The mystery of Rapa Nui’s moai may be solved

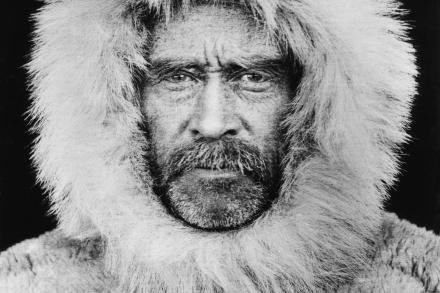

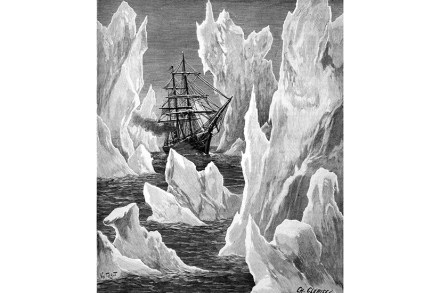

Boris Johnson claims that in his first year at Oxford he attended just one lecture. Delivered in the crepuscular gloom of the Pitt Rivers Museum, it was about Rapa Nui, the tiny Pacific island 2,200 miles from mainland Chile. As a boy, Johnson had read the Norwegian adventurer Thor Heyerdahl’s Aku-Aku: The Secret of Easter Island and had become obsessed. No wonder. For although Rapa Nui – or Easter Island – is only half the size of the Isle of Wight, it has a haunting history teeming with questions. Who first discovered this speck in the Pacific? How did they get there? How did they manage to settle in this