At the end of last year, the subject of the ‘15-minute city’ began to creep into neighbourhood WhatsApp groups, interrupting the usual discussion of lost cats, car crime and blocked drains. Oxfordshire County Council had proposed a traffic-zoning scheme to reduce car usage in the city – and suggested that to address unnecessary journeys, every resident should have ‘all the essentials (shops, healthcare, parks) within a 15-minute walk of their home’. But critics up and down the country hit on the proposals as an example of the ‘international conspiracy’ and ‘tyranny’ of the 15-minute city – which, they warned, is probably coming to a neighbourhood near you soon.

Although the term only gained traction four years ago, the 15-minute city is nothing new in town-planning theory. The idea of urban areas where amenities can be reached within a 15-minute walk or cycle has been shaping neighbourhoods across Europe for decades, and there are flourishing examples across the UK and beyond. As well as Oxford, governments in locations including Bristol, Birmingham, Canterbury, Ipswich and Sheffield have recently said they hope to implement a 15-minute city plan.

Yet over the past few months, conspiracy theorists have condemned this urban-planning model as a ‘Stalinist’ method of controlling the population by stopping free movement and infringing residents’ rights, claiming the ultimate goal is to confine people to their neighbourhoods. It was called an ‘international socialist concept’ by Conservative Party MP Nick Fletcher during a parliamentary debate last month, and arguments over its merits (or lack thereof) are raging on Twitter. So what’s the truth?

Jorge Beroiz, a design specialist at architect CRTKL, says that the modern 15-minute city theory is motivated by the goal of cultivating vibrant local neighbourhoods and reducing carbon emissions. ‘Historically cities have been primarily designed around cars, but the 15-minute city puts pedestrians first,’ he explains. ‘The aim is not to seal off communities and limit them to a 15-minute boundary.’

The concept has been evolving since the 1920s, when American Clarence Perry championed the idea of walkable cities. But it was Franco-Colombian Carlos Moreno of Sorbonne University in Paris who is credited with coining the term ‘15-minute city’ in 2019. The city’s mayor, Anne Hidalgo, incorporated it into her 2020 re-election campaign, and since then Paris has banned cars from parts of the Seine and built new cycling routes.

During the pandemic, the appeal of walkable neighbourhoods was brought into focus as many urban dwellers reset their routines, cut out the commute and rediscovered what was on their doorsteps. In some areas, newly pedestrianised seating areas outside restaurants went on to become permanent features – as did hybrid working patterns. All of this has contributed to a shift in what people want from the places in which they live. A recent YouGov survey found that 62 per cent of people would like their area to become a 15-minute neighbourhood, naming easy access to bus stops, post boxes and medical facilities as their priorities. Which makes moves in this direction sound less like a conspiracy and more like paying attention to what communities actually want.

What the critics also seem to have overlooked is that in many parts of the UK and abroad, the 15-minute city concept is working well already. One established self-sufficient community is Poundbury in Dorchester, championed by King Charles, who coined the term ‘urban village’ 20 years ago. And there are many more in the planning, including Fawley Waterside, a live-work-play community on the site of the former Fawley power station on the Solent. The self-contained, predominantly car-free town will include 1,500 new homes for sale next year.

At The Phoenix in Lewes, East Sussex, the focus will be on shared amenities within a 15-minute walkable radius. These will include a mobility hub, electric car club, communal gardens and community canteen – along with 700 homes on the brownfield site, running entirely on renewable energy.

Another developer, Ballymore, applies the 15-minute city principles to all new schemes, explains sales director James Boyce. ‘People want easy access to GP surgeries, food shops and green space, but the challenge is to ensure that people are able to move between them without having to get in the car,’ he says. ‘On top, of course, is creating a public realm that offers people the opportunity to stop, dwell and socialise.’ At the Brentford Project, the firm’s major regeneration scheme in west London, 876 new homes (from £470,000) will sit alongside a revitalised high street reconnecting it with the waterfront.

