Nigel Farage’s diary: Comfort for Cameron, and the wonders of German traffic

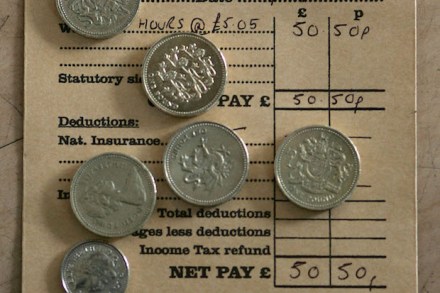

What a week! I was thrilled to have a chance to confront Nick Clegg but my excitement was tempered with disappointment that neither Cameron nor Miliband agreed to take part — although both were invited. I’d love to have challenged Miliband about the effects of uncontrolled immigration: wage compression, for instance, and the erosion of job opportunities within working-class communities. Why did he chicken out? My bet is he knows these facts are unanswerable. Cameron is, by all accounts, having kittens about Ukip but I think I can set his mind at rest. Our current wave of support seems to be thanks to working-class former Labour voters, which makes perfect sense.