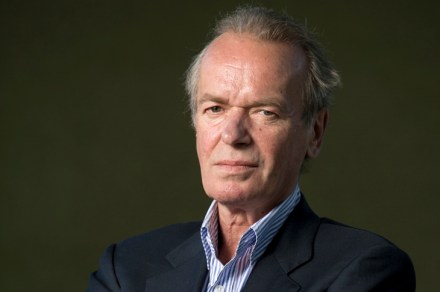

Frederic Raphael settles old scores with a vengeance

Last Post is a collection of reminiscences, anecdotes and a settling of old scores by Frederic Raphael in the form of imaginary letters to many of the people who have been part of his long life. You might expect a nonagenarian’s critical faculties to have ‘mellowed by the stealing hours of time’, but far from it. Raphael’s intelligence and acerbic wit are undiminished. George Steiner suffers a sustained attack for being gauche, malicious and too obviously ambitious Those who have crossed his path will be aware of his ability to ‘verbalise easily’ and, as he himself confesses: ‘It is one of my failings that I know how to hurt people.’