were dissenting voices around the cabinet table. Esther McVey, who Sunak calls his ‘minister for common sense’, said voters may not feel enough economic improvement at this stage to swing the vote, but they might if an election was held in November. Several others in the cabinet agreed, although none said so at the time. ‘Going now doesn’t make sense,’ one said before yesterday’s meeting. ‘We will have more to point to on the economy and migration by the autumn.’ Chris Heaton-Harris – the Northern Ireland Secretary – also voiced concerns. But he’s standing down at the election and said he’d support the Prime Minister’s decision.

Sunak came to the view that there is little evidence so far to suggest that waiting for better economic weather would lead to greater Tory support. After ten months of real-terms wage increases, for example, the polls have barely moved. As John Major found in 1997, economic recoveries don’t always translate into political ones.

The hope in CCHQ and Downing Street is that calling an election now will focus minds and mean the Tories are at least heard. ‘A lot of voters are currently not listening,’ says a minister. The thinking is that, with an election, voters – especially those who are usually politically minded – will sit up and pay attention. ‘Now is the time for the country to look at the actual choice they have,’ says a senior government figure. Sunak’s gamble is that while he can’t get a hearing in government, he might get one in a short election campaign.

The Tories will fight the election on the economy and the idea that Sunak brought stability to the country. The second part of the campaign will be to position him as a leader willing to hold unpopular positions when he believes they are right (such as on Covid lockdowns, welfare reform and the need to moderate net zero). At yesterday’s cabinet meeting, Sunak’s close ally and protégé Claire Coutinho opted not to complain about the election and instead praised her boss as a man unafraid to stand up for what he believes in. Starmer will be attacked as a weathervane, who holds whatever position suits him that day.

Victory may look unlikely but, as the last ten years of elections have often showed, polls can be wrong and experts can be confounded. That said, few in Sunak’s party believe his timing is anything other than an attempt to lose less badly. Isaac Levido, the Tory election strategist, has previously been of the view that waiting until autumn is the best option. Others, such as the deputy prime minister Oliver Dowden and James Forsyth, formerly of this parish, are said to have seen the merits of going sooner. However, the final decision was ultimately Sunak’s. His circle has been divided: on current polls, most Tory MPs will not be returning to their jobs. Those with the safest seats have been the ones most likely to say that holding an election when the party is 20 points behind in the polls is worth the risk.

For some Tory MPs, the election call was so inexplicable they refused to believe it at first. An hour before Sunak’s announcement, when a July poll was being reported as fact, some were walking around parliament insisting it could not be the case. The optics of the campaign launch was not terribly auspicious. The protestors were on song and the rain had been falling long before the lectern was positioned in front of No. 10. ‘It’s all too much of a metaphor,’ said one MP.

And what about the tax cuts Jeremy Hunt was promising? He had spoken of another ‘fiscal event’ before the election, but it was never clear how his giveaways would be paid for. Then there are potentially unpleasant surprises: increases in the NHS waiting list when the number is supposed to be falling, for example. More embarrassing immigration figures. Or perhaps the prospect of summer riots in prisons or coming HGV licence changes that could mean lorries crossing into Europe are held up in endless queues.

No prime minister has ever called an election from 20 points behind and won. One cabinet member said just before the election was called that a good result would be retaining 200 MPs (implying a landslide Labour majority) and a bad result would be keeping just 50-odd. ‘Our best message in this campaign is saying that we’re going to lose, but Labour doesn’t deserve a crushing majority,’ said another cabinet member. ‘But we can’t say so. We have to pretend that we stand a chance of winning.’

CCHQ has a few lines of varying plausibility to raise morale among MPs. One is to point to the national polling share in the recent local elections, which was closer to a ten-point Labour lead than the 20 points suggested in general election polling. But many Tory MPs believe those results were dire and hardly constitute a launch pad from which to take the decision to the country. ‘I don’t know what they are thinking,’ says a concerned MP, ‘other than maybe they want it all done now.’ Nadine Dorries, the Boris Johnson loyalist who quit in protest at Sunak’s refusal to ennoble her, claimed that Sunak wants to go early because the Californian school term starts in August.

On the right of the party, some MPs are pleased because they believe the failure of the supposedly ‘wet’ Sunak would pave the way for someone more radical in opposition. But it’s not clear who that candidate would be. Kemi Badenoch remains the bookmakers’ favourite and the shadow Tory leadership election will be a subplot throughout the upcoming campaign.

