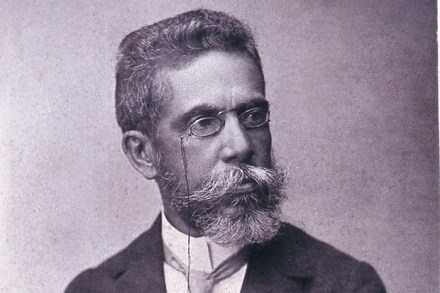

Rio’s rococo genius

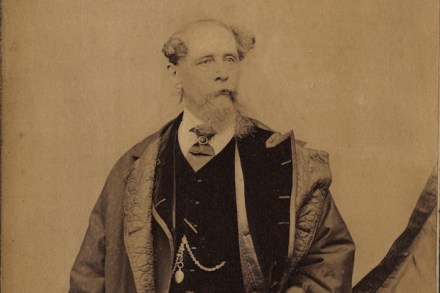

The surname is pronounced ‘M’shahdo j’Asseece’. There are also two Christian names — Joaquim Maria — which are usually dispensed with. K. David Jackson, professor of Portuguese at Yale, confines himself to ‘Machado’ and has invented an adjective ‘Machadean’. Stefan Zweig, who committed suicide in the very Machadean town of Petropolis, called him ‘the Dickens of Brazil’ which is not true — he has not Dickens’s range or sustained ebullience. I used to say he was the Gogol of Brazil — particularly in his short stories — but re-reading Dom Casmurro, one of the five novels of Machado’s maturity, I can see he has not Gogol’s hatred, which gives the