Hilary Mantel’s fantasy about killing Thatcher is funny. Honest

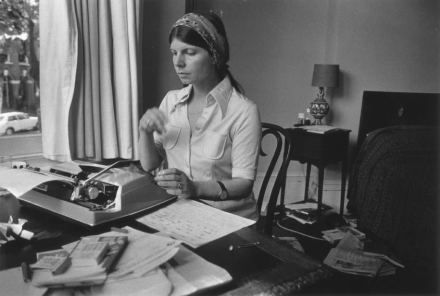

Heaven knows what the millions of purchasers of the Man Booker-winning Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies will make of the ten stories collected here, for they return us to the landscape occupied by Hilary Mantel’s last great contemporary novel, Beyond Black (2005). This, for those of you unfamiliar with her pre- (or rather post-) Tudor work is a world of fraught domestic interiors, twitches on the satirical thread and, above all, stealing over the shimmering Home Counties gardens and the thronged Thames Valley shopping malls, a faint hint of the numinous. Make that a very strong hint of the numinous, for The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher fairly crackles