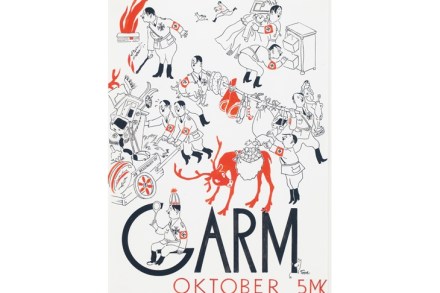

The good, the bad and the ugly | 21 June 2018

Some disasters could not occur in this age of instant communication. The first world war is a case in point: 9.7 million soldiers died, 19,240 British on 1 July, 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, alone. If all that had been seen on social mediaand rolling news threads, public opinion would have shifted immediately. A hundred years ago, however, the sheer awfulness of what was happening took more time to sink in. Aftermath, an exhibition at Tate Britain, deals not so much with the art of the war itself as with the shocked and grieving era that followed the cataclysmic conflict: post-war art. The horrors of