Mother of mysteries: Rosarita, by Anita Desai, reviewed

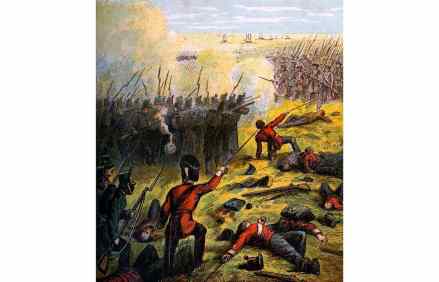

There are other reasons beyond shortage of time (the acclaimed Indian novelist Anita Desai has just turned 87) to write a novella; the genre is as attractive and prestigious as it is fashionable. The deceptively slender format can briskly encompass whole worlds and histories, or alternatively, like the short story, depend on strict excisions and limitations for its effects. Rosarita does both. A young woman, Bonita, addressed as ‘you’ throughout, is taking time out from her Spanish-language studies and relaxing on a park bench in the historic centre of San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. Education has been her means of escape from the domineering family structure back in India that