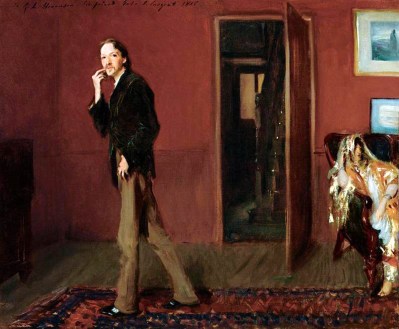

The Duchess of Cambridge, defining a portrait

Poor Kate Middleton. In the royal tradition of artistic and literary representation, what defines her at this moment in time? The creepy feature on her wardrobe statistics in February’s Vogue? Or Paul Emsley’s even creepier official portrait revealed last week? Emsley’s Vaseline lens ‘Gaussian girl’ take on the future consort would have been appropriate had she the complexion of Doris Day, whose preference for the blurred lens was renowned. The fact we all know that Kate’s skin is like butter, her eyes sparkly, and demeanour jollier than her hockey stick makes her first official portrait instantly bewildering. Just imagine, though, if we didn’t know any of those things. Traditionally, we