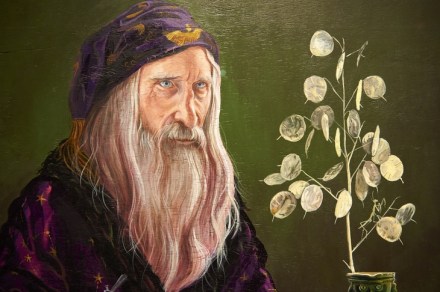

Into the woods

This is a novel about trees, written in the shape of a tree (eight introductory background chapters, called ‘Roots’; a ‘Trunk’; a ‘Crown’; some ‘Seeds’), and which unashamedly references every tree you might half-remember, from Eden to Auden (‘A culture is no better than its woods’). It revolves around various efforts to save trees, whether by seedbanks or political activism, and details the ways in which its group of protagonists becomes radicalised and willing to put their lives on the line, or even kill, to save the few remaining patches of old forest in the USA. One of these protagonists, Olivia, turns towards the forest when she has a near-death