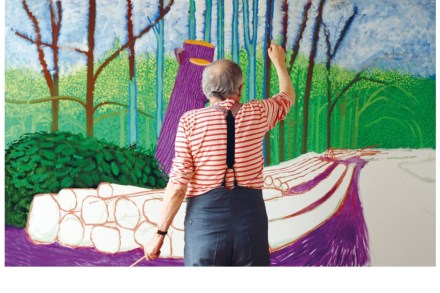

A Bigger Message: Conversations with David Hockney by Martin Gayford

Like his contemporary and fellow Yorkshireman, Alan Bennett, whom he slightly resembles physically, David Hockney has been loved and admired throughout his lifetime. He painted one of his greatest works, ‘A Grand Procession of Dignitaries in the Semi-Egyptian Style’ in 1961 while still at the Royal College of Art. He has dazzled, surprised and often upset the world of art ever since. Picasso aside, he is the wittiest modern painter, in the sense not just of being funny, but intelligent; a whole history of Western art is both contained and extended by his originality. For example, it was both funny, and in the 1960s brave, to apply Boucher’s soft pornography