Strewn with foreign bodies

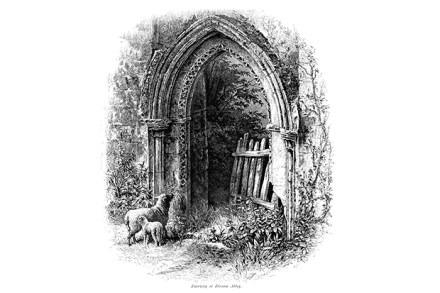

Ghosts of the Past by Marco Vichi (Hodder, £18.99) is unashamedly nostalgic in tone. The title could not be more apposite. The action takes place in 1967, when Inspector Bordelli of the Florence police force is called to a house where a wealthy industrialist has been run through with a sword. Each member of the family is acting suspiciously, as are the various colleagues and associates of the deceased. Bordelli’s life is further complicated when an old friend, Colonel Arcieri, turns up in dire trouble and needing protection. The case unfolds in a slow haze of interviews and recollections. Vichi takes his time to explore Bordelli’s mind, his thoughts and