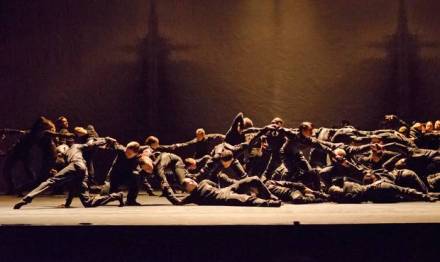

Alice in Wonderland at the Barbican reviewed: too much miaowing

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson loved little girls. He loved to tell them stories, he loved to feed them jam, he loved to set them puzzles, and he loved to take their photographs. On 25 March, 1863, he composed a list of 107 prepubescent portrait subjects, arranged alphabetically by forename. Below the Agneses came the Alices, including Alice Liddell, the little girl for whom he created Alice in Wonderland. Mostly good-mannered, occasionally lachrymose and stuffed full of half-remembered governess-led learning, the fictional Alice displays behaviour quite out of step with her age. Instead of doing what she is told to do by the creatures she meets, she behaves like an adolescent (though