Agatha Christie’s The Mousetrap has been running in London theatres for 62 years straight – a period that spans more than 25,000 performances. As is traditional in the genre, it ends with the suspects gathered together for a shocking denouement, during which the detective unmasks the murderer, to general horror. Despite the number of times this has happened, the identity of the killer is apparently ‘the best-kept secret in show business’; at no point has any reviewer felt the need to reveal that the butler did it.

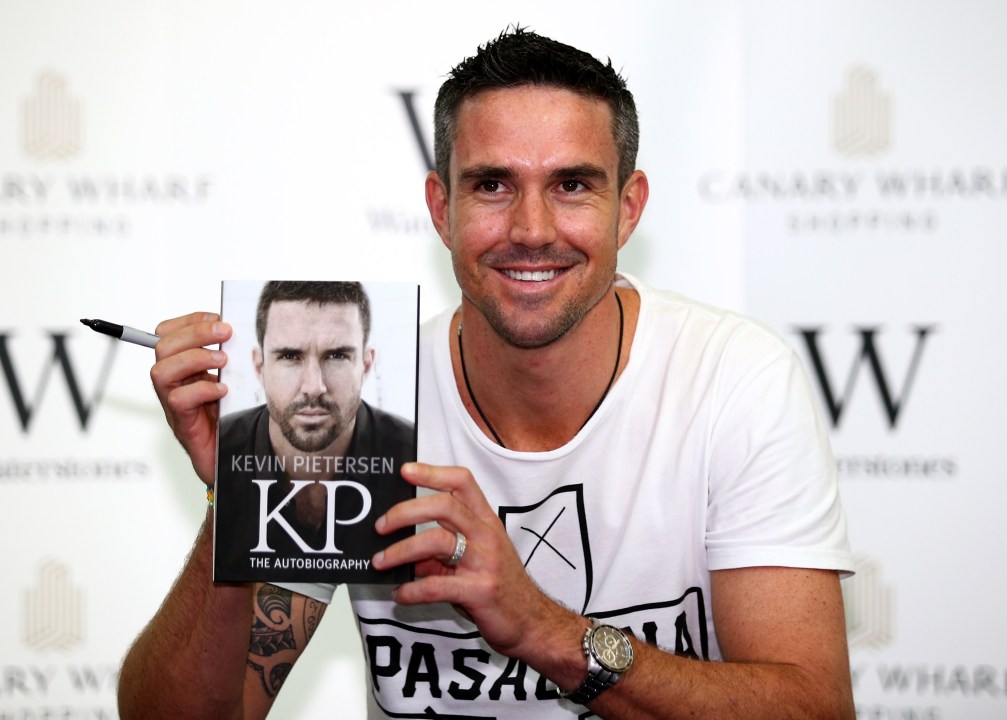

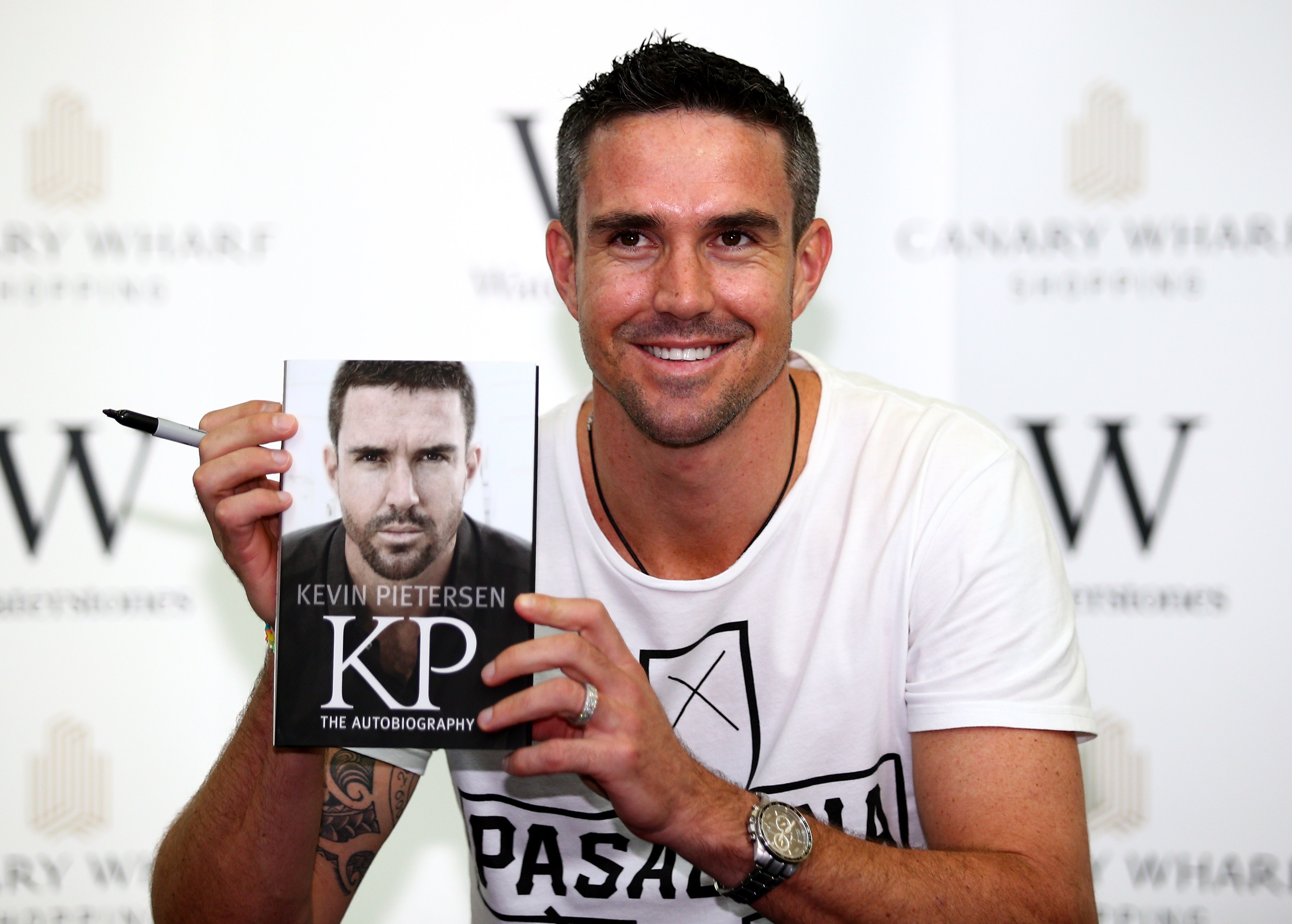

On the other hand, the publication last week of two autobiographies – one by Kevin Pietersen and one by Roy Keane – were treated quite differently. The findings of various speedreaders were consolidated by newspapers into liveblogs, multiple pieces were published revealing the most salacious details, and further digests then compiled – with journalists tweeting their favourite lines. For those unable or unwilling to avoid all media, the books’ contents were entirely unavoidable.

In no other medium is this done. Hell, the bloke who tweets the front pages of first editions even felt obliged to warn of Great British Bake Off final spoilers. And that’s just a bunch of randoms making a few cakes, whereas elite sport obsesses millions.

It is, though, fair to distinguish between the books. Some of what Pietersen had to say relates to matters current in English cricket, which makes it news. Keane, on the other hand, is discussing matters historical; his thoughts have neither use nor purpose beyond our reading pleasure. Nevertheless, his book has been ransacked several days prior to its general availability by those who might demur at, say, the breaking of an embargo.