All of this is seen by Labour as richly comic. Shadow ministers were truly taken by surprise at Sunak’s decision and the party’s strategists had been reluctantly coming round to the likelihood of an autumn election. But Starmer had his election speech ready and rehearsed. Morgan McSweeney, his main lieutenant, has long believed that an election before the autumn was probable. Labour’s manifesto is nearly complete, and many policy announcements are ready to go. The final document should be thin and simple: Starmer wants to get away with saying as little as he can, to present as small a target as possible.

Might the Tories have some ammunition by 4 July? There are still some who claim a Rwanda flight mid-campaign is possible, ideally with enough time to also demonstrate a deterrent effect. However, this seems unlikely. Instead, part of the reasoning behind going earlier than planned was concern that lawyers would bring system legal challenges that could tie it all up.

Sunak is taking the classic underdog approach to debates: to say ‘yes’ to everything and try to portray Starmer as a shyster on the run should (as the Tories expect) he try to limit his appearances to just two or three debates.

‘How are we supposed to trust No. 10’s judgment when no one in the group even knows what an umbrella is?’

The Tories want to have a special broadcast focus on GB News. In the words of one campaign figure: ‘It is the most important election channel.’ The reason for this is its viewership among the coalition of Tory voters that Johnson assembled in 2019. BoJo himself will be asked to join the campaign trail to woo these voters back. David Cameron, whose return to government seems destined to be short-lived, will be deployed in the Lib Dem-facing seats.

In Scotland, the SNP is facing a massacre as John Swinney, its caretaker leader, is plunged into battle after just a few weeks as First Minister. Labour is hoping to take about 20 seats from the SNP and the Tories about five, but the result should mean that Swinney stands aside after the campaign and Kate Forbes, his deputy, picks up the pieces.

Perhaps the biggest single Tory hope is that Reform may implode or, at least, never get the chance to develop into a genuinely national political party. As an opinion poll option, Reform is the preference of about 12 per cent of the public. But it has few candidates, no national apparatus, no get-out-and-vote operation. If it fails to present itself as an electoral force, then at least some of its voters will be up for grabs. Just as the contraction of Nigel Farage’s Ukip vote in 2015 took Cameron over the line for a majority, the Tories would be the beneficiaries should Richard Tice’s party seem more irrelevant in a general election than in the locals.

This is, perhaps, the Tories’ best chance for a miracle. ‘When you look at the polls, Reform and the Tories are backed by about half of the country,’ says one of the more optimistic cabinet members. ‘We think the same things as the country think, and Labour doesn’t really think anything. The argument should not be too hard to win.’ The worry, though, is that Farage springs a political comeback in the coming days.

Anyone who does think the Tories will win should, of course, go to the bookmakers, who are offering odds of 25-to-one on a Tory majority. It’s hard to think of a Conservative government that has faced more daunting odds. ‘We could win: stranger things have happened,’ says one former leadership contender. ‘It’s just that I can’t think of any.’ Yet for all their doubts over Sunak’s strategy, Tory MPs have little option but to back him and hope for the best.

Get more election analysis on Spectator TV:

The unstoppable rise of country music

When a major artist releases a new album, the first thing to follow is the onslaught of think pieces. And when Beyoncé released Cowboy Carter earlier this year, the tone of these think pieces – especially on this side of the Atlantic – was one of slightly baffled congratulation. Here, at last, was a pioneer who might drag this hidebound genre – of sequins and satin, of lachrymose, middle-aged songs about drink and divorce – into the modern age.

‘Modern country is like punk for the Hannah Montana generation’

The only problem is that Beyoncé was not leading; she was following. Beyoncé pivoted to country not to make it cool, but because it’s become cool – and more of a commercial powerhouse than it has been for years. In the US, just 23 country songs have topped both the country chart and the Billboard Hot 100, and three of them came in the week of 5 August last year.

