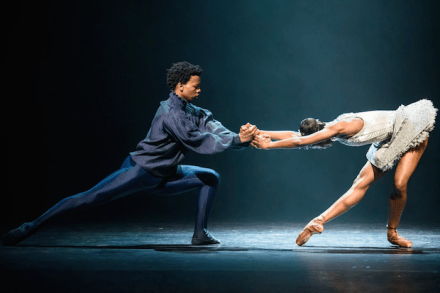

The Bourne identity

From a film about ballet to a ballet about film. In reworking the 1948 Powell and Pressburger classic The Red Shoes for his latest show, Matthew Bourne pays homage to far more than the unforgettable story of a budding ballerina and the bloody toll of her choice between love and career. With the glee of George Lucas recreating second world war dogfights in space, Bourne, a cinéphile since childhood, stuffs his Red Shoes with images from Hollywood’s Golden Age: a French Riviera coast here, a battered old piano there, fur coats and train whistles and sequin-and-feather tap-dancers. The problem with this love letter to cinema is that it blunts the