Within a few years, and in four books — The Emigrants (1996), The Rings of Saturn (1998), Vertigo (1999) and Austerlitz (2001) — W. G. Sebald achieved a reputation as a major international author. He was tipped for the Nobel, seen to supply heartening proof that ‘greatness in literature is still possible’ (John Banville) and that ‘literary greatness is still possible’ (Susan Sontag).

Literary greatness it seemed, at times, was Sebald, and for a while after the publication of The Rings of Saturn, it was hard to find a work of fictive non-fiction that wasn’t riddled with grainy photographs of dubious quality integrated into the text. Despite Sebald’s sudden death in 2001 his publishing career has continued — and he is now as prolific in death as he was in life, with works including On the Natural History of Destruction (2003), Unrecounted (2004), Campo Santo (2005) as well as two collections of poems, For Years Now (2001) and Across the Land and the Water (2012). This latest posthumous work, A Place in the Country, is a collection of essays on subjects including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Eduard Mörike and Robert Walser, beautifully translated by Jo Catling, a former colleague of Sebald’s at UEA.

Certain words recur in critical appraisals of Sebald: ‘sublime’, ‘ghostly’, ‘melancholy’, ‘lugubrious’ and ‘sui generis’. He is credited with fashioning a ‘new form of the novel,’ a ‘new form of the travelogue’, a ‘new history’ and a ‘new literature’. Such tributes refer to Sebald’s tapestries of seemingly disparate events, his fluid cohesions of the past and present, real and unreal, living and dead. Catling opens her introduction with a telling quotation from Sebald’s essay on Walser:

I have slowly learned to grasp how everything is connected across space and time, the echo of a pistol shot across the Wannsee with the view from a window of the Herisau asylum, Walser’s long walks with my own travels, dates of birth with dates of death…

In his essay on Rousseau, Sebald tells us how he crosses the Lac de Bienne, to reach an island ‘flooded with a trembling pale light’.He discerns the ‘same quality of silence’ as Rousseau must have discerned, ‘a stillness such as is scarcely now to be found anywhere in the orbit of our civilised world, and where nothing moved’. Here, Sebald appears to be the perfect, erudite companion, whispering his anecdotes, interpreting the literary dead. Or, he is a poet-alchemist, scraping around in the depths of the past, transmuting aged murk, base matter, into gold.

This could all get a bit awful, potentially — everything reduced to ‘stillness’, archaic and immobile, like Keats’s Grecian Urn. What rescues Sebald from sonorousness and whittering elegance is that there is something slightly disturbing about his trans-temporal taxonomies and conspiracies of manufactured sense, and he knows it. On Robert Walser, he writes:

What is the significance of these similarities, overlaps and coincidences? Are they rebuses of memory, delusions of the self and of the senses, or rather the schemes and symptoms of an order underlying the chaos of human relationships… which lies beyond our comprehension?

If you find connections everywhere, are you in tune with eternal verities, or a complete fantasist?

His grandfather, Sebald explains, looked just like Robert Walser, and both died in the same year. Later, he describes how Walser adopted the guise of the bourgeois patrician, until he went stark raving mad and ended in an asylum. Bourgeois patricians, the tranquil surfaces of lakes, benevolent guides through European history, are not what they seem.

In another essay, Sebald turns to Eduard Mörike, who tried to create ‘a perfect world in miniature, a still life preserved under a glass dome’. ‘It is impossible to imagine a yet more perfect order. And yet on either side of this apparently eternal calm there lurks the fear of the chaos of time spinning ever more rapidly out of control.’

On the tranquil surface, Sebald plays the sober guide through European history and literature, the Great Works of Greatness. Yet, beneath this calm veneer lies something else, something much more interesting. He crafts compelling metaphors for the lives of others — Walser, for example, as a man who recedes, dissolves — and links these to his own autobiography and the lives of other authors.

It is all so persuasive, apparently authoritative — until Sebald, with a faint smile, hints that all is folly, that he is not escorting us through the ornamental gardens of the past but has hurled us instead into a realm of Borgesian irony, Escher-esque trompe l’oeil. These wilful betrayals and shifts of tone are also reminiscent of Rousseau, who sidles towards the reader in his Confessions and inveigles, charms and perplexes in equal measure. Sebald describes how Rousseau was prone to fits of paranoia, especially when in England. It’s hard not to see this, from a German who spent most of his career in England, as personally subversive as well.

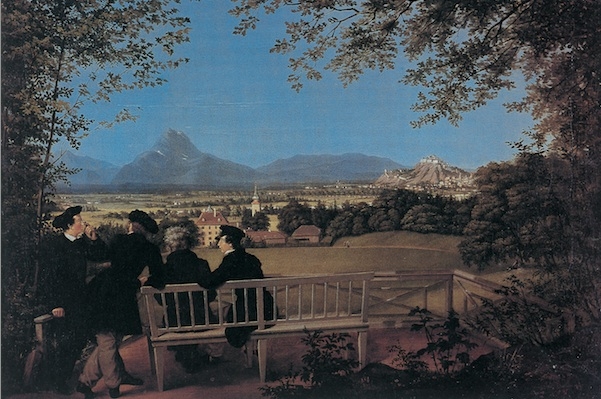

In the last essay, Sebald turns to the paintings of Jan Peter Tripp: ‘The longer I look…the more I realise that beneath the surface illusionism there lurks a terrifying abyss. It is, so to speak, the metaphysical underside of reality, its dark inner lining.’ Of Tripp’s painting of a dog, he writes:

His left (domesticated) eye looks straight at us; the right (untamed) eye has just a shade less light, seems remote and strange. And yet, we feel, it is precisely this eye in shadow which can see right through us.

Is the universe playing a Sebaldian joke? Sebald claims that the shadowy eye of the dog sees ‘right through us,’ and this remark comes itself from the shadows, from a posthumous work — an occult coincidence which he might have enjoyed.

This brilliantly weird and beautiful book ends with the suggestion that everything Sebald wrote about other authors, and artists, he meant about himself, and about the crazy quest for meaning, and how we persist with it, despite the shadows that slide towards us.

Comments