You might argue that what goes around comes around – the Grammy-winning country singer Lainey Wilson might well proclaim in song that ‘Country’s Cool Again’, but 43 years ago Barbara Mandrell was claiming ‘I Was Country When Country Wasn’t Cool’ – but there is something different this time around. Because country today (at least the version that is shooting up the charts) is young people’s music. And it’s not just for Americans – this summer, Morgan Wallen becomes the first pure country star to headline a non-country festival in the UK, when he tops the bill at BST Hyde Park on, fittingly, 4 July. (One of the other days is headlined by Shania Twain, who has returned to a more country sound in the past few years.)

But not everyone is delighted. For 30 years Tom Bridgewater has run the British country label Loose Music. Among his discoveries is Sturgill Simpson, who went on to sign to a major label and fill American arenas. When asked why he thinks country music is on the upsurge, he’s scathing. ‘Because it doesn’t sound like country anymore. Modern country is like punk for the Hannah Montana generation.’

Whether country sounds like country is the great faultline through the modern genre. In America, traditionalists bemoan the state of country radio stations across the US using identical playlists that promote music that sounds less like country than pop, rock or hip-hop with a bit of pedal steel and fiddle dropped on top. The style known as ‘Bro Country’ (in which men sing about trucks and beer over a modern rock backing) has attracted particular disdain, but has produced some of the genre’s biggest current stars, among them Luke Bryan and Jason Aldean.

What used to be called country – serious-minded songs played on more traditional instruments – is now known as Americana, largely for marketing reasons. And even in the UK, mainstream country and Americana attract very different audiences. Bridgewater mentions going to see the singer Tyler Childers, who has quietly ascended to playing Hammersmith Apollo on his last visit to London. ‘It was noticeable that the crowd was the “bridge-and-tunnel” element,’ he says. ‘It’s the UK redneck crowd.’ Certainly, as I wrote in these pages at the time, when the breakout star Oliver Anthony played in London earlier this year, it was not at all the typical London gig crowd – Shepherd’s Bush Empire was full of people singing ‘Joe Biden’s a paedo’.

The non-metropolitan element matters. ‘There’s a rural, working-class value to it,’ says Ross Jones, editor of online country magazine Holler. ‘These artists come from small towns and they’re working on ranches and fishing – and I’m from Devon and I feel like I get that. People like songs about working hard.’

‘People never felt they could listen to country in an office – because they were too embarrassed

It’s true that the UK now has an infrastructure for country. In 2013, the annual Country To Country festival began in London, with outposts in Glasgow and Belfast. There are country radio stations, including one run by the commercial giant Absolute. There is a country airplay chart, though it’s run by the Nashville-based country label Big Machine (which launched Taylor Swift upon the world) rather than being produced by the Official Chart Company (which has its own country albums chart).

The airplay chart launched earlier this spring, and it was an explicit response to country’s rising tide over here. ‘There has been an increase in country’s UK popularity over the last eight years,’ says Alexandra Hannaby of Big Machine. ‘Taylor Swift is a big part of that – her pop fans have gone back to her country albums. And there was a massive jump when Covid hit. One theory is that country fans were late adopters to streaming, and only started doing it during Covid, so we saw a massive uptick. And we saw people who were already on streaming platforms started playing country more – as if they never felt they could in an office, because there was an element of embarrassment about listening to country.’

What’s interesting here is how this fits into a wider and rarely mentioned fact about the modern music industry: that the major labels no longer have the power to create interest in music through promotion because few people now care about the old levers of promotion – press, radio and TV. Music, thanks to social media, is global in a way it wasn’t even 15 years ago. When one talks to label executives, a common theme one hears is that popularity on social media – which those executives cannot control – is now the surest way to guarantee a hit. Songs go viral on TikTok, people share their tastes on Twitter, they post clips from shows on Instagram.

Still, though, to put Wallen, who has only played one UK show so far – admittedly, headlining to a 20,000-strong crowd at the O2 – top of the bill in front of 65,000 people seems a bit of a risk. But this is not so, insists Jim King, who oversees festivals for the promoter AEG that puts on BST Hyde Park.

‘All promoters face an element of risk with any artist booking but securing the hottest act in this genre was certainly low down in the gambling stakes,’ he says. And what will follow? ‘There’ll be many more stadium tours in this genre that the UK will get to see.’

There’s no doubt that selling out Hyde Park will be a watershed moment. But how deep will the love go? Will the crossover stars lead new fans into the bywaters of American music? Bridgewater laughs at the notion. ‘There’s no way a Morgan Wallen fan is going to know who the Handsome Family are.’

