All roads lead to Callas

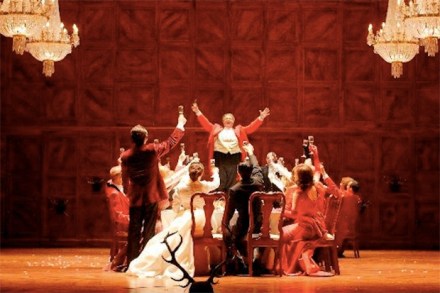

Bellini belongs to that category of not-quite-great operatic composers whose works are also very difficult to perform adequately, and don’t seem to be all that popular when they are. But Welsh National Opera’s theme for the season of Madness means that as one of the leading exponents of operatic insanity Bellini is bound to turn up, and WNO does him proud vocally, if not in production, by mounting I puritani, his last and for some aficionados his finest opera. Norma seems to me to be clearly superior, certainly as drama. I puritani has a wretched libretto, not only linguistically feeble but also with a hopeless plot. It certainly does contain