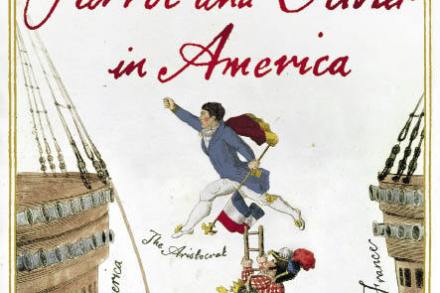

Adventure with a difference

Probably my opinion of this bold book is worthless. Peter Carey, having decided to write a novel about Alexis de Tocqueville’s visit to the United States in 1831-2, read, among many other works, my biography of Tocqueville, which was published two years ago in, he says, ‘the nick of time’. He is kind enough to call it ‘delightful’, and has plundered it assiduously. What I myself find delightful is the way in which Carey has picked up the signals. I never expected such a close, intelligent reader, and I’m glad to think my work has been of use to him. But this does not make me a dispassionate reviewer. And