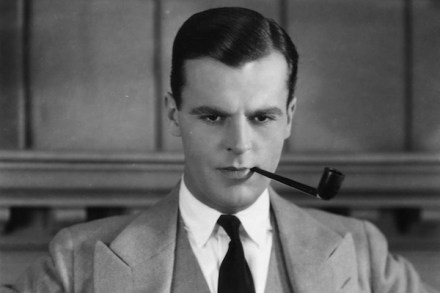

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s other ‘great’ character

It is perhaps fitting — given his lack of fame and success — that many of you will have never heard of Pat Hobby. Hobby was a character who featured in a number of F. Scott Fitzgerald short stories towards the end of the author’s life, when he was working in Hollywood. Hobby is a forty-nine year old scriptwriter whose best days are long behind him. Rather than reaching out for a green light at the end of a dock in Long Island, Pat is forever scrabbling around for his next ten dollars in order to buy another drink or pay off his bookie. Regardless of whether he employs honest