As gripping as an Agatha Christie thriller: Shooting Hedda Gabler, at the Rose Theatre, reviewed

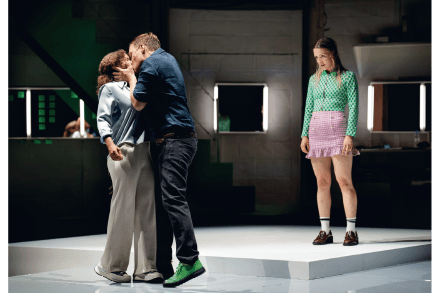

The unlovely Rose Theatre in Kingston is a modest three-storey eyesore. The concrete foyer looks like an exercise area on a North Sea oil platform, and the auditorium itself is a whitewashed rotunda that resembles the chapel in a newly built prison. Yet this cheerless, functional space is perfect for a mischievous new satire, Shooting Hedda Gabler, about recent developments in the acting trade. The central character, Hedda (Antonia Thomas), is a washed-up American starlet who wants to gain artistic credibility by taking the lead in a pretentious film version of Hedda directed by Henrik, a tyrannical Norwegian auteur. ‘There is no script,’ he announces on the opening day. But