Suppress your groans: this women-only show is fascinating

In a Victorian art dealer’s shop a woman waits with her young son while the supercilious owner examines her work; behind her two top-hatted gents interrupt their inspection of a drawing of a dancer in a tutu to give her the once-over. The woman’s shabby umbrella, propped against the counter, awaits reopening in the rain outside. She knows what the dealer will say, and so do we.

Every picture tells a story, and Emily Mary Osborn’s ‘Nameless and Friendless’ (1857) summarises the plot of Tate Britain’s latest exhibition, Now You See Us. Unlike her picture’s protagonist, Osborn was herself a successful artist in a field dominated by men – not the fate of many of the artists in the Tate’s new survey of four centuries of British art by women.

Suppress your groans; this isn’t a gender-balance tick-box exercise

Suppress your groans at the prospect of another women-only show: the curators of this encyclopaedic exhibition haven’t flung together any old female artists in a gender-balance tick-box exercise. Instead they have sought out every female artist known to have practised and exhibited in Britain between 1520 and 1920 and compiled a fascinating blow-by-blow account of their struggles to achieve parity with men.

The exceptions – Artemisia Gentileschi, Angelica Kauffman and Laura Knight – only prove the rule. To succeed, women had to play men at their own game, dispelling the perception that they could only copy – that they were good at painting flowers and portraits but couldn’t work from imagination. Kauffman challenged that myth in her allegory of a female artist practising ‘Invention’ (1778-80) – commissioned for the Council Chamber of the Royal Academy from whose deliberations, as a female member, she was excluded – but copycat works by less talented successors such as Mary Beale, whose portraits borrowed compositions from Lely and Van Dyck, tend to confirm it.

If the point is to prove that women are creative equals of men, then a smaller show focused on fewer, more original women could have landed more punches. As it is, there are too many artists here who paint like clones of more famous men. It didn’t help their cause. Ethel Sands’s reward for the flatteringly Sickertian style of her ‘Tea with Sickert’ (c.1911-12) was exclusion from the all-male Camden Town Group. The show’s stand-out works avoid stylistic tics: Lucy Kemp-Welch’s dramatic ‘Colt Hunting in the New Forest’ (1897), acquired for the Tate when she was just 28; Louise Jopling’s confident self-portrait, ‘Through the Looking Glass’ (1875), newly added to the Tate’s collection; Ethel Wright’s ‘The Music Room: Portrait of Una Dugdale’ (1912), an image as decisive as its feminist subject. Like Knight, who in 1936 became the first female artist after Kauffman to be elected a full Academician, these women didn’t faff about with masculine fashion. They had the independence to keep things simple, as did the show’s poster girl, Gwen John.

