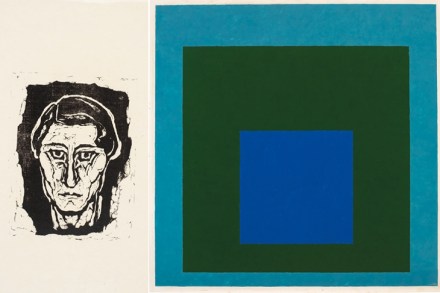

Albers the austere

The German-born artist, Josef Albers, was a contrary so-and-so. Late in life, he was asked why — in the early 1960s — he had suddenly increased the size of works in his long-standing abstract series, ‘Homage to the Square’, from 16×16 inches to 48×48. Was it a response to the vastness of his adopted homeland, the United States? A reaction to the huge canvases used by the abstract expressionist painters in New York? ‘No, no,’ Albers replied. ‘It was just when we got a station wagon.’ In Charles Darwent’s new biography, Albers (1888–1976) comes across as a man as frill-free as the art for which he’s famous. Apparently, he held