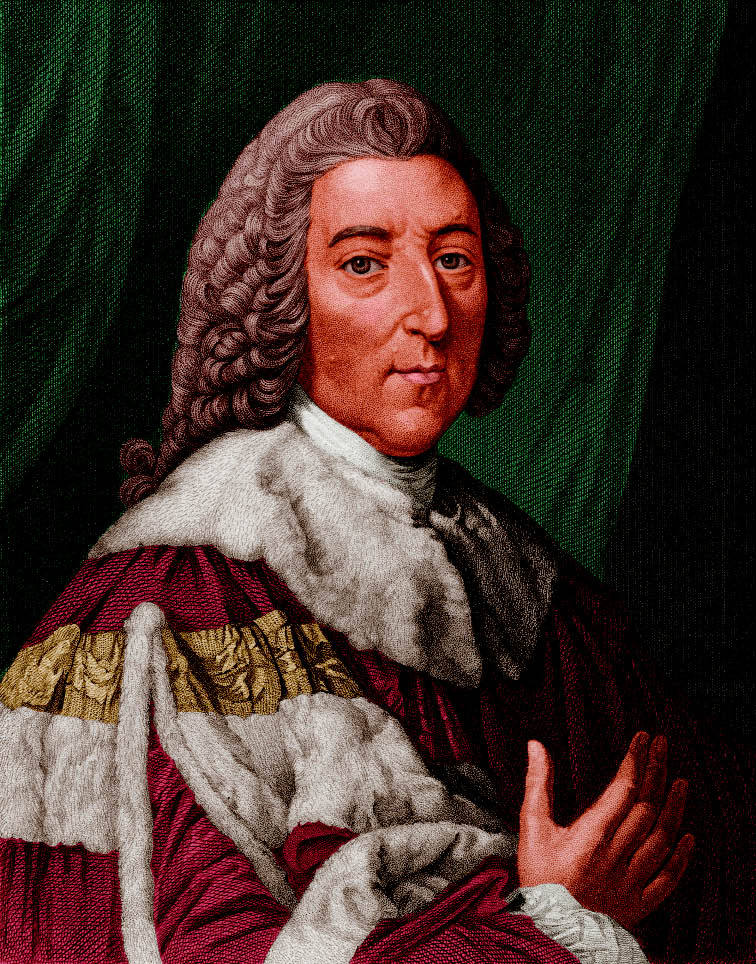

William Pitt the Elder, Earl of Chatham was hailed by Victorian schoolboys as the man who made England great. He was the patriot leader, the minister who steered the country through the Seven Years War, climaxing in the Year of Victories of 1759. General Wolfe heroically captured Quebec, British troops helped Frederick the Great of Prussia smash the French at the battle of Minden, and the British navy decisively defeated the French at Quiberon Bay. England emerged as the greatest power not just in Europe but in the world, and Pitt was the hero.

In fact, Pitt’s reputation was wildly inflated. The war was fought by soldiers making decisions on the spot — it had to be, as letters took several weeks to reach England. Pitt neither planned nor financed the war. Most of his strategic initiatives failed. Back in London, he made the speeches and took the credit. He was, as Edward Pearce argues in this revisionist biography, the show business man of war. As historians have recognised for some time, Pitt’s bubble is overdue for pricking.

Pitt was the grandson of the India merchant ‘Diamond’ Pitt — so-called because he bought a diamond the size of a hen’s egg at a rip-off price in India and sold it at a 450 per cent profit to the King of France. William Pitt drifted into parliament aged 25, sitting for the family borough of Old Sarum, which had all of five voters. He made a reputation as a critic of prime minister Walpole’s corrupt political system but, as Pearce points out, this was a matter of expediency rather than conviction. He belonged to the clique or faction which revolved around the Grenville family, and because they were in opposition, they needed a cry. Pitt was their leading orator, but his speeches, says Pearce, were heavy and dull.

Pitt excelled as a political operator. When the British navy lost Minorca to the French in 1756, leading to the scapegoating of the unfortunate Admiral Byng, Pitt emerged as the leader of the patriotic party. He clamoured for war. More to the point, he refused to work with any of the king’s ministers, forcing George II (who disliked him) to appoint him to the top job. In 1757 the Pitt-Newcastle ministry was formed, which headed up the war.

Pitt’s political world was one of complex manoeuvres and shifting alliances within a small group of aristocratic politicians, most of whom seem to have been called Grenville. This is confusing at the best of times, and Pearce’s account does not elucidate. He writes the story in the style of a political column. This is the form he perfected as a journalist. His brilliant, sideways-skewering political columns worked because his readers knew who he was talking about. It’s more problematic applying this allusive, oblique style to 18th-century politics, which is a closed book to most people except for specialists. Much of the narrative is pretty heavy- going. For readers who are not versed in the subject, it may be almost impenetrable. After a bit one does begin to wonder who exactly this book is written for.

Pearce’s treatment of the Seven Years War is more readable. But there are problems here too. Pitt is invisible for much of the narrative. Pearce seems more interested in telling the story of the heroic General Wolfe or the dramatic battle of Minden. He can’t make up his mind whether he is writing a book about the war or a book about Pitt. Subtitling the book ‘Man of War’ doesn’t really solve the problem. No doubt Pearce is right to say that Pitt’s role in the war has been exaggerated. But to prove the point he needs to look a little more closely at what Pitt did at his desk, at whom he talked to, at the process of decision-making and at how the cabinet worked.

It’s hard to disagree with Pearce’s view that Pitt was ‘a demagogue, highly intelligent but incapable of detail, self-absorbed, fascinated by power’. Not very different, in other words, to the political leaders of today. Pearce’s debunking tells us almost as much about the 21st century’s disenchantment with politicians as it does about Pitt himself.

Pearce has immersed himself in the secondary sources, but has spent little time in the archives. The book is polemic, rather than biography in the usual sense. Only on page 298, 50 pages from the end, does Pearce tell us, in characteristic style, that ‘it is worth pausing the caravan of high policy and low intrigue to look at Pitt the man, husband, father, legatee, landowner, garden-extender and house-improver’. Even then, he gives only a page or two to Pitt’s life outside politics.

Aged 40, Pitt married Hester Grenville, and found himself at the heart of the Grenville/Pitt connexion. It is through the letters of women that the world of the 18th-century political elite has been brought to life, in books such as Stella Tillyard’s Aristocrats. But Pearce has little to say about Pitt’s marriage, except that Hester supported him. What sort of a father the irascible Pitt was to his prodigy son, William, the Younger Pitt, is not really considered.

Then there’s the matter of Pitt’s health. From the age of 14, he suffered from crippling attacks of ‘gout’, and he often appeared on crutches and wearing bandages. He was prone to episodes of insanity. In office as prime minister in 1767 he was incapacitated for six months by madness, probably manic depressive illness, and he seems to have become almost catatonic.

Pitt was a showman to the end. His last performance was the most dramatic of all. Suffering from gout, he appeared in the House of Lords, swathed in flannel, wearing velvet boots, a tall, cadaverous figure supported by his son William, then a Cambridge student. In the middle of a speech, spouting a torrent of inaudible rage against the French, he collapsed with a seizure. He died a few weeks later. He was a consummate actor. Pity he wasn’t a more attractive or interesting man.

Comments