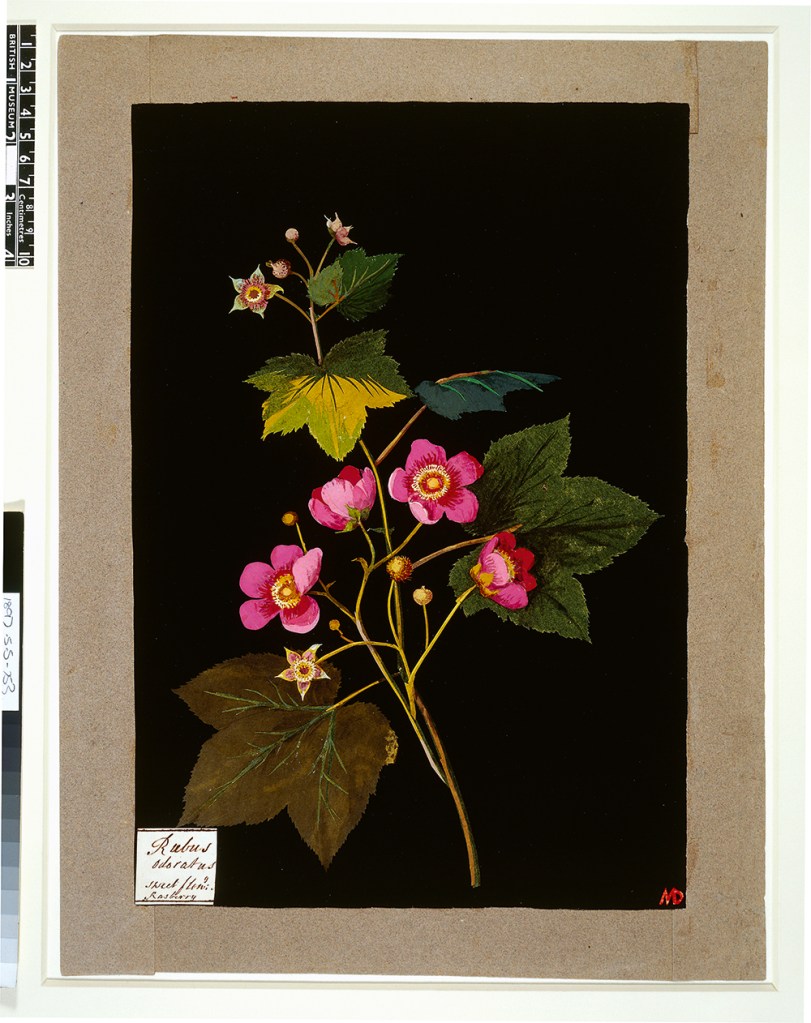

There’s another thing, non-gender-related, about the best female painters in this show: from the 18th-century Scottish portraitist Catherine Read, who studied in Paris, to the 19th-century Austrian-born Marianne Stokes, who spent time in the artists’ colony at Pont-Aven, most of them trained abroad. Stokes’s dreamlike ‘The Passing Train’ (1890), with its cloud of steam about to envelop a red-caped mystery woman in a field at sundown, is a magical invention. But imagination isn’t everything; copying has its place. The discovery of the show, for me, was the 18th-century amateur Mary Delany and the botanical collages she began making in her seventies – around the same age as Matisse began his cut-outs. Her ‘Crinum Asiaticum’ (1772-82) is as exquisite as a Karl Blossfeldt photograph and as botanically accurate: Joseph Banks swore by her reproductions. Now in the British Museum, Delany’s ‘paper mosaicks’ would have been banned from Royal Academy exhibitions as ‘baubles’, along with needlework and shell-work. (She did those, too.)

Too many artists here paint like clones of more famous men – the best avoid this

If professional status means working for money, amateur status gives an artist total freedom. An amateur woman needn’t paint like a man: she can be a complete original. Beryl Cook was a boarding house landlady when she was given the one-woman show at Plymouth Art Centre in 1975 that made her a national treasure overnight. She can hardly be described as invisible, but Cook’s jovial art, long dismissed by art world snobs as ‘popular’, is currently accruing critical bona fides in a joint exhibition at Studio Voltaire with homoerotic icon Tom of Finland. There is no doubting this woman’s powers of invention: her vision was entirely her own.

In the background of ‘Nameless and Friendless’ a clerk is making entries in a ledger, reminding us that art dealing is not just about aesthetics, it’s about what sells. Even now collectors rarely pay top dollar for art by women; Britain’s first official female war artist Anna Airy put her finger on it when she observed that galleries and buyers felt ‘safer with a man’. But if art by men still commands higher prices, art exhibitions attract more female visitors – and that’s shifting the dial.

The jaw-dropping story of the British Museum thefts

It’s August 2023 when news breaks that artefacts have gone missing, presumed stolen, from the British Museum. I’m about an hour into investigating the story for a feature when a suspect is named in the press. I know him. He’s the curator I was seated next to at a British Museum dinner nine months earlier.

Listening this week to three preview episodes of Thief at the British Museum, an electrifying nine-part series on Radio 4, I kick myself for the second time for spending most of that evening talking to the professor on my left. What can I remember of the man on my right? He was quiet. Ruddy-faced. Nothing else remarkable springs to mind.

What can I remember of the man? He was quiet. Ruddy-faced. Nothing else remarkable

The British Museum has launched legal proceedings against curator Peter Higgs, who was dismissed from his curatorial post pending the investigation. The path that led them to his name, as described in the new series, is one of the most extraordinary you are likely to hear, but not because it is convoluted – quite the contrary.

We follow that trail through the accounts of Danish gem specialist and dealer Ittai Gradel. He is, quotes presenter Katie Razzall, ‘the museum world’s answer to Sherlock Holmes’. This Danish Holmes is a gem-obsessed ‘outsider’ with a photographic memory. He left academia because he couldn’t bear sitting at the same desk and seeing the same colleagues ‘every bloody day’. One former colleague describes him as ‘quite a character’. His resemblance to Benedict Cumberbatch’s Holmes is hammed up across the episodes to an irritating degree.

