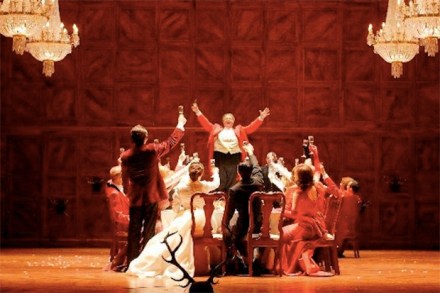

Are theatre audiences getting out of hand?

Laurence Fox has this week joined an increasing band of actors hitting back at misbehaving audience members who seem to forget that they are in public rather than their own living room. He ramped up the drama by launching a foul-mouthed attack on a heckler before storming offstage during a live performance at a London theatre. During the play, The Patriotic Traitor at the Park Theatre, he was heard to say: ‘I won’t bother telling you the story because this cunt in the front row has ruined it for everybody.’ The audience member had been muttering and heckling during the play and apparently became so loud that, for Fox, it was impossible