St Paul’s Cathedral is quite rightly something of a national obsession. No other building has protected ‘view corridors’ as a result of legislation in 1935, when new building regulations allowed the surrounding buildings — notoriously a telephone exchange to the south — to overtop the cathedral’s cornice line. These corridors, extending like an unseen net as far afield as Richmond Hill, make architects unaccountably cross, as if they were an unfair curb on the alliance of art and Mammon. Thank God they are there, and that the tallest buildings, springing up once again like genetically modified beanstalks, are at least corralled east of Bank.

St Paul’s Cathedral is quite rightly something of a national obsession. No other building has protected ‘view corridors’ as a result of legislation in 1935, when new building regulations allowed the surrounding buildings — notoriously a telephone exchange to the south — to overtop the cathedral’s cornice line. These corridors, extending like an unseen net as far afield as Richmond Hill, make architects unaccountably cross, as if they were an unfair curb on the alliance of art and Mammon. Thank God they are there, and that the tallest buildings, springing up once again like genetically modified beanstalks, are at least corralled east of Bank.

What, then, does an architect do when asked to build in the afternoon shadow of St Paul’s east end? In 1953, Victor Heal, a decent but dull conservative, designed Bank of England Chambers on a large bombsite, completed in 1960. Not long afterwards, Modern architecture claimed a victory when similarly ‘respectful’ designs for a new Choir School were rejected and a competition held, resulting in the present design by Architects Co-Partnership. The author of the scheme was Leo de Syllas, who was killed in a car accident soon after, so it fell to another partner, my father Michael Powers, to carry out the scheme. It was admired at the time, although Ian Nairn, the greatest critic of the 1960s, called it ‘over-serious, in the way that a really responsible senior civil servant can be’.

Land Securities saw a development opportunity and Heal’s homage to Wren, built of red brick and Portland stone, failed to make the grade for listing, unlike its neighbour, Sir Albert Richardson’s Bracken House. In its place we have Jean Nouvel’s alternative, the so-called ‘Stealth Bomber’ (please say that in the voice of Peter Sellers as Inspector Clouseau). In its way, the Choir School attempted the same trick, keeping as low as possible and dividing its accommodation into three main blocks, so that the axial view from the east would not be blocked.

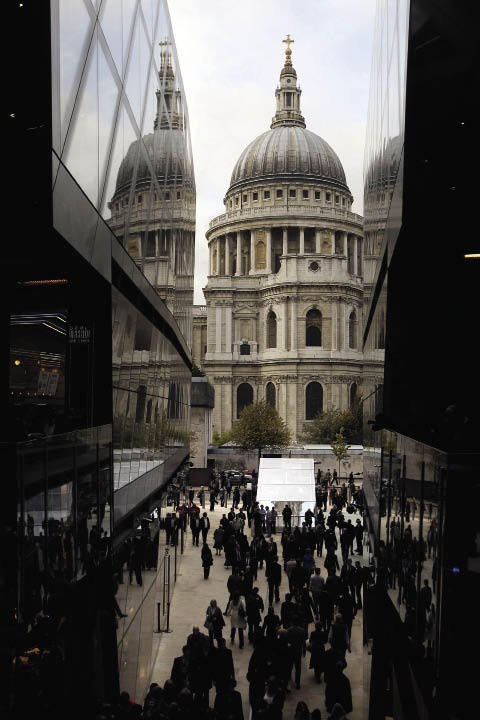

One point in favour of Nouvel’s new New Change building is the way it finally makes sense of this gesture by framing the east end and dome in a dramatic cleft that cuts from the street to the central atrium, in which view the Choir School is hardly seen. There are other points in favour of this changeling of New Change. The sheer glass skin can look dull and pointless, but it can also reflect the sky and really play the dissolving trick that modern architecture promises but seldom delivers. The beetling cliffs of glass, leaning outwards from the base, help to create the illusion. The roof has a terrace that, unlike most City rooftops, can be visited by the humble public. For spectators aloft on the Stone Gallery of St Paul’s dome, it makes a difference whether the rooftops are designed to be seen or simply left as random assemblies of lift gear and air-conditioning outlets. One just hopes that it won’t be turned into an exclusive club or bar too soon, as inevitably seems to happen with London roof gardens.

Like its predecessor on the site, One New Change is too much of a good thing, however, and it is a severe test of modern architecture’s ability to provide street entertainment. Along Cheapside, with its unrelieved cliff of glass, the ingenuity dies away. The ‘correct’ view that still prevails among most architects is that ‘façades’ have no place unless they ‘honestly’ convey some truth about what goes on inside the building.

One can see why, around 1920 after a century or more in which the elevation was the principal issue in judging a building, it was refreshing to turn the focus elsewhere, but such corrective justification is long gone, and in the process most architects have lost the ability or the will to design elevations that hold the eye. Even Victor Heal knew more about it than any architect working in the City today, although his contemporaries, Donald McMorran and George Whitby, designers of the Wood Street Police Station and the Old Bailey extension, were Mozart to his Salieri. What is missing from today’s architecture, despite plenty of exemplars from within its own tradition, is a collective sense of how it could be done and a desire to experiment and outdo each other.

Comments