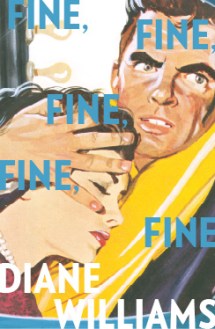

Last Stories

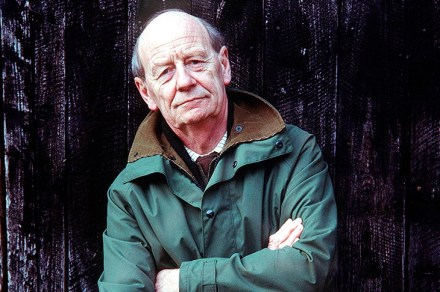

A very prolific and long-standing writer of short stories reveals himself. William Trevor, who died in 2016, owned up to 133 short stories in the two-volume 2009 Collected Stories, and here are ten final ones, written in his last seven years. One shy of a gross, he might have had a character put it. Reading through them, we see occasional echoes and repetitions; characteristic ways of looking at life, and of putting a story together; a slowly emerging political stance; a turn of phrase; some favourite words; a delight in sentences. The novels are splendid. The sequence from The Boarding House to Other People’s Worlds hardly misses a step, and