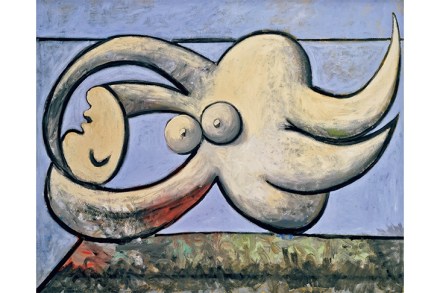

Année érotique

By 1930, Pablo Picasso, nearing 50, was as rich as Croesus. He was the occupant of a flat and studio in rue La Boétie, in the ritzy 8th arrondissement, owner of a country mansion in the north-west, towards Normandy, and was chauffeured around in an adored Hispano-Suiza. He stored the thousands of French francs from the sale of his work in sacks deep inside a Banque de France vault, like a ‘country bumpkin who keeps his savings sewn into his mattress’, someone once said. Married since 1918 to one of Sergei Diaghilev’s ballerinas, Olga Khokhlova, Picasso was coming to dominate the art world in a manner no painter has before