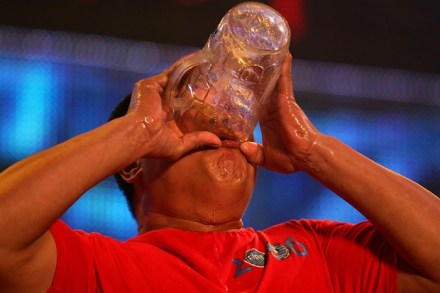

What shall we do about Neknominate?

I wonder if we should start our own Spectator Blog NekNominations? Open to bloggers and readers. I nominate Daniel Maris to drink a small glass of Pinot Noir while watching the early evening news. And Alex Massie to drink a flagon of Teachers while standing on the up line somewhere between Edinburgh and Alnmouth. Maybe on that big bridge over the Tweed. No need to post any photos or film. I’ve written about this latest internet craze for the mag this week: it is the usual carefully and copiously researched investigation, devoid of bigotry and offensiveness. At least five people have died so far taking part in Neknominations and there