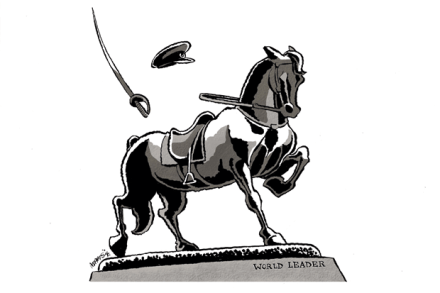

Tariff turmoil: the end of globalisation or a blip in history?

17 min listen

Globalisation’s obituary has been written many times before but, with the turmoil caused over the past few weeks with Donald Trump’s various announcements on tariffs, could this mark the beginning of the end for the economic order as we know it? Tej Parikh from the Financial Times and Kate Andrews, The Spectator‘s deputy US editor, join economics editor Michael Simmons to make the case for why globalisation will outlive Trump. Though, as the US becomes one of the most protectionist countries in the developed world, how much damage has been done to the reputation of the US? And to what extent do governments need to adapt? Produced by Patrick Gibbons.