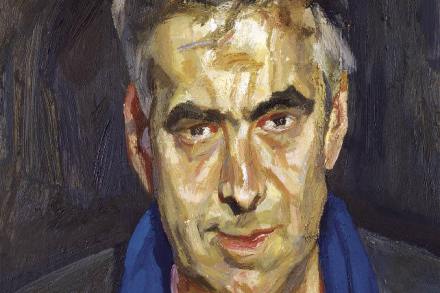

Folkie supergroup

The Fence Collective is a loose association of singers, musicians and songwriters, at least a few of whom live in and around Anstruther in Fife. The Fence Collective is a loose association of singers, musicians and songwriters, at least a few of whom live in and around Anstruther in Fife. Anstruther is a fishing village and not the first place you’d go looking for a revolution, but the Fence Collective has other ideas. It hosts events and festivals and even has its own record company. I was brought up in Fife, so when I heard about Fence I was curious. Soon thereafter I was part of the congregation and singing