Brian Sewell, who died last month, was not popular with his fellow critics. He accused them of kowtowing to power, of puffing up every trendy artist put forward by the galleries and collectors. Of ‘arse-licking’, to be precise (see for example this exchange with Matthew Collings). They could brush off this charge easily enough: Sewell just didn’t get modern art, they said; he hankered for the clear hierarchy of value of the old days. And so he couldn’t really fulfil the function of a critic: to help the public to make sense of the art of our day.

Fair point: he was insufficiently sympathetic to contemporary art. And yet he was also right that most art criticism is excessively sympathetic. It is in the interest of a critic to enthuse about most of what he sees, to seem in touch with it. If the dominant style is showy, inane, ironic, it is in his interest to display a worldly acceptance of this, to smile along, to say, ‘This is simply the sort of art that our era makes, what can you do? Might as well enjoy it.’

Sewell played a valid role as dissenter-critic, blowing raspberries. But he didn’t really help us to know how to value art. He didn’t have a story about what made some modern art great, and why nearly all contemporary art lacks that greatness.

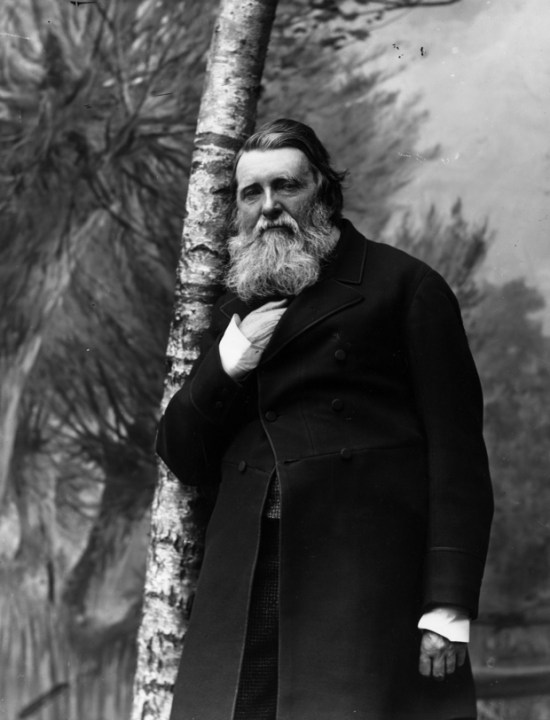

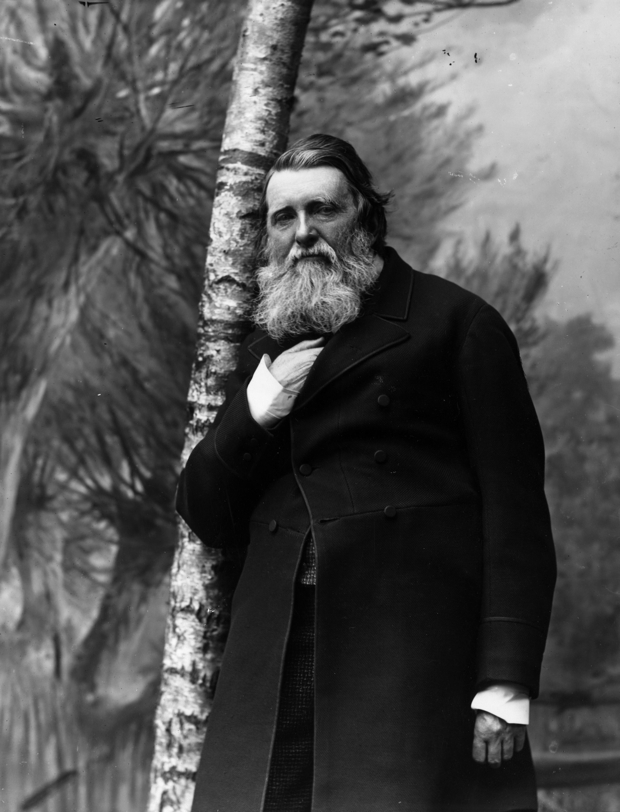

A really interesting critic would share Sewell’s scepticism about the art establishment, but also have a big bold account of what happened in modern art, and what exciting possibilities are present (if not realised) in contemporary art. His or her big bold account would refer beyond art; it would relate art to life. We need a Ruskin.

Comments