Charlotte Moore’s family have lived at Hancox on the Sussex Weald for well over a century.

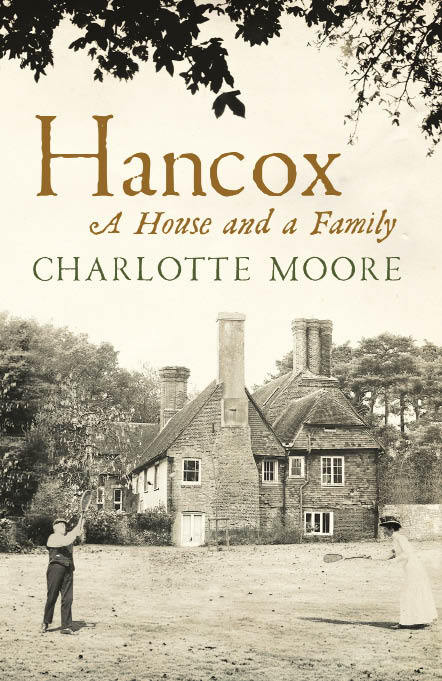

Charlotte Moore’s family have lived at Hancox on the Sussex Weald for well over a century. Hancox is a large, rambling house, and the Moores are a family who throw nothing away. Charlotte Moore still cooks on a 1934 Aga. Every drawer and every cupboard bulges with letters, diaries, receipts, even cheque book stubs. Moore has pieced together this chaotic archive to construct the history of her family. It is a complex but riveting story.

Hancox was bought in the 1891 by a 23-year old spinster named Milicent Ludlow. Both her parents had died, leaving her with independent means. Milicent’s mother, Bella, was a member of the Leigh Smith family, who were descendants of an 18th century banker named William Smith. Though the Leigh Smiths were cousins of Florence Nightingale, they didn’t quite cut it socially. They were illegitimate — the five children of a rich Smith by a working-class woman whom he never married. There was also the worrying matter of the ‘family taint’. Bella Leigh Smith suffered from insanity after the birth of her first child. When her third child was born, she went mad for good. Charlotte Moore discovered the diary of Bella’s husband in a suitcase in the attic, and she uses this to reconstruct in painful detail the story of Bella’s illness. Bella was cared for at home by her husband, and she died of TB aged 42. One of her daughters also grew up to become manic depressive.

The family survived these tragedies partly because they were wealthy. The Leigh Smith brothers didn’t need to work for a living. One brother, Ben, was a Victorian gentleman-explorer who went on five Arctic voyages which he paid for himself: old William Smith must have left a vast amount of money. Crucial to the family dynamic were the aunts. The Leigh Smiths specialised in strong-minded aunts. There was Aunt Anne (Nannie) Leigh Smith, an aesthete and artist who lived in Algiers with her devoted friend Isabella. Today they would be labelled as a lesbian couple but, as Moore wisely says, the Victorians just didn’t ‘go there’. The best aunt in Charlotte Moore’s saga is Barbara Bodichon. Her French husband, Dr Bodichon, a physician with a penchant for nudism, was so weird that no one could understand why she married him (Moore diagnoses high-functioning Autism). Barbara was fat, outspoken, bossy, feminist and kind. Childless herself, she took a mothering interest in the younger generation. It was Barbara who spotted the talent of the junior doctor, Norman Moore.

Norman Moore was a remarkable man. His philandering Irish father absconded when he was a baby, and he was brought up in straightened cirx by his iron-willed mother. He was very bright, super-energetic and surprisingly nice. He had a knack of attaching himself to generous patrons. Barbara Bodichon took him up when he was a star young medic with a social conscience at St Bartholomew’s Hospital. Soon Norman fell in love with one of Barbara’s nieces, the beautiful, fragile Amy. The snobbish members of the Leigh Smith family disapproved and insisted on a separation, which naturally had the effect of making true love stronger. Norman Moore filled eleven volumes with unsent letters to Amy. At length, Amy’s family relented, but shortly after the marriage she showed signs of TB.

After Amy’s death from TB — harrowingly described by Charlotte Moore — Norman married her first cousin Milicent. They went to live at Milicent’s house, Hancox. But the family’s troubles were by no means over. Far from living happily ever after, Norman and Milicent found themselves plunged into a new, 20th century sort of saga. Not only did Norman’s children revolt against their new stepmother. But Norman himself fell in love aged 60-something with Milicent’s best friend, a woman named Ethel Portal. Their passionate letters show that Norman had at last found his soul mate, but there was no question of divorce, and the Moores lived uneasily in a kind of ménage a trios. And then, in 1914, Norman’s youngest son was killed aged 20, fighting in France. Norman never recovered.

Charlotte Moore has a novelist’s sense of plot. She handles her large cast of characters deftly, weaving a skilful narrative out of the archive that fills her house. This saga of upper-middle class English life negotiates the social territory of Trollope and Galsworthy, but Charlotte Moore has a very 21st century take on it. Unsentimental, witty and humane, she explores the secrets and the silences of family life – the madness and the illness – in a way that is utterly compelling. This is a marvellous book.

Comments