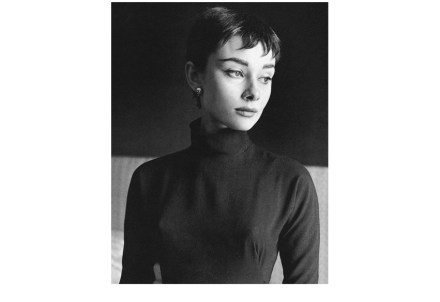

Portraits of an age

By a fine coincidence, two legendary icons of British art were being feted in London on the same evening last month, and both are primarily famous, to the public at least, for their depiction of the Queen. At the National Portrait Gallery, the director Sandy Nairne hosted a dinner to celebrate the portrait oeuvre of Lucian Freud, while the Victoria and Albert Museum opened its major exhibition of Cecil Beaton’s lifetime lensing of Elizabeth II. In the 1950s these two artists were the epitome of London society. Beaton, by way of his groomed exquisite taste and laconic manner, was the epicene idol of sophisticated drawing rooms; the nascent Freud, 30-odd,