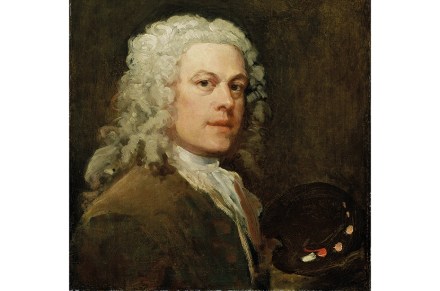

How William Hogarth made Britain

Has any artist ever had a wider impact on the world than Hogarth? He was the motivator behind the most important legislation protecting artists’ copyright, meaning that artists from ordinary backgrounds no longer had to depend on the whims of rich patrons. Like Dickens, he used his art to laugh at and root out abuses