What Prince Harry gets wrong about therapy

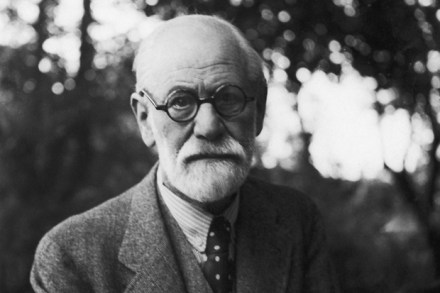

Prince Harry’s endorsement of therapy will likely turn some of us off ever seeking it out. Insisting that therapy has changed him for the better, he is urging his family to partake so that they too can ‘speak his language’ of simultaneously loaded and empty terms – such as ‘authenticity’. ‘If I didn’t know myself, how could members of my family know the real me?’ he said. This non-sequitur subverts the conventional wisdom that sometimes others can know you better than you know yourself. Yet tiring as all the Prince’s interventions are, a peremptory dismissal of psychoanalytic practice would be a mistake. In fact, psychoanalysts would probably refuse to accept the