I understand why. Kevin Pietersen and Roy Keane are two obsessive, thoughtful, compelling and wonderful sportsmen, who’ve played in epochal games and teams. And it’s for precisely that reason that those who actually care about them, and looked forward to the books, aren’t specifically arsed about the rows and revenges. Pietersen’s gripes could have been easily precised in three words: we’re all idiots, while Keane’s antipathy to the human race, and Alex Ferguson in particular, is almost cliché. Rather, those with a proper interest are seeking nuance, detail and knowledge: how to combat Dale Steyn and Mitchell Johnson; how to perform with such startling intensity and consistency.

The distillation of books into ruckus and anecdote is part of a wider problem: much as people like enjoying things, they also like not paying for them. And when it comes to popular culture, it’s usually possible to do both. So, in order to attract the website traffic on which they rely, newspapers – most of which are available for free – describe chunks of a book according to the same rationale: for the benefit of those willing to take an interest but unwilling to invest. And, in particular, that means publishing the rancour-related, because there’s nothing the internet loves more.

Of course, Pietersen, Keane, and their respective publishers know this; their books were prepared with headlines in mind, in the hope that more readers would be drawn in than put off. But, while headlines are hard for newspapers to turn down, it’s unlikely any of them even contemplated announcing details of how the Sopranos ended, because it’s important to protect the pleasure of the consumer. So, with that in mind, how about this: a moratorium on all spoilers, reviews and genuine news stories excepted, for two weeks. And if that sounds unreasonable, well, console yourself that it’s not 62 years.

Daniel Harris is a writer. His most recent book,The Promised Land, tells the story of Manchester United’s treble season.

Comments