Gradel happened upon the trail unwittingly. In 2010, one of his friends, a fellow antiquities dealer, came by a new supplier who purported to be an elderly man named Paul Higgins. Gradel purchased many items from his collection happily enough until some background research revealed there was no man matching his profile in public records. Before a meeting could take place, an email arrived to say that Higgins had died.

Fast-forward a year, and Gradel is delighted to find a new seller on eBay. He goes by the name of Sultan1966 and offers gems worth £5,000 for as little as £15. Gradel is in cameo Eden until, one day some years later, one comes up for sale that he has seen before. How could an object catalogued as belonging to the British Museum possibly be listed here?

The gem isn’t the only thing that’s familiar. Gradel suddenly realises that packaging from another gem he’d ordered from Sultan1966 carried the same name as the earlier supplier who had reportedly died. More bewilderingly still, Gradel’s Paypal receipts reveal a marginally different name: Peter Higgs. Could he be synonymous with the British Museum curator who was born in 1966 and goes by Sultan1966 on Twitter?

Since Higgs has not been charged with anything to date – and his family has protested his innocence – it will be interesting to see how far the BBC probes his life and possible motivations in the remaining six episodes. It certainly sounds as if the Museum will come under scrutiny. Gradel says as much when he describes the strangeness of uncovering a crime to which its staff are oblivious from the comfort of his study in Denmark.

Against all efforts to present him as a weirdo engaged in esoteric research – references to his ‘specialist knowledge about history’ and ‘dusty books about the ancient world’ will grate on anyone with an ounce of intelligence – Gradel emerges from this otherwise gripping series as a normal guy determined to do the right thing. He’s neither Sherlock Holmes nor Miss Marple. His story is that of a rare somebody who keeps his eyes wide open.

Poet Ian McMillan is another advocate of keeping one’s eyes open. While Roman gems tantalise Gradel, park benches, buses and rubber bands are more McMillan’s bag. The Beauty of Everyday Things, which the Yorkshireman presents on Sunday, takes the form of a one-off, half-hour monologue in which he describes what he sees while strolling through his day.

Before dawn he notices tinsel overflowing from a bin, a smell of smoke and a stray rubber band which – this reflects his optimism – reminds him of the moon. Debussy’s Clair de Lune begins to play. ‘Light,’ reflects our poet, ‘is starting to wash the sky’s face.’ Later, he spots fungus that reminds him of his uncle’s ears, and a hanging basket with nothing in it.

You need to be in the right mood for this kind of thing. I am all for the sentiment – get off your phone, look at the world, be alive – but the process of spelling it out can sound strange. That’s not to say there aren’t some beautiful images and turns of phrase. McMillan, like his idol Georges Perec, is an interesting wordsmith, and I recommend sticking with it. But I came away feeling that this exercise is best conducted inside one’s own head.

The new Mad Max film is a betrayal of everything that made Fury Road so good

Action films are boring. This isn’t really an opinion, it’s just demonstrably true. Try it for yourself: put on any high-octane, orange-and-teal action movie from the last 15 years and see how long it takes before you start automatically fiddling around with your phone. I can usually make it about five minutes. This is weird. I can deal with all the incredibly sedate cinematic vegetables just fine, but as soon as there are gunfights or chases involved I get distracted. I think I know why.

The real betrayal of this Mad Max sequel is that it’s full of talking

Action directors know that they’re competing with the sensory equivalent of a crackpipe in every pocket, so they do whatever they can to make their films as attention-grabbing as possible. Everything comes out slick, shiny, computerised; a lot of the time, each individual shot only lasts for a few seconds, in case you get tired of looking at one thing for too long. They’re desperate not to bore us. But the overall effect is of loud, manic, basically unconnected digital images swimming in front of your eyes – which happens to be the exact same effect you get from scrolling mindlessly on your phone. So you may as well just look at your phone.

In a way, CGI has ruined the dumb action film. When anything is possible, nothing is ever really impressive. When an essentially fictional camera can swoop through a simulated environment at will, the image loses any relation to the actual process of looking and it’s hard to maintain any visual interest. You can throw in as many explosions as you like; it still feels like watching a screensaver.

