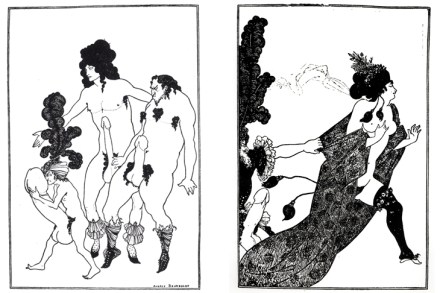

More depravity, please: Salome, at the Royal Opera House, reviewed

The first night of the new season at Covent Garden was cancelled when the solemn news came through. The second opened with a short, respectful speech from Oliver Mears, the director of opera, and a minute’s silence in which the houselights were lowered and we could gaze at the curtains, from which the huge gold-embroidered EIIR cypher had already been removed. For the first time in King Charles’s reign, we sang the national anthem to unfamiliar new words. There were shouts of ‘God Save the King!’And then the lights dimmed once more and we proceeded with the business of the evening, and the life of the Royal Opera. Britain has