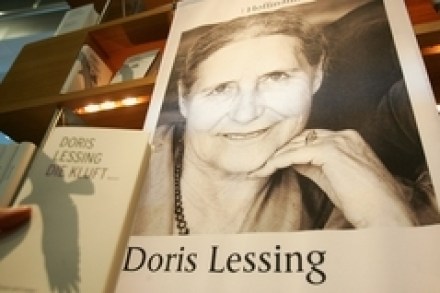

The golden writer

Doris Lessing was last week awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. Philip Hensher traces the career of ‘one of the greatest novelists in English’. Doris Lessing’s Nobel win came as a surprise to everyone, the author apparently included. Despite her enormous, decades-long international reputation, she was less fancied than dozens of patently smaller writers. That