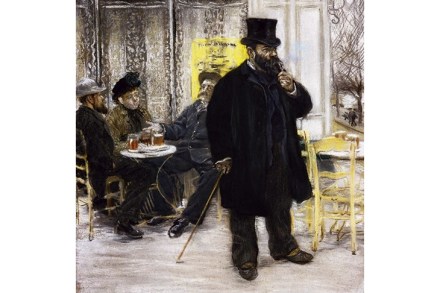

Bohemian bonhomie

Mary Ann Caws, a retired professor of English and French literature at the City University of New York, published her first book in 1966. Since then she has written several dozen studies, many of them about surrealism or modernism; others with such varied subjects as the women of Bloomsbury, Robert Motherwell, Blaise Pascal, Provençal cooking,