New literary award launches. But is the Folio Prize just a pretentious version of the Booker?

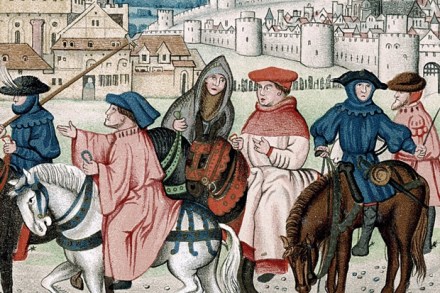

The British Library isn’t the first place I associate with contemporary fiction. For me, it’s about the Tudor manuscripts: the support and expertise of the manuscript room staff is second to none, and to the academic mind, few thrills compare to finding Elizabeth I’s distinctive handwriting on an unexpected document, or deciphering treacherous correspondence in a prayer book. But DBC Pierre it sure ain’t. Yet under the alert leadership of Roly Keating, the man who put BBC Four on the map, the British Library is now carefully fostering a commitment to living writers, not merely the dusty and dead. In a masterstroke of curation, when I leave the manuscript room,