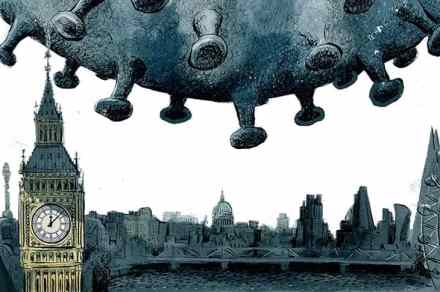

In defence of the 15-minute city

At the end of last year, the subject of the ‘15-minute city’ began to creep into neighbourhood WhatsApp groups, interrupting the usual discussion of lost cats, car crime and blocked drains. Oxfordshire County Council had proposed a traffic-zoning scheme to reduce car usage in the city – and suggested that to address unnecessary journeys, every resident should have ‘all the essentials (shops, healthcare, parks) within a 15-minute walk of their home’. But critics up and down the country hit on the proposals as an example of the ‘international conspiracy’ and ‘tyranny’ of the 15-minute city – which, they warned, is probably coming to a neighbourhood near you soon. Although the