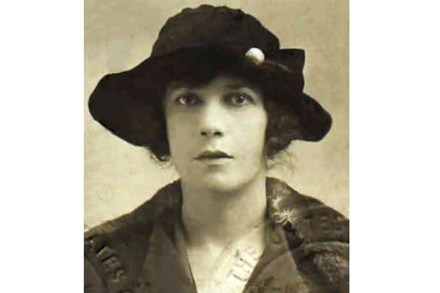

The English lieutenant’s Frenchwoman: the tragic story of Adèle Hugo

In 1882, a sneaky reporter from the Figaro managed to track down Victor Hugo’s only surviving, long-forgotten child to an expensive mental asylum on the edge of Paris. He stalked her as she was being taken for a walk in the local park. She had the ‘profile of a duchess’, ‘staring black eyes’, a perilous hopping gait and odd compulsions. According to the reporter’s inside source, ‘Mme Pinson’ had spent a month removing all the rocks from the asylum’s long driveway and then replaced them one at a time. Thirty-three years later, she could still play the piano and claimed to be writing an opera titled Venus in Exile. She