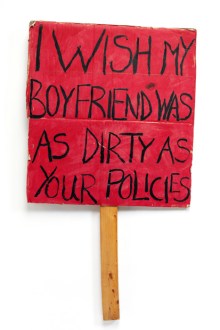

Alexander McQueen may have been a prat but at least he was an interesting one

Alexander McQueen famously claimed to have stitched ‘I am a c***’ into the entoilage of a jacket for Prince Charles. The insult was invisible behind the lining and his tailor master later investigated and found nothing. So what was this? An invention, an embroidery of the truth? It certainly became a good source of publicity as he spread the story — step one in the creation of his bad-boy image. McQueen wore his counterculturalism loudly on his sleeve. Often tediously. He wanted to be dark, dark, oh so dark. Great. I think it’s pratty, but there are millions of people who don’t, so good for him — good for them.