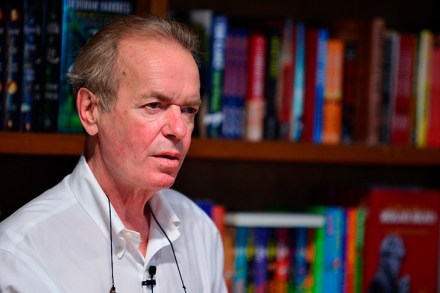

Opposites attract: Just Like You, by Nick Hornby, reviewed

Babysitters are having a literary moment. Following Kiley Reid’s debut Such a Fun Age, Nick Hornby is the latest author to mine the potential for blurred lines and crossed boundaries bred by the employer-childminder dynamic. Throw race, class, sex and Brexit in the mix, and you have a juicy plot that’s both vintage Hornby and totally contemporary. Hornby has been chronicling north London’s romantic and cultural obsessions since 1992, and Just Like You doesn’t stray from home turf. It is 2016 and Joseph, a black 22-year-old from Tottenham, works Saturdays at an Islington butcher. While enduring the innuendos of drooling white women, he meets pretty, unaffected Lucy, who asks him