But it wasn’t always like this. You can go back and watch the magnificently dumb original Matrix from 1999: there’s some computer-generated stuff happening around the edges, but most of what you’re seeing onscreen is a human body being dangled on wires by a Hong Kong choreographer, and it looks visceral and real. In the 2003 sequels, that’s been replaced with CGI, and it looks like those animations they play at the bowling alley.

Anyway, one of the great recent exceptions to this rule was 2015’s Mad Max: Fury Road, which was a lot of things, but not boring. The entire film essentially consists of one extremely long car chase through a post-apocalyptic Australia up until the end. As soon as you sit down, you’re battered in the face by one audacious practical effect after another. Real buggies covered in rusty metal spikes, real big rigs decorated with human skulls, real explosions in a desert somewhere. Even if the skulls are plaster, the effect is genuine. By the end, I felt myself bludgeoned into a kind of meaty pulp, about the same consistency as gravy left in the fridge overnight.

The film’s other great virtue was its refusal to explain what it was doing. The title character barely spoke five words in the entire two-hour runtime. The plot revolved around a general called Furiosa trying to steal away the harem of a bloated warlord called Immortan Joe and take them to somewhere called the Green Place, but even that was mostly told through firefights instead of dialogue. Meanwhile there were weird stilt-walkers in the dead marshes, legions of cancerous, white-painted warriors kept alive by constant blood transfusions from their prisoners, and an obscure religious cult based on the principles of eternal rebirth and sniffing paint. None of this was ever explained, which didn’t matter at all. They were great images. Great images work by themselves.

In fact, as part of the writing process for Fury Road, director George Miller produced pages and pages of backstory for every character. I’m sure this is part of what made the film work: it might have been proudly dumb, but it wasn’t stupid; there was an internal reason for everything that happened. But we, as viewers, do not need to see that backstory. It’s much more fun to just be thrown into the chaos of this world. Unfortunately, Miller seems not to agree.

Since he had the backstory, why not adapt it? Which is why we have Mad Max: Furiosa. When the trailer was released, it sparked an immediate backlash: this prequel seemed to be stepping away from practical effects and leaning more heavily on CGI. Which it does, to its detriment – but the real betrayal is that this thing is full of talking. Long dialogues in which the characters explain themselves and their motivations to each other. Near the end, an enormous, climactic war between two rival chieftains is skipped over in a five-second montage so that two characters can have a conversation about the futility of revenge.

It’s all fine. Anya Taylor-Joy is fine as the vengeful heroine. Chris Hemsworth is fine as the lightly maudlin villain. The set-piece battles we get are fine. We see some of the mysterious locations mentioned in Fury Road, and those are fine, too. There are a lot of people who will be really into this sort of thing: there’s a whole cottage industry of YouTube explainers, delving into the backstories and lore of every big entertainment franchise, neurotically disassembling everything into its moving parts. They like things to be explicable. But I felt a strange urge to look at my phone instead.

BBC1’s new Rebus is the kind of TV detective they just don’t make any more

Imagine a new series of Morse in which the real-ale-quaffing, jag-driving opera buff is turned into a speed-snorting mod on a pimped up Lambretta. Or – this one I’d actually like to see – jeune Poirot, featuring a clean-shaven habitué of fin-de-siècle Brussels absinthe dives. This may give you an inkling as to how upset one or two Rebus fans are about the Edinburgh detective’s latest TV incarnation.

Confusingly titled Rebus – as opposed to, say, Punk Rebus or Wee Rebussie – the series depicts a protagonist quite a bit younger than his former TV incarnations, grumpy, dishevelled Ken Stott and a mite-too-smooth John Hannah. Still only at the detective-sergeant stage of his career, he is a lot more aggressive – like maybe Begbie from Trainspotting would be in the unlikely event he ever joined the police – with a hair-trigger temper and a drinking problem.

This isn’t so much a faithful adaptation as a controlled demolition

This isn’t so much a faithful adaptation of Ian Rankin’s crime novels as a controlled demolition. I say ‘controlled’ because Rankin himself gave screenwriter Gregory Burke, author of the hit play Black Watch (based on interviews with Iraq war veterans), carte blanche to reimagine Rebus as he wished. And apparently he’s very happy with the result.