A smart take on literary London: Dead Souls, by Sam Riviere, reviewed

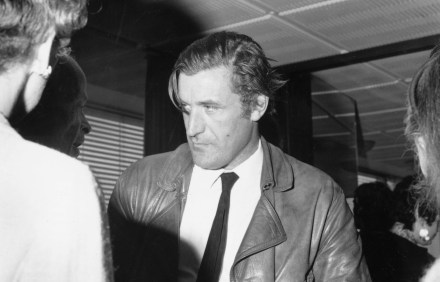

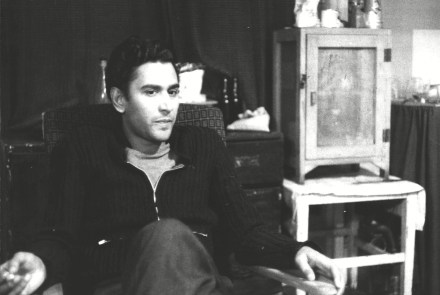

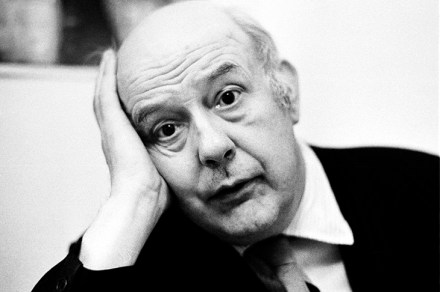

Sam Riviere has established himself as a seriously good poet who doesn’t take himself too seriously: his first collection, 81 Austerities, opened with an account of how he blew all the arts funding money awarded him, and his second, Kim Kardashian’s Marriage, is the only appearance of that august celebrity’s name in the distinguished Faber livery. Now we have his first ‘proper’ novel, following some experimental prose works. ‘Of course,’ as John Cheever wrote, ‘one never asks is it a novel? One asks is it interesting’, and Dead Souls is definitely interesting. It also fits the pattern of the poetry: this is a funny, even silly, but smart take on