The rare gifts of Peter Doig

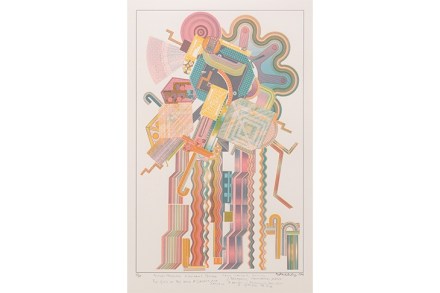

‘My basic intention,’ the late Patrick Caulfield once told me, ‘is to create some attractive place to be, maybe even on the edge of fantasy — warm, glowing, but often, by use, rather seedy.’ He frequently succeeded, as you can see from a beautifully mounted little exhibition at the Waddington Custot Gallery. It is a reminder of what a witty and inventive artist Caulfield (1936–2005) could be. Four screen prints from 1971, ‘Interior: Morning, Noon, Evening and Night’, give a virtuoso display of the visual legerdemain he could work using the simplest of props. These all have the same basic design: a window frame, consisting of thick, black lines, with