Ballet’s romantic mantra could be summed up by John Keats’s ballad ‘La Belle Dame sans Merci’, in which a young man remembers his terrible encounter with a supernatural ‘fairy’s child’. Beguiled to sleep with this ravishing fantasy creature, he dreams of a ghostly corps of other chaps similarly beguiled, who warn him that she was a witch who would leave him forever haunted, sick and bereft.

You can remodel this fantasy this way and that, switch the genders, reconfigure death, sleep and hallucination, and come up with Giselle, La Sylphide, Swan Lake, La Bayadère in the 19th century, and then find Fokine, Balanchine and Ashton developing it into the 20th in Les Sylphides, Symphony in C and Ondine. Then the ballet world wakes up to emotional realism and superrational digitalism, attended by kulcha-media denunciation of classical ballet conventions as sexist, racist and old-fashioned.

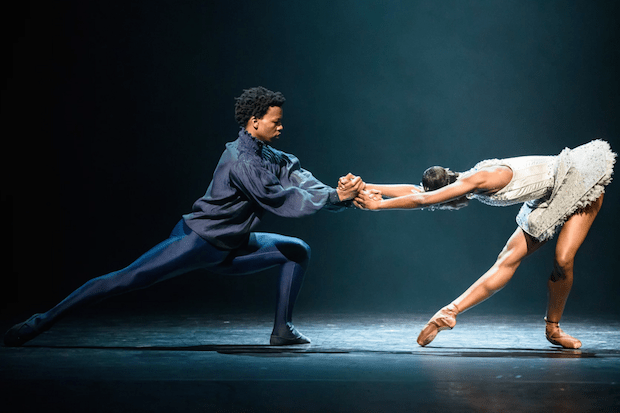

So nothing could have more in-yer-face impact than the resurrection of la belle dame by the hip Arthur Pita in his brilliant little pas de deux, Cristaux, for Ballet Black.

With his Portuguese soul, Pita is unashamed of mystery and magic and can create grand emotional deception with tiny forces, as I regularly seem to say. Here was the romantic trope just as Keats prescribed: the boy feverishly dreaming of a supernatural lovely decked out blindingly in a white tutu sprayed with sequins, to the hypnotic tinkling bells of part three of Steve Reich’s Drumming.

The faerie’s hovering bourrées come straight from the lexicon of phantoms and dying swans. One moment she is stiffly compliant in his arms, the next the pair are quickstepping intimately, and then, suddenly, she switches on the menace. He has the goofy soft face of a dreamer half the time, never looking at her, just imagining her. The piece seemed to me to hit, in miniature, every important base in romantic ballet and modern sexual scepticism.

Did I mention that the dancers, Cira Robinson and Mthuthuzeli November, are black? I should. The company exists, number one, to hire black or Asian ballet dancers, which complicates criticising it.

In Cristaux, does the fact that the dreaming knight and his belle dame are not white-skinned make a difference to it as a work of art? Definitely. Robinson’s stony ebony face and muscular black limbs in all that crystal white make a contrast and fusion of supposed opposites as iconic as a black Santeria Madonna.

And without the presumption of prejudice that a black woman in a white tutu is odd, and without Robinson’s charismatic incarnation of a merciless belle dame, the work would lose both its contemporary challenge and its bold homage to the romantic origins of classical ballet. All that in around ten minutes.

But the rest of last week’s programme misdealt the race card, because they’re not good pieces, let alone potent contributions to Ballet Black’s raison d’être. Christopher Hampson’s Storyville leans questionably on racial clichés with a New Orleans tale of fallen innocents, pimps and oriental madames, melodramatically semaphored rather than choreographed — he seems to have put more passion into compiling his music, a Kurt Weill medley that includes the fabulous Walter Huston singing ‘Lost in the Stars’. The flimsy droops of Christopher Marney’s To Begin, Begin are not worth dancing.

The Royal Ballet’s enthralling production of Giselle might have been designed to express Keats’s ballad, set atmospherically by John Macfarlane in a watercolour autumn forest littered with dead trees and death-pale ghosts. Whatever harsh words I have for the company’s recent commissioning and execution of 20th-century ballet, after two such impeccably stylish and emotionally touching nights as we had last week out in the witchy Rhineland forest, it’s clear that this masterpiece of romantic ballet remains a living treasure at Covent Garden in Peter Wright’s 30-year-old production.

A thrilling partnership has suddenly emerged between Vadim Muntagirov and Marianela Nuñez. Muntagirov, as a lad in English National Ballet, famously found his artistic feet with an older ballerina, Daria Klimentova, and now at Covent Garden seems to have found still more expressive profundity with the senior Nuñez, who has just lost her regular squire Carlos Acosta to retirement.

Muntagirov’s anxious, truly loving young Albrecht drew from her an exceptional portrayal of a happy but fervently superstitious village girl for whom the abyss opens. Both of them have such technical class and stamina that they sustain the eroto-religious mystery of Act 2 to the last note. A pity about the melodramatics of Barry Wordsworth’s conducting and Itziar Mendizabal’s Myrtha, but then we had the splendid side dish of a superb pas de six, a demonstration of Royal Ballet virtues. (When is the extraordinary Yasmine Naghdi going to dance Giselle?)

Next night, plus ça change. Federico Bonelli’s Albrecht strode out with lusty Italian appetite to seduce Lauren Cuthbertson’s pretty village girl quickly before the hunting party caught up with him, but found himself broken by her death and his night of terror in the forest, a changed man without any possible consolation. Keats might have saluted him.

Comments