One vibrant 15-minute neighbourhood that has evolved over two decades is Wembley Park – an 85-acre live-work space around the stadium with more than 5,000 new homes by Quintain. A newer example can be found in north London’s Brent Cross Town, a mixed-use regeneration scheme from Related Argent with 6,700 new homes (from £400,000), offices, shops and restaurants next to Brent Cross Shopping Centre. Connectivity – another essential for 15-minute cities – is via a new Thameslink station.

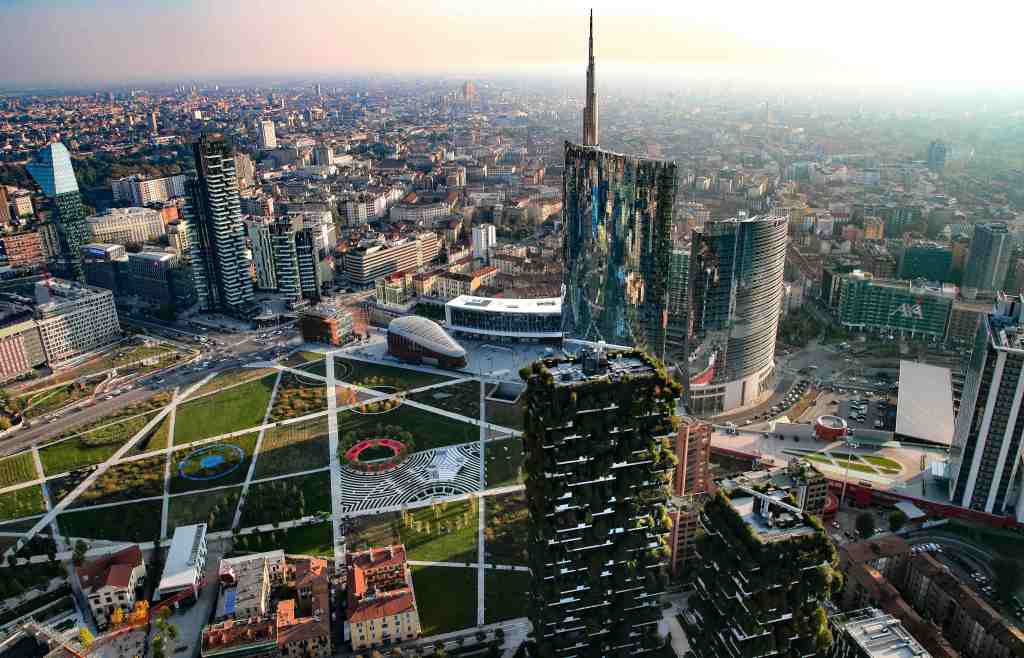

Beyond the UK, there are plenty more examples of thriving 15-minute cities, too. Milan’s futuristic miniature live-work city of Porta Nuova has been growing since 2005, and is home to the distinctive Bosco Verticale complex – two ‘vertical forest’ apartment towers. Kelly Russell Catella of developer COIMA says: ‘Placing nature and humans at the centre of all our developments leads to the creation of more sustainable and vibrant communities.’

In Athens, the city’s old international airport is an impressively hi-tech 15-minute smart city, The Ellinikon, and the country’s largest regeneration project. Poland’s first ‘15-minute city’ is Pleszew, south of Poznan, which has a new network of bike paths that connect schools, commerce and recreation; while Copenhagen’s harbourfront Nordhavn will follow a ‘five minutes to everything’ model. Meanwhile Barcelona’s Superblock model plans to divvy up the city into 503 nine-block clusters to provide more space for people and less for cars.

Sweden’s ‘one-minute city’ has taken the approach to a hyper-local level, with the Street Moves initiative by Think Tank ArkDes transforming individual streets into social hubs and green ‘parklets’. They provide a toolkit of street furniture ready for installation with planters, seating, play spaces and bike racks. Perhaps that’s another idea for a lively debate on the neighbourhood WhatsApp group.

But with this many success stories around the world and a growing need for communities to cut their car use, it seems unlikely 15-minute cities are going anywhere – however much the concept gets hijacked by conspiracy theorists.

Comments